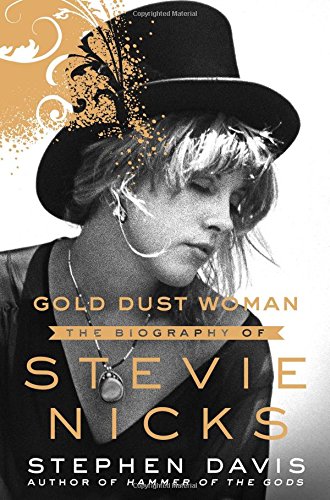

Early in Stephen Davis’s workmanlike unauthorized biography of Stevie Nicks, we witness the circumstances of her most enduring creation’s birth. Twenty-six-year-old Nicks—sick and tired of waitressing; struggling with the controlling behavior of her boyfriend, Lindsey Buckingham; fighting to keep their flailing band, Buckingham Nicks, alive—was holed up in sound engineer Keith Olsen’s house. High on LSD—“the only time I ever did it,” Nicks says—she spent three straight days listening to Joni Mitchell’s just-released album Court and Spark on Olsen’s giant speakers. The record inspired her on both a technical and a thematic level. What Mitchell was describing, with unusual candor, were the perks and pitfalls of being a female rock star. When she heard it, Nicks had a premonition, or received a warning. After she came down, she composed the song that would make the prophecy of megafame real and that she would perform in various versions for decades to come. She left the demo cassette of “Rhiannon” for Buckingham with a note: “Here is a new song. You can produce it, but don’t change it.”

This story, like many of the tales people tell about Nicks and that Nicks tells about herself, is goofy and vague but still suffused with genuine magic. The Stevie Nicks legend is full of prophecies: She has always had dreams that literally come true. Songs like “Landslide,” “Gold Dust Woman,” and “Silver Springs” predicted her future and bound her forever to a onetime lover whose fate was to “never get away from the sound of a woman who loves him.” What is the secret of her near-mystical communion with the audience? How did she survive being in a band with not one but two acrimonious ex-lovers? Why did she ever put up with Buckingham, who is portrayed from the very beginning as angry, sarcastic, boorish, cruel, and even violent? Gold Dust Woman has a lot of detail about buffets, drug quantities, costumes, and tour schedules, but I never really expected it to answer those kinds of questions. Answers would have required Nicks to speak to a biographer, to remember accurately, and to be honest. None of that seems likely to ever happen; Nicks has been giving essentially the same interview for decades and has no incentive to set the record straight. Her music speaks for itself and her fortune and legacy are secure.

Maybe a better question, then: Even though I doubted it would offer any real insight into Stevie’s soul, why was I eager to read this and every other book ever written about her? Plenty of women in the history of popular music have written ubiquitous hits and created memorable aesthetics and rituals around their performances. But no one else has inspired an event like Night of a Thousand Stevies, an annual drag ball with dozens of tribute performances and hundreds of attendees. It’s been going on for twenty-seven years. Nicks’s songs are a crucial part of her appeal, but her persona—her shtick—is inescapably compelling. When people think of Fleetwood Mac, they think of Nicks, flaunting the incredible wingspan of her shawl in a spotlight as the rest of the band recedes into shadow.

It’s safe to say that this wasn’t what Mick Fleetwood initially envisioned when he brought her into the band. The Mac had already been around for eight years in its Cream-esque British-blues incarnation when Fleetwood chanced on a Buckingham demo tape. Fleetwood wanted only Buckingham initially, but he and Nicks were a package deal. As a duo, she and Buckingham had almost a decade of gigs and one failed album under their belts; they were ready to try anything. She joined the band as decoration, twirling with a tambourine. Early reviews singled her out as the band’s weakest link, calling her singing “callow” and “raucous” compared to Christine McVie’s smooth alto.

It didn’t take long for the tables to turn. For years now, she has been the most powerful member of Fleetwood Mac. Various reunion tours, which the rest of them needed much more than she did, could have gone forward without Buckingham, could and did go forward without Christine McVie, and would certainly not have missed John McVie; Nicks is the one absolutely nonnegotiable band member. They were forced to incorporate her solo numbers into their shows, even though Buckingham generally refuses to play the heroic, protracted one-note guitar intro to “Edge of Seventeen,” which Nicks traditionally uses as a shawl change and, prerehab, used as a coke break.

