Take it from hedge funder Florian Homm, now a witty fugitive who appears in Lauren Greenfield’s Generation Wealth (Phaidon, $75) hanging out with his bounty hunter pal and his bodyguard: “What you’re sold in this world is a bag of rotten goods. The striving for more and bigger will never, ever lead you to the right place. All of us are following a dream, a toxic dream.”

This sentiment resounds throughout the book from a global chorus of mavens and native informants. Old money to new, we hear from haves, have-nots, wanna-haves, and used-to-haves from Los Angeles to Newport, Rhode Island; Moscow to Dubai. (Greenfield’s itinerary alone would take up this whole page.) While there are a happy few bubble dwellers, Greenfield tells a familiar tale. Thanks to the predations of unfettered capitalism, the American dream has become a nightmare—one that might be our leading export. Spanning thirty years of the photographer’s work and oozing juicy detail, this hefty compendium of consumer culture and status anxiety is hard to sum up. It is as exhaustive and eye-catching as human folly itself.

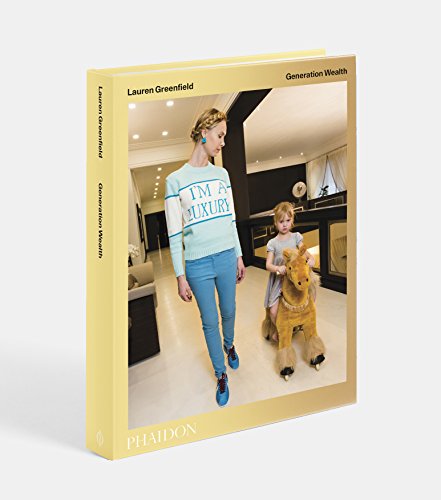

Greenfield has long chronicled consumerism and its poison pedagogy in books such as Fast Forward (1997) and Girl Culture (2002) and docs like The Queen of Versailles (2012). With able curator and editor Trudy Wilner Stack, Greenfield sifted through over half a million images, making Generation Wealth a sweeping retrospective. Each section opens with a half-page primer on the credos of wealth—“I Shop Therefore I Am,” “New Aging,” “Sexual Capital,” “The Cult of Celebrity,” etc. A hoard of Greenfield’s glossy but gently ironic portraits and candid shots, interspersed with deadpan captions and illuminating interviews, depict the global trance that has replaced traditional values with the cult of bucks. Greenfield covers each species in the capitalist food chain: from top-predator oligarchs and fraudsters to schlimazels burned by the 2008 crash; from Elon Musk’s “starter wife” to Nevada “ho-fessionals,” “Bling Dynasty” yachters, “Limo Bob,” and Russian debutantes waltzing at events where luxury brands wield the prestige formerly enjoyed by royals, Lenin, and Stalin.With striking candor, Greenfield’s subjects—including rapper G-Mo, auteur of the video for “Ballin’,” and the spendy Siegels of The Queen of Versailles—divulge how money and class have shaped their lives and their hides. Voilà, our deeply superficial culture: a spectacle where image and money are confused with identity and self-worth. Buying into this worldview is a losing proposition. And apparently it’s irresistible.

In age-inappropriate makeup and a blond bouffant coiffure, six-year-old pageant winner Eden eyes Greenfield’s lens defiantly in a full-page close-up. The monstrous star of the TV series Toddlers & Tiaras is quizzed by her mother/enabler, Mickie: “What does beautiful mean to you?” “That I get money,” replies the tot, “and I’ll be a superstar. Money, money, money.” Greenfield’s image-obsessed informants show the poignancy and absurdity of trying to adapt to a society that has its incentives all off: the plastic-surgery addicts, the princess wannabes who look to Disney for existential solutions, the sensitive kid at a fancy school who “wants to look ‘rich’ like the other kids” and “saved up to buy designer items when his family could no longer afford them.” And pampered spenders, like the Toronto socialite with Birkins in “almost every color” who hosts a $250,000-per-table charity gala (“I want to make sure Oscar [de la Renta] comes to their table to say hello. . . . That’s very important because people are looking for a return on investment”). We gobble up this voyeuristic feast of societal symptoms. The eye of the camera—neutral as money itself—reveals capitalism’s catastrophe of indifference. It is left to us to bear witness. We gawk, covet, judge (you know you do!), chuckle, and despair while we enjoy the schadenfreude, Greenfield’s fab compositions, and her eye for incongruities usually normalized by the lens of wealth (like the “security guard outside a mansion whose owners are hosting a UNICEF Women of Compassion luncheon,” or the yoga class dwarfed by supermodels on a giant Tiffany ad that dominates the “town square” of a luxury mall). The abject fetishism of status symbols would be comic if it weren’t also so brutal, creating real pain and wrecking lives.

