The mid-twentieth-century Spanish Mexican artist Remedios Varo once wrote a fan letter to Gerald Gardner, known in the UK as the “father of modern witchcraft,” in which she let him know that in Mexico City he was not alone: “I, Mrs Carrington and some other people have devoted ourselves to seeking out facts and data still preserved in isolated areas where true witchcraft is still practiced.” They say witches often come in threes, and Varo and her best friends, the painter and writer Leonora Carrington and the photographer Kati Horna, formed their own coven in the city’s Colonia Roma neighborhood. After President Lázaro Cárdenas opened Mexico’s borders to European refugees in 1942, Carrington, Horna, and Varo were among those who found sanctuary. Roma attracted many expat artists, but the trio mainly kept to themselves—all three interested in the intersection between art, mysticism, and the occult. Not everyone was a fan—Frida Kahlo apparently called them “those European bitches.”

Theirs was a distinctly feminine Surrealism, unfettered by the iconic men of the European movement. In the world they created, sans male leads, they were Surrealism’s leading ladies. In Horna’s seminal 1962 black-and-white photo series “Oda a la necrofilia” (Ode to Necrophilia), her ingenue is a mysterious woman in mourning circling a deathbed and seducing a corpse that is represented by a blank mask. Several of the photos ran in the experimental journal S.nob, though few people realized the woman—who goes from fully cloaked to completely naked—was actually Carrington. Even among her equals, Carrington inevitably played muse once in a while, but Horna’s casting of her signified something more important: Here, the creators were the cast and they also happened to be women. Men simply didn’t merit note.

Carrington, who lived until 2011, has been called “the last Surrealist.” She was born in 1917 in Lancashire, England, to a wealthy family. At age nineteen, rebellious and unruly, she met Max Ernst at a party and ran away with him to France. He was forty-six and married at the time. After he was arrested as an enemy alien and taken to an internment camp in 1940, Carrington ended up in Spain, where she suffered a nervous breakdown. She was sent to a mental hospital and disintegrated more direly, due to bad experiences with medications. She eventually fled Europe for New York City and then for Mexico, where she lived for the rest of her life. There, she wrote novels, stories, and plays, in addition to producing all sorts of paintings and sculptures.

In 2015, I went to Mexico City for the first time, with the excuse of retracing Leonora Carrington’s steps. Carrington had died just four years before and I could not get her work out of my head. A lot of writers I’ve loved feel of her ilk—Angela Carter, Clarice Lispector, Lydia Davis, Rivka Galchen, Rebecca Curtis, Mary Caponegro, and many others could be seen as inheritors of her style and substance. My friend the writer Karen Russell joked that we—Carrington, her, and me, plus Aimee Bender, Kelly Link, Helen Oyeyemi, and Laura van den Berg—should be called Team Sorceress. So perhaps I went in search of our patron saint, in the country Salvador Dalí famously announced, after a brief visit, that he couldn’t return to: “I can’t stand to be in a country that is more surrealist than my paintings.”

Even in 2015, Mexico City seemed the perfect place for surrealism: Here was a palette of candy-colored adobe homes lit luminously against a brooding silver sky. On my second day there, I decided to look for Carrington’s house, which some Google detective work had turned up: number 194 on Calle Chihuahua, in the heart of Roma. As I walked over, I dreamed of the odd splendor that might await me at its exterior—but those fantasies immediately collapsed upon seeing number 194. It was a white condo you could find in any place where twenty-first-century gentrification has done its damage.

Carrington, who often hosted parties here, was known for snipping off locks of her guests’ hair when they were sleeping and then serving it to them the next morning in her famous “hair omelets.” Stories followed her all through Mexico City: She was apparently courted by Luis Buñuel, who invited her over to his place one evening—in essence propositioning her, which she took him up on. But the spell was ruined when she found his digs barren, like a motel. Carrington smeared his walls with her menstrual blood to give the place some life, and that was that.

She was no average woman, certainly not someone who’d just give up and live in a new condo. I quickly instagrammed the building and a few minutes later someone in the know reminded me that her home was said to be behind a wall. That made sense, and I accepted that on this trip this was all I could have.