Claiming this kind of power comes at a cost. Nicks decided early on that she would not have children; she cultivated a coterie of singing girlfriends instead of a family. She spends time in hotel rooms and hotel-like homes. She takes care of herself and her voice, but no one and nothing else. In one of her eventful life’s most bizarre twists, still mostly unexplained, she once married her best friend’s widower immediately after her friend died of cancer, but the three-month marriage was later annulled. That period is explained in the book as a desperate attempt to fill the void left by losing her friend, as Nicks told a reporter for Us magazine in 1990: “We were grieving and it was the only way we could feel like we were doing anything.” She has had many intense love affairs, but aside from the one with Buckingham, no long-term relationships that could be called partnerships. Even Joni Mitchell, so famously defined by her litany of love affairs and her early anthem about being “busy being free,” was married twice, once for twelve years. Nicks’s ballads about breaking up and breaking free resonate through the decades because they reflect a hard-won truth: No love is eternal, and no man is worth the loss of your freedom.

Like most people my age, I first became aware of Fleetwood Mac circa 1997, when the band was doing publicity for the reunion album The Dance by appearing on shows like VH1’s Behind the Music. The narrative superimposed on the band by that show, and by most rock-star biographies, is always the same: Success is followed by too much success and a riveting flameout, which is followed by treatment and recovery, which is followed by a triumphant reunion. Through this lens, Nicks’s story is simple and romantic: She and Buckingham, young and in love, made beautiful music together until the pressures of fame and success, plus drugs and suspicious minds, tore them apart circa Rumours. They can still summon vestiges of their love onstage, the story goes.

Gold Dust Woman almost incidentally eliminates the glamour and romance of the accepted narrative. It becomes evident early on that Buckingham was bizarrely possessive of Nicks and verbally abusive, and that their relationship was already 99 percent over before they joined Fleetwood Mac. Davis alludes throughout the book to the fact that Buckingham could be physically abusive but tends to stop just short of direct accusation: “This led to the inevitable shouting match (and maybe worse),” he writes of one early fight. The only incident he does describe in detail occurred twelve years after Nicks and Buckingham joined the Mac, when Nicks had already embarked on a successful solo career and the band was quite a few years past its prime. Most of the band wanted to tour to support Tango in the Night, but Buckingham was balking. After a heated argument in the rest of the band’s presence, he grabbed Nicks, slapped her, and started to choke her. “They all knew it wasn’t the first time he’d hurt her,” Davis writes. In the next paragraph, he’s back to describing tour logistics and personnel.

I got into solo Nicks following a breakup. “Take on the situation, but not the torment,” she advised me every morning in my headphones as I walked to the subway listening to “Think About It.” “You know it’s not as bad as it seems.” This was good advice, if a little oversimplified. The situation, it seems to me now, was a lot worse than I knew. It was worse than I allowed myself to believe at the time, and even for years later. It was worse than I allowed myself to write about. Before reading Gold Dust Woman, I had thought of Lindsey Buckingham the same way I’d once thought of my ex—as a bad boyfriend, a talented, troubled guy, a beautiful but self-destructive problematic fave. Time makes you bolder; I now think of them both as abusers. I consider myself lucky to have escaped and maybe Nicks does, too. Lacking much information beyond her lyrics, it’s easy to project whatever I want onto her. She entered my life when I needed her, and for that reason I think of her almost as a friend and confidant; someone older and wiser who experienced what I did and was ennobled rather than destroyed by it. It doesn’t even matter whether or not any of that is true.

But it’s more complicated than that. There’s a reason Nicks and Buckingham are trapped endlessly rehashing their decades-old conflicts onstage, beyond just the fact that it’s profitable. The idea of love as a power struggle, for most heterosexual-leaning women, is endlessly relatable. When writing “Rhiannon,” Nicks grafted the flotsam drifting around her brain after reading an airport novel about Welsh witches to an earlier Buckingham Nicks track, probably a Buckingham composition, called “Will You Ever Win?” The theme of games with winners and losers often snakes through Buckingham’s lyrics. Nicks’s lyrics, of course, tend toward the elemental: She escapes by becoming part of the wind, being taken by the sky, flying away like a bird, being a storm. But her tormented and tormenting ex-lover is a “silver spring”—a well of inspiration. When I first heard this song, I thought that was a compliment, and maybe it is, in a way, but not in the way I had thought.

Emily Gould is the author of Friendship (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014).