Andre Agassi’s Open was a groundbreaking memoir for a tennis player when it came out in 2009. The writing had verve and pop, as Agassi (and ghostwriter J. R. Moehringer) opted to tell his odyssey in the present tense, as if reliving every drama. And the confessionals along the way felt truly revealing. Agassi presented himself as a lost man: “I open my eyes and don’t know where I am or who I am,” reads the first line, bringing to mind a tennis-pro Gregor Samsa. We follow him from an intimate vantage point: crying in the shower, enduring militant training sessions with his father, dallying with performance enhancers and other drugs, and wearing a ridiculous (yet iconic) wig during Grand Slam matches.

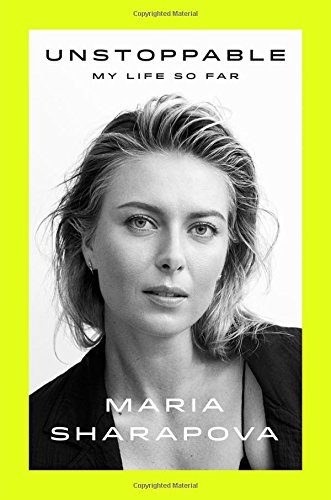

Open is unique because a tennis player’s life typically doesn’t have much arc, or at least much unpredictable arc. Tennis is a game of mental and physical control. To execute the consistency that leads to Grand Slam championships requires a kind of monkish discipline that’s at odds with spontaneity and introspection. While many of the greats on tour have released memoirs or versions of them, like Andy Murray and Rafael Nadal, there’s a predictability at play: The stories start with the domineering tennis parent, the lack of childhood; the players find themselves amid success, struggle to hold on to that success, and eventually fret about their legacy. In Unstoppable, Maria Sharapova recounts a similar story: a determined journey from the bitter cold and desolation of Siberia to the warm (at times burning) glow of international superstardom.

Sharapova first made a name for herself on the tour as a teenage wunderkind who intimidated her opponents with her violent, shrieking style of play. “Even then, I tried to set myself apart,” she writes about her game in the juniors. “No emotion. No fear. Like ice.” She isolated herself from other players and refrained from making friends in the locker room. This was all part of a larger strategy. “I was grunting when I hit the ball,” she writes. “I was developing the persona that would become such an important part of my game.” This persona, which she calls her “biggest edge,” was forged with the help of one of the tennis memoir’s archetypal looming figures: the tennis parent. Growing up in Siberia and in the shadow of Chernobyl, Sharapova started practicing the sport as a young child with her demanding father, Yuri, who advocated a Soviet sense of stoicism. Winning was what mattered. Weakness was not allowed. These were among his lessons, she writes, delivered morning, day, night.

“The tennis parent is the will of the player before the player has formed a will of her own,” Sharapova writes, raising a question familiar to many tennis memoirs: Do dreams of greatness form in the child, or is the idea of winning mostly tangled up in the pursuit of parental love and acceptance? Sharapova describes her father with humble adoration. She understands why he pushed her so hard. He wanted to be a pro skier and cyclist, but when those aspirations failed to materialize, he found a way to maintain his competitive spirit through his daughter.

While others may mourn a lack of normalcy or a missed childhood, the dream he hatched and she executed brought them closer together—so close that, early on, they developed a language that did not require words, a Zen state in which coach and pupil communicated through the game. “A lot of the time it was just about being across from each other, thinking the same thing, which was nothing,” she writes. “That’s about as close as you can get to another person.” Yuri Sharapova has been a controversial figure in his daughter’s corner, and a constant source of drama with her coaches. But for her, it was all part of growing up. “Yuri struck many people as a typical crazy Russian father, hypercontrolling and iron-willed,” Sharapova writes. “This was not true, or not entirely true. . . .Yes, my father did pace on the sidelines. He did whisper in my ear. . . . He did sit in the stands, giving me signals, which pissed off everyone.” Yet to Sharapova this was all entirely necessary. “Without those parents, you would not have the Williams sisters or Andre Agassi or me.”

While writing the book, Sharapova consulted her own diaries. She interviewed early mentors (like the elusive California guru Robert Lansdorp), the agent who turned her into a megabrand (Max Eisenbud), self-promoters (not too much love for Nick Bollettieri). All the big matches are relived in a speedy, engaging way, and her prose exudes confidence as she describes her ability to dominate her peers on the tour and how she came to be considered one of the greatest female players of the game. Her writing becomes more vulnerable, frustrated, and interesting when she explores her struggles with Serena Williams. In the twenty-one times they’ve faced off against each other as pros, Sharapova has beaten Williams only twice, both times in 2004, when Sharapova was still seventeen and upset Williams to win the finals at Wimbledon. “Even now, she can make me feel like a little girl,” Sharapova writes of Williams. “She looks across the net with something like disdain,” like she is “the only person that counts. And you? You are a speedbump. You are zero.” Sharapova speculates that Williams will always loathe her, in part because she saw Williams bawling after Sharapova beat her in 2004. “I think she hated me for seeing her at her lowest moment,” she writes. “But mostly I think she hated me for hearing her cry.” Sharapova doesn’t fret about the animus. For her, hatred is an asset—an emotion to summon and harness—and perhaps her final hope for victory: “Only when you have that intense antagonism can you find the proper strength to finish her off.”

Sharapova is at her best when she is calculating, but where do the calculations end? Unstoppable itself appears to be part of the athlete’s plan to control her image, to stare down the reader. In a sense she plays tennis parent to her own persona, keeping it focused entirely on victory. As she notes, she timed the book’s release to coincide with her retirement—which she intended to announce at this year’s US Open—an easy hook for sales.

But things have not gone according to plan. In early 2016, at the Australian Open, Sharapova failed a drug test for meldonium, a substance that had just been placed on the International Tennis Federation’s banned list. While others would have simply denied it or issued a statement about confusion over the new rules, Sharapova called her own press conference. She wanted to beat the news and tell the story in her own words. The press conference was an albatross, generating more headlines and snippy comments from fellow players than Sharapova could have imagined. In a way, all the training her father gave her as a child to feel hatred and anger for her opponents, and all her efforts to maintain her cold veneer on tour, was working against her. It’s hard to be liked after building a career on a commitment to disdain. The Sharapova method had backfired. She was officially suspended from playing for two years, a catastrophic setback at her age (she’s now thirty). Ultimately, she appealed the ruling, which was shortened. But the damage remained.

She seems to be treating the suspension much like she has treated her other challenges—as an opportunity to summon a new burst of motivation. She’s currently on the circuit of smaller tournaments, hoping to work her way into the Grand Slams where she was a staple for more than a decade. Here, we return to the anger and the chilly persona that helped make her a star in the first place. “I assume, when I stop playing, that everyone will be able to forgive me and that I will be able to forgive everyone,” she writes, suggesting that she sees, in retirement, something beyond me vs. them, the typical dyad of the tennis memoir. But as Unstoppable suggests, Sharapova remains the player who was created to operate “like ice,” and until she leaves pro tennis it’s likely that her arc and her motives won’t change. She won’t be able to reflect much on herself or others until she walks away from pro tennis: “As long as I am in the game, I need that intensity.”

Geoffrey Gray is the author of Skyjack: The Hunt for D. B. Cooper (Crown, 2011) and the founder of the magazine True.Ink.