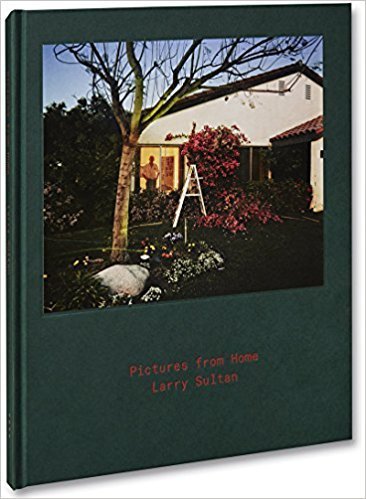

PICTURES FROM HOME wonders why you never call. Larry Sultan’s influential photobook of his parents, Irving and Jean, in their suburban Camelot must make every reader itchy to phone their family. Large-format color portraits of the elder Sultans posing or padding around the house are interspersed with home-movie stills and plainspoken text, including musings from Sultan about his motivations and interviews with his subjects.

The book, first published in 1992 and recently reissued with new material, has aged perfectly, providing a sugar high of pure upper-middle-class white Southern California kitsch—heavy on the foil wallpaper, wall-to-wall carpet, and golfing paraphernalia. While Tina Barney was busy capturing her wealthy New England clan and Philip-Lorca DiCorcia was paying to photograph LA hustlers, Sultan got Mom and Dad on the line.

Returning home for periodic visits over the course of a decade, he gave himself an unusually unsentimental assignment. In the book’s text, he writes that he was galled by the era’s prevailing Reaganite “family values,” that cult of cheerful striving: “I wanted to puncture this mythology . . . and show what happens when we are driven by images of success.” Like any good observer of suburban subtext, Sultan finds thin optimism and soft-pedaled disappointment apparent everywhere.

His parents were simultaneously game and wary to participate in the project, one pitched somewhere between fact and fiction, documentary and performance. They aren’t posed, exactly, but they aren’t unposed either. It all feels true to life, offering an uneasy view of the Sultan family’s whole rigmarole: guarded openness and familiarity-bred contempt; hope and tolerance and low-grade tenderness. Irving is a Caddy-driving go-getter who likes nothing better than to whack a golf ball clear to the Pacific. When it comes to relating to his son, the younger Sultan reports, “he has a knack for finding the sore spot.” Jean is harder to read, enigmatic, perhaps because Sultan features her less directly. But she’s not bashful; she’s fond of bright blouses and boasts to her son that she once sold $18 million worth of real estate in a year, adding, “I think I’m the greatest saleswoman around.”

Sultan’s vision is more than wan suburban malaise or retro-fab remembrance. Pictures from Home’s mélange of forms and approaches resolves into a larger truth: In parents, a grown child sees the past, present, and future all in one go. It’s hard not to take their aging as omens of our own and harder still to see them clearly through the scrim of our wants, gripes, fond feelings, and fears. Sultan peels back these layers and holds them up to the light—it’s delicate work, and hard won. Son knows best.