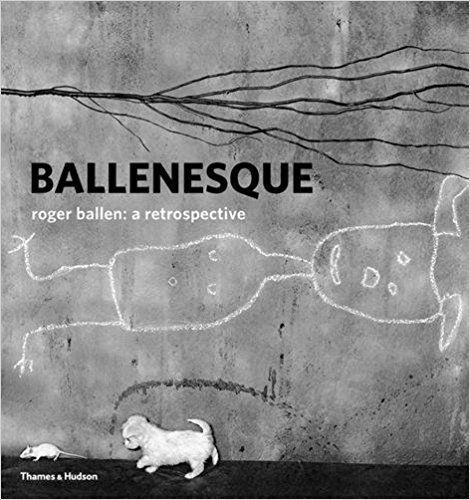

AMONG THE EARLIEST IMAGES displayed in this sizable account of Roger Ballen’s nearly fifty-year career is Dead Cat, New York, 1970. In the foreground of the photo, a feline—mouth agape, teeth bared, its body stretched as if scampering toward the viewer—lies on the side of a country road. The blur of a car racing away in the upper-left corner of the frame provides a witty counterpoint to the animal’s eternally stalled dash. Thus, at the outset of his career, Ballen was already compelled by the motifs that would energize his work for several decades to come: animals, lurid corporeality, and theatrical display. A longtime resident of Johannesburg, Ballen grew up in New York City, where he met Hungarian photographer André Kertész. In this volume’s lengthy autobiographical text, Ballen credits the older artist with his own “understanding of enigma, the quixotic, and formal complexity,” qualities present even in his documentary work of the ’70s and ’80s. Froggy Boy, USA, 1977, exhibits a Diane Arbus–like eye for the unsettling moment; this variation on Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962 replaces the explosive with a tightly clutched frog. In time, Ballen turned to elaborately staged compositions that can be provocative—a hand rises from a box to grasp a goose’s neck—yet sometimes overly so. A domestic scene in which a dog stares into the camera while resting against a sleeping teenage boy’s back is bent sinister by the crucified doll on the wall above them. And if the placid scene isn’t sufficiently undone by that dire addition, there’s a sign reading god just below the doll’s feet.

Ballen further enhanced these tableaux vivants with his own graffiti-style drawing and painting on walls, bodies, and objects. These black-and-white photos are alive with the chaotic eruption of scribbled figures and errant lines even as the subjects, both human and animal, are precisely positioned. The tension between static bodies and restive embellishment is further amplified by a sense of confinement: We’re always inside, far from natural light, and seemingly far from breathable air. Culled from the monograph Asylum of the Birds (2014), the photo titled Take Off (above) sets contesting elements—immobilized birds and drawings of birdlike planes in exuberant flight—around a garishly masked person who holds one of the winged creatures in its mouth. The strong odor of the madhouse attends this androgynous figure with his or her shapeless garb, tousled hair, impossibly wide eyes, and devouring maw, but the drawings and the toy plane in hand suggest the fanciful domain of childhood. Although the face is hidden, the figure’s inner turmoil is rendered explicit. Like so many of Ballen’s images, this parable of flight and frustration seeks out the emotional densities of its subject to bring viewers news from that bleak core.