It wasn’t until I made it to Mexico City’s version of Park Avenue, the Paseo de la Reforma, that I finally saw my first Carrington: Cocodrilo, the famous bronze sculpture of five crocodiles riding in what appears to be a crocodile-shaped boat helmed by a bigger crocodile. The most surreal aspect was how it was tucked into a bustling shopping hub, folks on their lunch hours sitting against its platform with iced coffees and sandwiches. Somehow only in the casual chaos of Mexico City could Carrington look so incredibly ordinary. I left the city understanding her setting more than her; it would still be some time until I realized that to love Leonora Carrington properly was to love her exterior worlds, her internal states being only a skewed reflection of all she knew to be real.

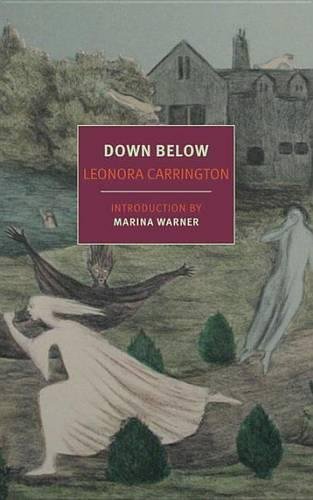

This spring, New York Review Books and Dorothy, a Publishing Project have released several volumes of Carrington’s work to coincide with the centennial of her birth. The Collected Stories is out from Dorothy, while NYRB has published Down Below and her children’s book, The Milk of Dreams. Although Carrington comes in and out of style every few years, it seems, if anyone needed a truly comprehensive introduction to her, this is the year.

I found what I considered the real Carrington when I landed on one of her most famous short stories, “The Debutante.” This 1937 story begins: “When I was a debutante, I often went to the zoo. I went so often that I knew the animals better than I knew the girls of my own age. Indeed it was in order to get away from people that I found myself at the zoo every day.” The story, all told in a sort of brassy deadpan—like a fairy tale that doesn’t know it’s a fairy tale at all—naturally concludes with the narrator’s hyena friend attending, in her place, a ball, which ends rather disastrously. It’s a testament to the surrealism of Carrington’s very person that this story is interpreted as autobiographical.

This is the first time I’ve seen many of her other stories, which have always been hard to get hold of. Trademark off-kilter, otherworldly, magical Carrington does not disappoint. The syntax and diction are always startlingly simple, completely accepting of whatever paranormal or dreamlike phenomenon they describe. A crisp, taut minimalism is always her mode. Animals populate every page and they are always strange. In one of her most wildly entertaining stories, “White Rabbits,” glamorous lepers with skin like stars inhabit a New York apartment at 40 Pest Street, with one hundred pet rabbits that feast on rotting meat. Another parable, “My Mother is a Cow,” begins—of course—“Our family is modest, my mother is a cow,” while “The House of Fear” begins, “One day toward half past midday, as I was walking in a certain neighborhood, I met a horse who stopped me,” and soon we are told that “there were a number of creatures in ecclesiastical dress.” Indeed, animals often merge with the sartorial in unexpected ways; in “Cast Down by Sadness,” Carrington has a character quip, “I have a dress made entirely of the heads of cats.” And animals as food are perhaps her favorite bestial incarnation, though the culinary is always something else in Carrington’s mind, and it’s never very appetizing. In “The Sisters,” Carrington offers this description: “Meat, wine, cakes, all half eaten, were heaped around them in extravagant abundance. Huge pots of jam spilled on the floor made a sticky lake around their feet. The carcass of a peacock decorated Jumart’s head. His beard was full of sauces, fish heads, crushed fruit. His gown was torn and stained with all sorts of food.”

Best of all, perhaps, is the world of the dead, which is everywhere and disturbingly animate. In “The Happy Corpse Story,” she writes,

Being full of holes and dents, the corpse could talk out of any part of its body. “Now,” said the corpse through the back of its head, “I shall tell you a story.” The youth heaved a groan like a death rattle. He felt too preoccupied to listen. Nevertheless the story began. Think of listening to a story told straight into your face out of a hole in the back of the head with bad breath: surely this must have troubled the delicate sensibility of the young man. However, what can’t be cured must be endured.

