Landing in the cratered, tawdry New York City of the 1970s, Duncan Hannah was a distracted art student who became a fitfully aspiring painter-illustrator. Before maturing into the stylish throwback artist he is today—the Evelyn Waugh of painting, beautifully reimagining Bridesheads past and bygone movie stars—he cut a resplendently androgynous figure on the CBGB scene, as both a born bon vivant and a straight sex object who wouldn’t give his gay patrons a tumble. (“A cocktease,” grumped his disgruntled harassers, who were legion.) At one point, he thought of calling this book Cautionary Tales. He was a Gatsby-in-training who was also, in the right light, a ringer for teen idol David Cassidy, an Under the Volcano–class alkie and devoted music facilitator, later identified in the 1996 NYC punk bible Please Kill Me as the “former president of the Television Fan Club.”

Television the band, not the medium. Their bedazzled music was the backdrop to a twitchy city of funky-but-chic parties and indulgent openings, a more-or-less-human arcade where Hannah found the likes of Warhol and Bowie and Hockney to be like well-padded bumper cars to bounce off amid the mad scramble. And if you happened to miss Nicholas Ray (the exiled-from-Hollywood director), you might still awaken from a bender to find Man Ray (William Wegman’s dog, not the artist he was named after) licking your face. The photographer and CBGB doorperson Roberta Bayley remembered the dapper, unflappable Hannah and said—or sighed: “He was just destined for beauty.” (Fun factoid: One time Francis Bacon wound up at Dunc’s door, but he was out getting drunk with Richard Lloyd, one of Television’s great guitarists.)

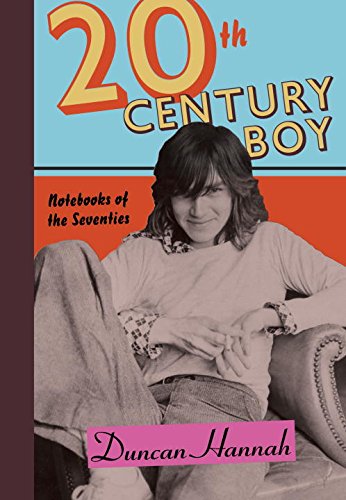

Hannah’s Twentieth-Century Boy: Notebooks of the Seventies (Knopf, $29) documents that impetuous, drugged-up scene with flushed revelry and latent apprehension. At the time, it was the dream of many a misfit youth to find, or make, a life that felt like an immortal record—a Velvet Underground of one’s own. And there Hannah was, with his Tiger Beat hair and beatnik gestures, a gorgeous kid doing the actual fieldwork, putting in long hours of debauchery and blackout. A sortie to see Roxy Music wends its way to a boho’s-who party at Larry Rivers’s loft, and thence by limo (with Warhol, Bowie, and Bryan Ferry) to a club where a “diesel-dyke” bouncer throws his shit-faced ass into the street: “The famous gutter that I’ve heard so much about. I made it!” A beat: “Now here’s where it gets weird.” He wakes up the next morning on the fifth floor of a condemned building at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue, with no idea how he got there or what happened to his money.

His journals are simultaneously breathless and detached, stills from a Nouvelle Vague film where he gets to be both Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg while cutting the whole show together à la Godard, Truffaut, Bertolucci, or Rohmer, depending on his most recent cinematic encounter. Ultimately, his moods, satyriasis, and aesthetic ambitions were of a sticky piece: an ongoing investigation into the limits of avant-gardism as a neo-nostalgic lifestyle. He tested the transgressive utopian waters by jumping into the deep end and playing Marco Polo with the track-marked sharks. These could be the adolescent notes for an Edward St. Aubyn novel about the rise and crash of the New York punk scene (its incest being confined to members of the in-crowd).

There’s always the question of how much has been tidied up, or of what has been omitted, when journals like these are brought to market. Hannah cops to trimming a fair amount of Kerouac-y youthful excess from his entries, and sometimes Twentieth-Century Boy comes off less as unvarnished dispatches than as a strategic reapportionment of facts and myths. Hannah claims, among other distinctions, that he first introduced two great duosyllabic luminaries to each other: “Eno, this is Nico. Nico, this is Eno.”

