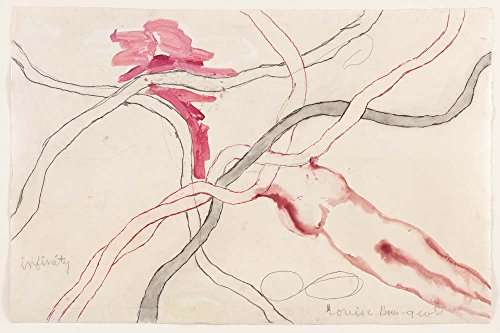

DURING A CAREER of more than seventy years, Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) was a consummate insider. For most of that time, she was hardly recognized outside the small circle of the New York art world. That abruptly changed in 1982, when curator Deborah Wye organized a Bourgeois retrospective at MoMA, only the institution’s second devoted to a living woman sculptor or painter. Sculpture suited Bourgeois: Its often-obdurate materials provided a productive counterweight to her forceful creative psyche. But early and late in her career—at first constrained by space, time, and resources, and later by age and infirmity—she embraced the physically less demanding media of drawing and printmaking.

Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait, Wye’s book accompanying an exhibition this fall, aims to illuminate the artist’s entire career through careful attention to her printmaking. While sculpture naturally obscures the stages of its conception and creation, drawings and prints tell the story of their making, offering an unparalleled window into the artist’s thinking and process. Juxtaposing print sequences with drawings and sculptures related to them, formally or thematically, Wye argues that the prints are essential for evaluating Bourgeois’s overall achievement. This is certainly true, but Wye goes a step further: Bourgeois, she observes, “constantly revisited the themes and forms of her art, in all mediums, as she sought to grapple with the troubling emotions that motivated her.” Here, Wye risks putting the artist’s troubled mind, rather than her art, center stage. An output whose effectiveness as art had dramatic ups and downs is given a pass as simply emotional expression.

Nevertheless, Wye’s volume offers valuable insights into Bourgeois’s thought. Wye is right to note that seeing the evolution of proofs “is akin to looking over Bourgeois’s shoulder as she worked.” For example, the book presents two versions of Sainte Sébastienne, 1990–94, in ten states and variants across three spreads, capturing multiple facets of Bourgeois’s artistic personality—vanity, affection, a sense of victimhood, anger, and determination. The feminized martyr’s flowing hair identifies her with Bourgeois, who was so proud of her own. Smiling as the arrows strike her, she evolves from a top-heavy striding figure with a feline double to a figure covered in monograms to a headless torso that has a striking sculptural quality. During her last decade, the artist, who seemingly discarded nothing from her past, created sculptures from old clothing and printed on scraps of cloth. A touching masterwork of this period is the thirty-five-page book Ode à l’Oubli (Ode to Forgetting), 2002, whose pages are old linen hand towels adorned with fabric collages. Editioned in 2004 with digitally printed images, the work retains a handmade quality. Nestled among designs in softly faded colors are phrases—such as “I had a flashback of something that never existed”—that evoke a painful but cherished history.