I LIVE IN MARFA, TEXAS, a town sixty miles from the US-Mexico border, a place small enough that every high school senior gets a mini-profile in the weekly paper. Last year, the two dozen graduates answered questions about the clubs they’d belonged to and what their post-school plans were. The girls all said they wanted to study cosmetology, preschool education, animal science, or business. Half the boys wanted to be diesel mechanics or welders; the other half planned to join the Border Patrol.

Perhaps these teenagers were drawn in by the digital signs that flash along roadsides all over the rural Southwest: NOW HIRING, a message that’s more potent since the oil-and-gas industry stopped being a sure bet. Or maybe they were enticed by the annual Border Patrol open house, in which high school students play a virtual-reality game where they have to decide whether or not to shoot a man who staggers out of a car and lunges toward them. The starting salary for entry-level agents is upward of $50,000, once overtime is factored in; you don’t have to be a college graduate.

I thought about the boys in Marfa’s high school class of 2017 a few months ago, when the US Border Patrol was in the news for the latest travesty in a year in which the travesties happened in such quick succession that they almost started to blur together. This time, it was the story of Rosa Maria Hernandez, a ten-year-old with cerebral palsy who had lived in the US since she was three months old. Rosa Maria and her cousin were stopped by Border Patrol while she was on her way to get gallbladder surgery in Corpus Christi, Texas. Agents, having determined she was in the country illegally, followed her to the hospital and waited outside her room; when she woke up, they whisked her away from her family to a juvenile detention center. (Rosa Maria has since been released to her parents, but it is unclear whether she will be deported.) “These guys are evil,” people tweeted, and “this is insane.” An East Coast friend gave me a sticker that, at first glance, looked like it featured the Border Patrol logo—but what it actually said was U.S. MURDER PATROL.

This year, more than ever, I’ve been acutely aware of how much rhetoric swirls around the border—and how much of it comes from elsewhere, DC or New York or the vague no-place of the internet. Read enough op-eds and takes and tweets about the border, and you can start to forget that it’s a real place. But then, of course, the border had become surreal—more feared than known, dense with symbolic portent—long before the current administration took power. In 2008, a tech start-up called RedServant created a platform that gave “virtual deputies”—that is, civilian volunteers—access to real-time footage from surveillance cameras along the Texas-Mexico border. Participants were supposed to scan the feeds, looking for something suspicious. The interface looked and sounded like a video game, with different “virtual stakeout” objectives: “If you see people walking along this trail carrying backpacks or packages please report this activity”; “please report . . . vehicles that are parked along road”; “look for individuals . . . in a boat crossing water.” The border region had found its fullest expression as the terrain for a video game, as someplace unreal and contested, where points are scored and violence erupts but no one actually exists. RedServant’s use of gaming tropes served as a distraction from the fact that at the actual border there were real bodies, moving through a real landscape, and that the dangers they faced were also very real.

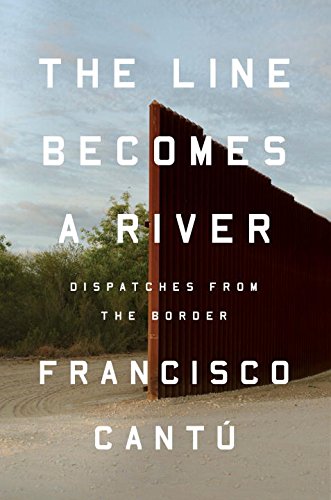

The same year that RedServant launched its crowdsourced border-enforcement platform, a young man named Francisco Cantú enrolled in the Border Patrol’s training academy. Among his fellow trainees, Cantú stuck out; he was a college graduate, with a degree in international relations. Unlike many of the men and women he trained alongside, Cantú wasn’t thinking of the Border Patrol as a lifelong career; he had vague plans to go on to attend law school, and then perhaps practice immigration law, or work to shape border policy. But Cantú’s stint in the US’s largest federal law-enforcement agency ended up changing him in ways he didn’t expect. Those four years and their aftermath form the foundation of his lyrical, morally complex book, The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border.

What, exactly, are you doing in this job? Cantú’s mother asks him during his time in the Border Patrol. At first, Cantú insists that he’s looking for a practical education in the issues he’s been reading about in textbooks, the kind of perspective you can only get from being on the ground, right up against the thing itself. “Whatever it is,” Cantú tells his mother early on in his career as an agent, “I’ll never understand it unless I’m close to it.”

