It’s 1984 or 1985, Prince and the Revolution are in California, and they decide to drive out to Joni Mitchell’s house in Malibu for dinner. All devotees—Prince says his favorite album ever is 1975’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns—they chat and admire her paintings, and then Prince wanders to the piano and starts teasing out some chords. “Joni says, ‘Oh wow! That’s really pretty. What song are you playing?’” as band member Wendy Melvoin later recalls. “We all yelled, ‘It’s your song!’” Prince will perform his gorgeous arrangement of Mitchell’s “A Case of You” in concerts up to the final month of his life.

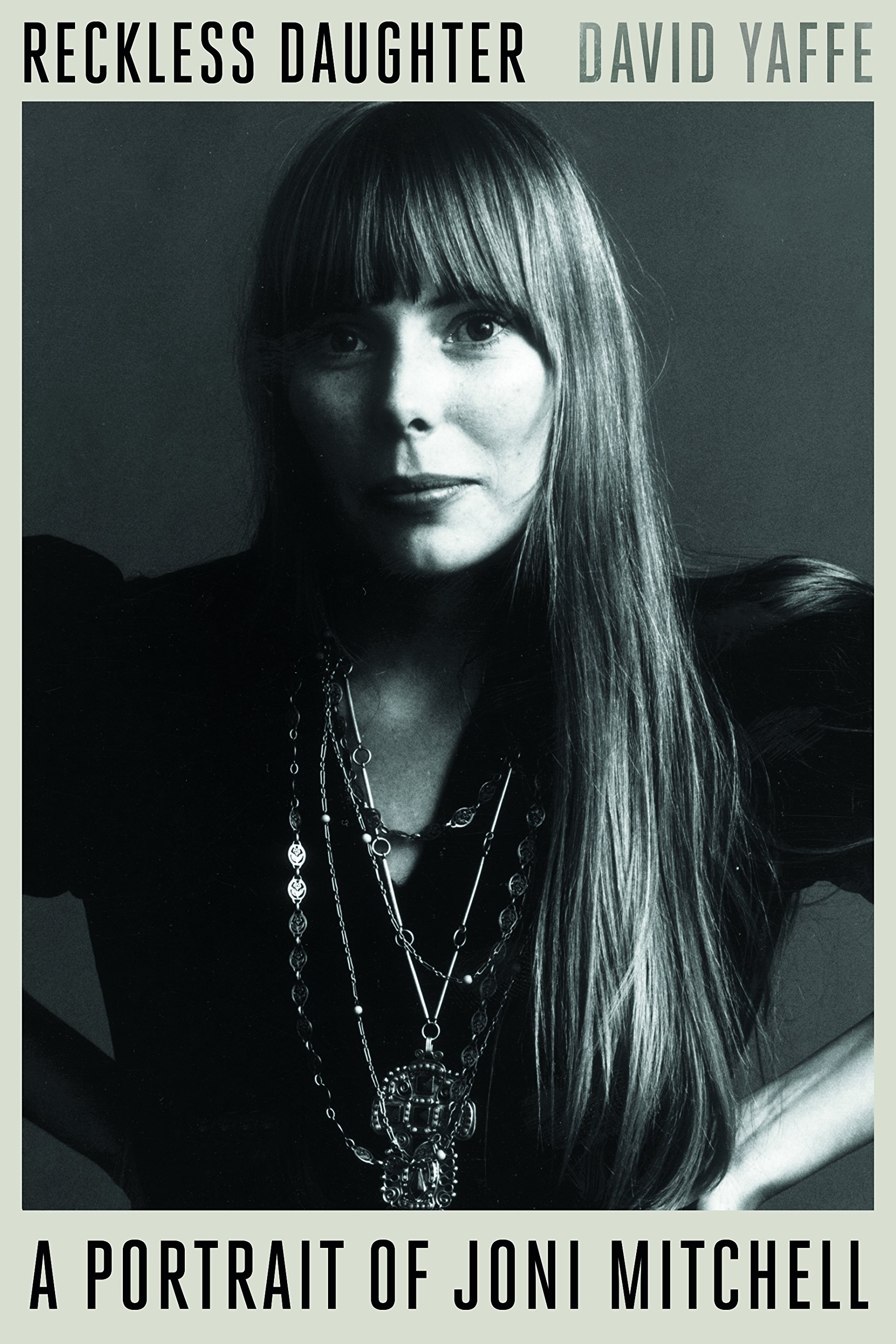

This anecdote from David Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell is rare for being sweet and funny, not sad or rancorous. It’s endearingly humbling, while still hinting at her ample ego: She really does love her own stuff, even when she doesn’t know it’s hers. And why shouldn’t she? For more than a decade, the singer from Saskatchewan bounded from masterpiece to masterpiece, her second-string songs superior to almost anyone else’s best. Yet, among her generation’s legends, she is the most persistently sidelined.