Like beauty and/or fame, the “Dream Home” became a measure of self-worth

for aspirational consumers. In “The Fall,” Greenfield depicts the damage when unregulated banks enabled a global mania for real-estate speculation that went bust in 2008, inducing collective greed withdrawal and, for many, ruinous debt. LA real-estate analyst Jack McCabe cites the prevailing view that “bigger and better makes you worth more, increases your value as a human being. . . . It was greed, pure and simple.” On the opposite page, we see a 2008 photo of a real-estate agent and his son romping in a lavish lagoon-like family pool. It’s dryly captioned, “Borrowing against the value of his house during the real-estate boom, Brian built his family a tropical backyard.” One doubts they are still enjoying it.

Greenfield documents postcrash ghost towns: foreclosed houses hastily abandoned by families who’d hoped to upgrade and half-built speculative developments littering landscapes from the US to Dubai. She juxtaposes two nearly identical shots, one taken in California and one in Ireland; in each the brown lawn of a neglected home is a sad foil to the green one next door, and a drag on its value. In Dubai, expats lured by “the illusion of a place of perpetual prosperity,” who were suddenly fired when financing for their employers’ luxury housing projects collapsed, fled their plush digs to avoid debtors’ prison—without jobs, they would lose their visas, and their assets would be frozen. Greenfield shoots a luxury car abandoned at the Dubai airport with loser etched in dust on the windshield. Making use of other people’s foreclosed dreams, in Ireland a group of artists and musicians live communally in a “recession mansion”; near San Jose, resourceful college kids rent a derelict McMansion.

Photographed in the stately Old Library at Trinity College, Irish economist David McWilliams explains how a crash exacerbates toxic inequality: “Crashes have a great tendency to be marketed as ‘We’re all getting poor together,’ but, in actual fact, in a crash the very rich become much richer. . . . If everyone is poor together, nobody minds. You only get pissed off when your neighbor starts getting rich. . . . The problem with inequality is that a huge number of people believe they don’t have a stake in the society.” A shrink who specializes inWall Street executives sees “many patients with ‘narcissistic tendencies’ who believe they deserve any amount of wealth they can accumulate.” He notes the culture of envy they abide in, the “greed high” of shopping, and then the despair. “It’s easy to scoff at people obsessing about their Birkin bags, but I think it says something about their mental health that should be addressed.” From behind the balding head of a patient with a Burberry jacket as repoussoir, we see the doctor’s listening face flanked by a wall of diplomas.

These mental-health issues inspire planetwide business models, as rich-people enablers hustle to coddle the loaded. The “Miss Manners of China” with a Harvard MBA shows unpolished moneybags how not to act like bumpkins. She teaches skills such as proper pronunciation of foreign luxury brands: “‘Air-mes,’ not ‘Her-mees.’” For those with too many homes to live in, an estate manager will use their stuff for them to keep things humming. He explains: “Wealth affords you the ability to be insulated, and that insulation can be extremely lonely. There is a certain resourcefulness that’s taken out of your DNA and replaced with being able to afford it or buy it as a service.” A prominent Russian Rolls-Royce and art dealer steps up to help “helpless” new money: “There is a lot of talk now about the need to help the poor . . . [but the rich] need to be helped as well. . . . They need to be taught the world of culture, the world of art, because all of them are helpless about it.” In one fabulous shot, Greenfield expertly captures a world of status symbols with human appendages: A costly fur coat with a Céline purse seems to look at a (presumably pricey) painting. The gallery owner boasts that at one of his openings, “You’ll see twenty-five crocodile Birkin bags.” That’s culture!

In the bell jar of Generation Wealth, there are some glimmers of sanity: Unlike the US (thanks, Obama!), Iceland refused to bail out its banks and now thrives as a sustainable economy, rediscovering fishing, knitting, and social justice. Rock musician–turned–Best Party politician Óttarr Proppé, currently Iceland’s minister of health, poses impishly in a mustard suit he wears to photobomb group photos of square colleagues. “When things are very unequal, I think it’s very hard for individuals to find dignity in themselves,” he says. “We were at a point where a different view of things was important.” In Berkeley, California, cheerful environmentalist Annie Leonard lives communally with neighbors to “avoid waste and the stress of consumerism” and opines from her hippie oasis, “If we peg our level of satisfaction to these commercialized values, we will never, ever have enough. . . . Once you get on that path, it’s like being a slave.”

It’s impossible to do justice to this Boschian tableau. The cumulative effect is haunting and clarifying, and Greenfield’s closing image is a rich summation: At Magic City, a strip club in Atlanta, a dancer clad only in sparkly heels scrambles to grab dollar bills flung by a “baller” who has made it rain. DJ Esco philosophizes: “Money is power. It’s saying, ‘I can do whatever I want. I can throw this money on her ass. I don’t give a fuck about this money.’”

If only the US, like Iceland, could learn from the crash and revert to a sustainable culture organized around human dignity! But neoliberalism and its shortsighted values continue to exacerbate inequality and hollow out our institutions into profit funnels for Wall Street. By the end of the book, it’s clear that the delusions and waste of Generation Wealth are left still largely unaddressed. What could possibly go wrong?

Rhonda Lieberman is a writer in New York.