Accordingly, the first third of the book hews close to Cantú’s personal experience, and to the border, as he makes it through the academy and takes a job working as a field agent in Arizona. Field agents are the grunts of the Border Patrol; Cantú and his fellow agents stake out hillsides, search for drug caches, patrol dirt roads, track migrants moving through the desert, and process people for deportation. As in a war memoir, there are stretches of boredom, bureaucracy, and waiting, interrupted by action. Cantú foregrounds the emotional tone of the work: the helplessness and fear and camaraderie; the moral queasiness that bubbles up when facing frightened children; the way pursuit can sometimes feel like a game that you desperately want to win. There are mountain lions, car chases, and bundles of drugs discovered in the desert. But mostly there are quieter moments, like Cantú’s brief encounter with a man from Michoacán who, as he’s being processed for deportation, asks if there’s any work he can do while he waits for the bus that will take him back to Mexico: “I can take out the trash or clean out the cells,” he tells Cantú. “I want to show you that I’m here to work, that I’m not a bad person.”

One of Cantú’s rationales for joining the Border Patrol is that, because he speaks Spanish and has lived in Mexico, he will be a better, more empathetic servant of the state. “Good people will always be crossing the border,” he tells his mother. “At least if I’m the one apprehending them, I can offer them some small comfort by speaking with them in their own language, by talking to them with knowledge of their home.” There are moments of shared humanity between Cantú and the people he’s helping to deport, like when he gives his own undershirt to a man who is about to be sent shirtless back across the border, or when he and his partner applaud the woman who belts out “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” in the back of their patrol vehicle.

But the limitations of those “small comforts,” particularly when offered within the bounds of an inhumane system, quickly become evident. One day, Cantú is instructed to pick up two “quitters”—that is, migrants who have given up on their arduous trek. He’s directed to a small adobe church, where he finds a couple lying on a blanket in front of the altar. The husband tells Cantú that they’d crossed the border four days ago, but that their group had left them behind when they couldn’t keep up. His wife, who is six months pregnant, explains in English that she grew up in Iowa, and had gone back to Mexico to care for her siblings after her mother’s death; she had been hoping to return to the US so her baby could have better opportunities. Cantú feels for them in their plight, and yet his empathy is disorienting in its futility:

In the driver’s seat I turned to look at the couple through the plexiglass. The man held his wife and gently whispered to her, cradling her head. Just before I started the engine I could hear the soft sound of her sobbing. As I drove through the unmarked streets of the village, trying to find my way to the highway, I felt for a moment that I had become lost. Beyond the last house, I saw a white dog in the darkness at the edge of my headlights, staring into the night.

Back at the station, Cantú sorts through the couple’s belongings, confiscating their belts and shoelaces, filling out their deportation paperwork, and then moving on to other cases. By the end of the evening’s shift, he realizes that he has forgotten their names.

Cantú intersperses these vignettes of his work as a field agent with brief stories about the history of the border itself, particularly the successive attempts, beginning in the nineteenth century, to delineate the territory, first with piles of stone, next with iron obelisks, and, ultimately, with fences and walls. Establishing a border line was a regrettable check on the young nation’s “inevitable expansive force,” as William H. Emory, commissioner of one of the early expeditions, put it, but the compulsion to define and divide proved stronger, even, than the desire to expand and conquer.

For the first hundred pages, the narrative of The Line Becomes a River sticks close to Cantú’s perspective—so close that it’s hard to see, exactly, the context he’s operating inside of. Other than intermittent forays into the stories of early border expeditions, there is not much history here, and even less policy analysis. We have ten thousand more Border Patrol agents now than we did before George W. Bush was president, but you wouldn’t necessarily know that from reading The Line Becomes a River. The names of presidents, current or past, barely warrant a mention. Unlike other border books, Cantú mostly avoids digging into the political and economic factors that have fed border militarization and narco violence: nafta, 9/11, the waning power of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Mexico. The period when Cantú worked as an agent coincided with the peak years of Operation Streamline, the federal government’s mass-deportation program, which has prosecuted more than 750,000 people since it began in 2005. But Streamline only enters the story obliquely—at least at first.