Mitchell is easy to pigeonhole as that “poetic, confessional female singer-songwriter,” provided you overlook half her work and the fact that, before her, there really was no such thing. Even on her earliest, overly demure albums, she’d taken Bob Dylan’s cue that pop songs could say anything (she often named “Positively Fourth Street” as her bat signal) and was using it to dismantle the pedestal she was placed on: The ingenue was gazing back and seeing through her watchers, keeping charts of power plays in a fine calligraphic hand. The girl all the pop songs were about was stepping up to tell them what they got wrong.

She shared with her Canadian compatriots Neil Young and Leonard Cohen the distanced perspective that gave their voices a stark autonomy. (As Margaret Atwood once said in a tribute to Mitchell, in their day you were told you were a lunatic if you thought you could be an artist in Canada.) But because she couldn’t be one of the boys like her pal Neil or a keeper of the poetic patrimony like her onetime paramour Leonard, she built her own distinct lexicon, part journal and sketchbook jottings, part intimate conversation, part wry postwar fiction, and part barroom jive. In 1971, Blue (which includes “A Case of You,” a song about Cohen, as it happens) kicked off a six- or seven-album streak that stands beside Stevie Wonder’s of the same time or Dylan’s mid-’60s run. Each record was unlike the last, each with fresh aesthetic propositions to test, each ready to die trying. Listen to the right one at the right time in your life, and you feel like a doctor just handed you an ultrasound of your soul.

Mitchell excelled at channeling the subconscious of her time, especially as it was negotiated between men and women, but she was also always trying to get outside that orbit. She didn’t want to be a case of anything, except herself. The very chords she played were unique, belonging to no tradition except the one she generated with her own tuning system. She’s called them her “chords of inquiry—they have a question mark in them.” It wasn’t until she began working with jazz musicians that she found a band that could follow her (the rock dudes were hopeless). Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter took her as a musical peer. With rare exceptions, she refused to let anyone else—that is, any man—produce her albums, making her a pioneer in the studio too. No wonder Prince identified.

Though Mitchell benefited from a brief revival during the Lilith Fair era of the ’90s (amplified by the story of her reconnection then with her long-lost daughter), lately young musicians have been genuflecting to Fleetwood Mac’s Stevie Nicks instead as the godmother of uncompromising female self-expression in rock and pop. Maybe citing Mitchell feels too clichéd: She was never too big to fail, but she’s too big to be cool. Or it might be that her reputation, as always, is still saddled with an invisible asterisk. At first, the asterisk meant “(for a girl),” as witness the mixed awe, sexualization, and condescension documented in Joni: The Anthology, a new collection of interviews and articles over the decades, edited by Barney Hoskyns. Salacious gossip about whether this song was about James Taylor or that one about Graham Nash overshadowed her art. Later, the asterisk came to mean “(but why’d she do all that weird stuff?).” Her later-’70s turn to her version of jazz disappointed and even angered the critics and fans she’d won with Blue and Court and Spark (her only real chart hit). Most recently the asterisk has meant “(but what a crank!).” Decades of being patronized, ogled, judged, and confined led to repeated retreats from the business. Mitchell got paranoid and arrogant in interviews, firing curt insults at her peers and younger artists. The bitterness leaked into her music too, which from the ’80s on was weighed down by a tendency to lecture and shake her fist at clouds (the ones she was once wise enough to say she really didn’t know at all).

Of course, Dylan hasn’t been his own best advocate over the years either, but a woman isn’t granted the same leeway for uncooperative behavior. She saw it coming before she was thirty: In a 1971 Rolling Stone profile included in Hoskyns’s anthology, she says, “I’ve changed a lot. I’m getting very defensive. . . . I feel like I’m going to be an ornery old lady.” Today, at seventy-three, Mitchell, after a minor renaissance in her mid-sixties, is still in recovery from a near-fatal 2015 brain aneurysm, and it’s uncertain if she’ll ever work again. This may be the last chance the world has to abandon all caveats and show Mitchell her due, instead of waiting for the obituaries.

