Around a decade ago, future Obama White House speechwriter David Litt was a contented Ivy League slacker. The breed probably sounds oxymoronic to many Americans, but where do you think the CIA got its most imaginative recruits in the 1950s? Funnily enough, it’s also where postmodern TV comedy shows get their savviest writers today.

Litt’s story suggests that’s no coincidence at all. By his senior year at Yale, he’d not only interned at The Onion—his idea of nirvana until too few of his gags made the cut—but also applied for a job with the Agency, which went nowhere even faster. He wound up combining those career paths after he idly tuned his seat-back TV to an Obama campaign rally in Iowa while he was flying into New York in early 2008. Out of the blue, his life got changed by “a two-inch-tall guy.”

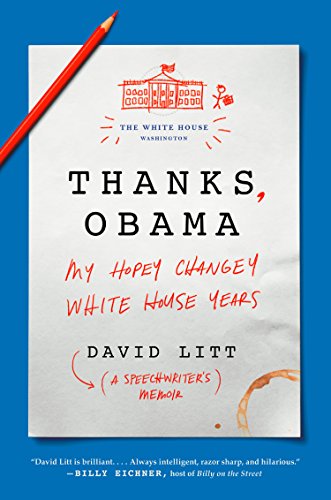

That’s just one of dozens of droll lines in Litt’s Thanks, Obama: My Hopey, Changey White House Years (Ecco, $28), which could be the funniest White House memoir you’ll ever read. Christopher Buckley—his nearest competitor—doesn’t count. Buckley turned his experience as a speechwriter for then Vice President George H. W. Bush into fiction instead.

One of Litt’s advantages is that he wasn’t a policy guy. (The distinction he makes between adrenaline-driven “campaign people” and wonky “policy people” is one every political junkie will recognize.) Probably the weightiest Oval Office decision he was ever involved in was whether to include a “presidential dick joke”—“Dreams aren’t the only thing I got from my father,” ultimately vetoed by potus—in Obama’s routine at the 2012 White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. It was a long time before Litt felt confident the president even knew his name.

A confirmed “Obamabot” by the time his flight landed at JFK, he served as a campaign organizer in Ohio, quickly graduating from unpaid volunteer to underpaid staffer. But after Election Day, he almost vanished in the shoals of Obama ’08 alums hoping for summonses to serve the new administration. Checking in with his similarly stranded campaign coworkers, Litt writes, “was like reading logs from an Arctic expedition as it slowly realizes it’s doomed.”

Only after the 2010 midterms did he get a job as a speechwriter for senior White House adviser Valerie Jarrett, which eventually led to becoming “the White House’s token funny person” writing for POTUS himself. From then on, cooking up jokes for the WHCA dinner was Litt’s annual equivalent of crafting the State of the Union address, and apparently very nearly as high-pressure a showcase. By his second year at the task, he had to buy a mouth guard because he was grinding his teeth in his sleep.

Litt’s sessions with Obama obviously had a different agenda than, say, the decision to take out Osama bin Laden. Unless Monica Lewinsky was a rabid Rue McClanahan fan, he may be the only person ever to sing the theme from The Golden Girls in the Oval Office for POTUS’s enlightenment. For just that reason, his take on Obama’s personality and temperament has some interesting wrinkles. Obama’s “ordinary laugh,” we’re told, was “a self-aware one that was an act of judgment as much as reflex.” Litt saw him genuinely dissolve into hilarity just once—as if, however briefly, he’d forgotten “which person was the president.”

Elsewhere, we get glimpses of the backstage cockiness Obama took pains to keep out of public view. Dismissing any need for a final run-through of one WHCA speech, he says, “The truth is, I’m pretty fucking good at this.” He was, and the book also provides some nicely monitored close-up views of Obama’s gradations of impatience when other people aren’t. One big-picture observation sure to enrage Clintonistas and delight Republicans is, “Where Clinton’s ego expressed itself in an insatiable craving for power, Obama’s expressed itself in the absolute conviction he deserved it.” It’s difficult to agree with the author’s peculiar contention that this made Obama “authentic,” since that brand of egotism was precisely the quality he had to conceal.

Litt is at his most attractive when he indulges his readers’ craving for inside dope on all the stupid, menial details of everyday life inside the ultimate power bubble. You know, the stuff more solemn presidential memoirs omit, including the chipper assurance that “Air Force One is exactly as cool as you would expect,” and the lowdown on how 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue’s reality stacks up against The West Wing. (Answer: not too well, although the real-life lingo can be even more gnomic than Aaron Sorkin’s dialogue.) He even lovingly describes his favorite and least favorite men’s rooms in the White House—the sort of Homeric catalogue you can imagine winning James Joyce’s (and Beavis and Butt-Head’s) approval.

Yet there’s a more reflective, occasionally poignant story being told here as well. Litt is a first-rate, self-deprecating cutup, but he didn’t fall in love with Obama in 2008 because he dreamed of writing presidential one-liners. He was a hope-and-change true believer. More vividly than someone higher up in the food chain could, Litt conveys the whole cycle of hero-worshipping political commitment, with early fervor followed by ambition’s sneaky arrival through a side door. Next comes delight in insider perks, increasing responsibilities, increasing stress, bunker-mentality gloom whenever things go south for the administration, and perseverance running neck and neck with burnout.

Tellingly, whenever Litt did get assigned a policy speech, he crammed it with nuts-and-bolts specifics sure to knock specialists’ socks off and bore everyone else witless. But his boss invariably knew better, ultimately teaching Litt a lesson that sounds antediluvian in the age of Trump: “For the president . . . every speech is a speech about America.” If that includes good WHCA jokes, so much the better for the country.

Tom Carson is a freelance critic and the author of the novels Gilligan’s Wake (Picador, 2003) and Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter (Paycock, 2011).