These elisions are by design, not neglect; Cantú clearly knows his border history. Early on in his training, he ventures to explain why migrants cross the desert in the brutal summer months to his fellow trainees over drinks: “Migrants used to cross in the city . . . in places like San Diego and El Paso, until the Border Patrol shut it all down in the nineties with fences and new recruits like us. Politicians thought if they sealed the cities, people wouldn’t risk crossing in the mountains and the desert. But they were wrong, and now we’re the ones who get to deal with it.” This policy, benignly known as “prevention through deterrence,” was instituted in 1994, and has contributed to the deaths of thousands of people; the ACLU has deemed the results to be a humanitarian crisis. Cantú’s colleagues aren’t interested in his academic take on the job they’re vying for; they lose interest, look away. “Sorry for the lecture,” he apologizes. “I studied this shit in school.” The lesson is implicit: To operate in this world, you can’t think too hard about what you’re doing, or why. But Cantú is too sensitive and perceptive a narrator to block this knowledge out entirely. Dread creeps in at the edges of his experience; he grinds his teeth in his sleep and has nightmares of wolves.

As Cantú gets promoted, first to a desk job at sector headquarters in Tucson and then to a position on an intelligence team based in El Paso, the narrative’s perspective widens, as if the daily urgency of the work has lifted enough that he finally has space to think. His stories of Border Patrol life sit next to accounts of the overburdened morgues in Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez, of his own family’s history in Mexico, of a regretful sicario, or cartel hitman. He quotes investigative reporters, academics, and poets. The logic linking these sections is more associative than argumentative; the effect is that of an impressionistic collage of border moments, border thoughts.

By the final third of the book, Cantú has left the Border Patrol. He is working as a barista in Arizona when his friend José gets ensnared in the cruel double bind of the border: Having traveled to Oaxaca to visit his dying mother, José, who was brought to the US as a child, attempts to return to his family in Arizona. He is apprehended, charged with illegal entry, and deported. José, whom Cantú portrays as almost a caricature of a model immigrant—a modest family man, a churchgoer, a hard worker—is transformed, via the refracted logic of the border, into a criminal. Cantú knows how this story plays out: Every time José is caught attempting to cross into the country illegally, he risks increased jail time.

In the courthouse with José’s family, Cantú finally directly confronts the outcome of his Border Patrol work:

I had apprehended and processed countless men and women for deportation, many of whom I sent without thinking to pass through this very room—but there was something dreadfully altered in their presence here between towering and cavernous walls, lorded over by foreign men in colored suits and black robes, men with little notion of the dark desert nights or the hard glare of the sun, with little sense for the sweeping expanses of stone and shale, the foot-packed earthen trails, the bodies laid bare before the elements, the way bones trembled from heat, from cold, from want of water.

With enough distance from the job, he finally begins to understand what the job was.

Midway through The Line Becomes a River, Cantú cites the work of cultural sociologist Jane Zavisca, who studies the figurative language used in media accounts of migrant deaths. There are the economic metaphors (“Death is a price that is paid, a toll collected by the desert,” Cantú writes, paraphrasing Zavisca); the migrant-as-animal trope (“‘Lured’ to the border by the prospect of well-paying jobs, migrants engage Border Patrol ‘trackers’ in a ‘cat-and-mouse game’ with deadly consequences”); the language presenting migration as a flood or deluge, as a dangerous and threatening surge.

I came to think of The Line Becomes a River as an attempt to counter these dehumanizing metaphors. Cantú has written an insistently humane book, or maybe just a human one. It does not presume to be an account of what the border means, or a theory about what should be done about it; rather, it’s an exploration of how the border feels, and what happens to the people who get caught in its gears. He got that close look he hoped for, and he has found a way to tell us about it. The account is necessarily fractured, incomplete—after all, a border is not something you can see in its totality. Cantú’s mother, a voice of moral clarity throughout the book, tells him, “You can’t exist within a system for that long without being implicated, without absorbing its poison.” Cantú has admirably taken on her challenge: “All you can do is try to find a place to hold it, a way to not lose some purpose for it all.”

Rachel Monroe’s first book, A Life in Crimes: Women, Murder and Obsession, will be published by Scribner in 2019.