For Carrington, the aphoristic and proverbial serve an ordinary plot function—it’s as if every story is an opportunity to spin a proverb into an edict. It is only natural that this sensibility would create the best children’s stories imaginable—the kind for the sort of children for whom Edward Gorey spun stories: the bad children, the ones with the most wicked imaginations. In The Milk of Dreams—its illustrations apparently drawings from the walls of her home in Mexico—we have a typical Carringtonian menagerie that borders on a certain perverse edibility: crocodiles, a monkey, a rabbit, a bird, an elephant, a horse, flies, a vulture (who ends up set in gelatin for a dessert), and many monsters—including a sofa you can feed that gets stuffed with vitamins. I’ve often heard that Carrington’s wild imagination sprang from the folktales her old Irish nanny told her mixed with the Mexican folklore she picked up during her long exile, but perhaps her struggles with madness played a part in her dedication to creation. What better way to keep the demons placated than to give them a home in one’s art?

This is where Down Below comes in. First published in 1944—and revised for accuracy by Carrington in 1987—the memoir chronicles the period after 1940, when Carrington descended into complete madness. Surrealism’s literary forefather, André Breton, had convinced her to write it. Every person who was fascinated, as I was, by tales of Carrington’s post-Ernst breakdown—every artist who has known insanity, as I have—will be happy to know that Carrington kept such meticulous records. More often than not, her account feels too close for comfort. Carrington tells the story with startling honesty, sugarcoating absolutely nothing.

The book begins with Carrington facing the label “incurably insane” from the very first sentence. We find her poisoning herself with orange-blossom water to induce vomiting after Ernst is arrested and she is alone, in a state of inconsolable grief. It’s immediately clear that Carrington is not going to apologize or write from a distance, from where she now knows better. The project here will be to transport us to the heart of delusion. She does not tone down her ideas one bit: “I ceased menstruating at that time, a function which was to reappear but three months later, in Santander. I was transforming my blood into comprehensive energy—masculine and feminine, microcosmic and macrocosmic—and into a wine that was drunk by the moon and the sun.” As always, the Carringtonian audacity feels (at least) twofold; menstruation is nothing to leave out, and connecting it to the mystical is nothing to shy away from. Madness seems to be linked to the purity of the animal state, whereas “cures” and civilization are seen as threatening. The most daunting rock bottoms for Carrington come when she is given the drug Cardiazol, an experience, we somehow come to feel, far worse than the loss of a first love or exile from a home continent infested with Nazis.

The scholar Marina Warner’s intro takes up nearly one-third of the book and is an essential part of it—the two were apparently quite close. Warner is at her best when she looks at Carrington through the story of twentieth-century feminism. This could have been a cautionary tale, but it turned into a saga of unlikely triumph, the kind one would have wished for Sylvia Plath, for example: “Leonora in her crazed state met surrealist ideals of escape from bourgeois convention. Her torments confirmed her status as a kind of hierodule, a holy and erotic nymph who uniquely knew by instinct certain delinquent mysteries that the older men of surrealism felt they could not reach without her help.” They may have drawn her in for the wrong reasons, but she left with her own right ones.

Carrington’s heroine Marian Leatherby, in her darkly comic novel The Hearing Trumpet, offers a sort of celebration of elderly feminism, though the study came to Carrington a whole six decades early—Marian is ninety-two, but Carrington composed the book when she was in her thirties. She herself lived to ninety-four, and you get the feeling she didn’t miss her youth, which had for so long kept her as the object of creation instead of the creator: “Beauty is a responsibility like anything else; beautiful women have special lives like prime ministers, but that is not what I really want,” Carrington once said. She was lucky that her muse days were pretty much done by the time she was into her late twenties—or rather, she made sure they were, by making her own way. The twentieth century struggled, as this century does, with women whose lives and looks are deemed as fascinating as their art, but Carrington was adamant about directing your attention from her person right back to the page and canvas every time. It’s a testament not just to her talent but also to her character that we know her today as something more than Max Ernst’s girlfriend. But she’s still not as well known as she should be, and for that we can blame our time as much as any other. What better adage for our era, one still wrestling with a place for feminism, than Carrington’s: “Most of us, I hope, are now aware that a woman should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be Taken Back Again, including the mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen or destroyed.” She was also known to say, more simply, “I warn you, I refuse to be an object.”

Porochista Khakpour’s third book, the memoir Sick, will be published in June 2018 by Harper Perennial.