While shelves buckle with Beatles and Dylan studies, and Young and Cohen have gotten solid book-length treatments, the few books on Mitchell have been limited, either too hagiographic or subsuming her under second-wave feminism or California lifestyle-ism. Yaffe, a veteran music journalist and English professor at Syracuse University, has better intentions. Reckless Daughter is thoroughly researched, with original interviews with Mitchell as well as friends and collaborators across her life span. But its flaws in craft, tone, and focus leave it short of definitive, and a little maddening to read.

The book is at its best on Roberta Joan Anderson’s childhood in repressive, rural, postwar Saskatchewan, and her life-altering experience of being bedridden by polio and quarantined for long, lonely months at age ten. It captures her extroverted teen years (indifferent to books, going out dancing whenever she could), and the turning point that came when she got pregnant during her first year of art school, took off to Toronto to keep it from her conservative parents, and gave up the child for adoption. It was then that the aspiring painter decided to start taking her musical hobby seriously, Yaffe tells us, but he skimps on how she went about it. A passage from Nicholas Jennings’s book on that era in Canadian music, Before the Gold Rush, found in Hoskyns’s anthology, does a better job of capturing her early years in the clubs and folk festivals, intriguing observers one week and amazing them the next. Reckless Daughter often loops and shuffles chronology in confusing ways,

failing to set up important anecdotes or figures (such as her business partner and onetime roommate David Geffen, the subject of “Free Man in Paris”). Meanwhile, it belabors its motifs and themes, in ways that are either pompous or disorganized. By page 250, I swore that if Yaffe used Mitchell’s famous “Woodstock” lyric one more time to sum a situation up by saying how near or far she was from getting “back to the garden,” I would drown the book with a watering can. On the songs themselves, Yaffe is adequate, but linear and teacherly.

He also buys in too much to Mitchell’s own rearview demonizations of her relationships, instead of maintaining a broader perspective on the ways she repeatedly felt compelled, as an extraordinary woman caught in a sexist society, to flee rather than limit herself for any man. From the ’80s forward, her propensity for feuds and conspiracy theories becomes exhausting to follow—no biographer could really avoid that, but Yaffe doesn’t do enough to try. He also never quite grapples with Mitchell’s muddled take on race: Though she has a sizable black fan base (witness Prince, again) and socialized and worked with black musicians more than most of her cohort (part of the backlash against her jazz period was certainly racial), she was often crassly self-congratulatory about it. She appeared on the cover of 1977’s Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter in pimp drag and blackface, and even went to parties disguised as “a brother,” as she put it. I think we Canadians often naively exempt ourselves from American racism and underestimate its intense fallout, but Mitchell’s projection of her own feelings of otherness onto black men verged on fetishistic.

Nevertheless, Reckless Daughter does encompass the sweep of Mitchell’s complicated life. It left me with a fuller sense of her creative process and her relationships with her collaborators. For now it’s the strongest account we have. One problem for writers may be that unlike the work of Dylan or the Beatles, which was full of disguise and mystique and offered critics a surfeit to speculate about, Mitchell’s art was staked on a radical honesty, no matter how enhanced by metaphor. It radiated self-sufficiency. The question isn’t so much what her music meant but how she did it, and looking more closely at her life only makes it more inexplicable. How can we grasp what it was like to be Picasso (to use one of Mitchell’s own favorite comparisons) but born female in the remote northern prairies in 1943? Even considering the postwar boom and the expansiveness of the age, there’s no adequate way to account for the imagination and willpower it took to come out of nowhere, basically unschooled, overcome her era’s low expectations and contemptuous judgments of pretty young women, and become this singular, indispensable, and, yes, ornery chronicler of heart and mind.

It is easier to understand that all that internal pressure and external resistance gradually bent her out of shape. Even then, she kept trying to grow. On finishing Reckless Daughter, I was left wondering if this was mainly a happy story or a sad one. There’s probably no answer, or at least Mitchell isn’t likely to provide it. All I know is that for those of us who’ve been blessed to listen, it was, as she once sang, just like Jericho: The walls came tumbling down.

Toronto-based writer Carl Wilson is the music critic for Slate and the author of Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste (Bloomsbury, 2014).