Maybe he’s exaggerating his role—I thought John Cale had already done the honors—but if Hannah’s a somewhat unreliable narrator, so too was most everyone else on the scene. Kids who gave themselves names like Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell were not big on verisimilitude. Look at Patti Smith—mythmaking was always the name of her game, and from the bargain-basement days of her song “Piss Factory” to the idyllic hindsight of the memoir Just Kids, she’s always had a genius for sensibility-as-cosplay. “Patti Smith told me she put me in a poem,” Hannah marvels, right before defending Smith’s pretensions against louche cannon Bette Midler, who had been spouting off next to him at the bar: Better a dilettante Dylanette than a rogue Andrews Sister!

Hannah filled twenty journals between the winter of 1970 and May of 1981. Beginning in Minneapolis as a sexually precocious teen, he’s a dissolute athlete training for the aesthete Olympics. He spends the summer of ’71 in Italy with his sister, soaking up the atmosphere, reading Nabokov, and listening to the Pink Fairies; the next summer he’s in London just as the Ziggy Stardust express goes on the road. This, it turns out, was a great awakening: “Bowie bare-legged and prancing about, mugging with Ronson in some king of gay droogy thing. Up at the front Mick Jagger was dancing in the aisles.” At twenty, our twentieth-century boy is already moving through a world that resembles the fast-forward sex scenes in A Clockwork Orange, brushing up against the ultraviolent edges without getting ensnared. He makes a list poem whilst drinking himself stupid to the Last Tango in Paris sound track: “I wonder if I have emphysema / I wonder if my crabs are gone / I wonder if Jenny really loves me. (Her Bard boyfriend is shooting heroin because he ‘misses her.’) / I wonder if I can paint well, write well. / I wonder how much I can see. . . . / I wonder if I should make myself another drink.”

Bottoms up: Within a few months, he’s swanning around the New York Dolls’ Halloween bash at the Waldorf Astoria in black-velvet overalls, connecting with perennial talent spotter Danny Fields. “I realize that I will be relegated to the position of dumb blonde,” he calculates, “but hey, let’s see where this leads.” For instance: Going to the nightclub Reno Sweeney with Leee Childers to see Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn’s debut. Having rocker and future transgender pioneer Wayne (now Jayne) County fondle his arm in a limo and say, “Ohhhh, you’d make such a beautiful junkie.”Getting baited by Lou Reed in high Lou style: “You could shit in my mouth. Would you like that?” They didn’t call New York “Fun City” for nothing, but Hannah passes: “Nooooo! What is with you people?!?”

As a giant free-for-all ball pit of the senses, “something like a circus or a sewer” (to quote Reed’s sagacious “Coney Island Baby”), the city was the best and worst of both netherworlds, with “Walk on the Wild Side” as your trusty Baedeker Guide, “Vicious” as the weather forecast, and “Berlin” as the cologne—the scent of Weimar Republic toilets, hot-dog carts, and sweet desperation. Every man-woman for his-herself, and the straight world against all. Here in Punktown, the boys prostituted themselves more than the girls, callowness was the rule, and substance abuse was a bigger problem than any other, though it was simply second nature—what coffee and doughnuts were to beat cops.

Once Hannah is an established, if not yet accomplished, figure—his art, like his alcoholism, was seemingly derivative and too retro—his journals settle into a steady, lulling whirl of bands and shows, women and blackouts, epiphanies and teeth-chattering hangovers. New bands rise out of the Dolls–Stooges–Velvets–Modern Lovers matrix: the almighty Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads. At CBGB, he finds Ramones clones onstage while the real Ramones play pool in back. A Baudelaire quote serves as art-party confetti: “Dandyism is the last burst of heroism in the midst of decadence.” Whee! But decadence, rust-like in its sleeplessness, creeps into the young like early-onset osteoporosis. By the fall of 1975, his entries start to lose momentum, and his evocative lists of movies and albums and books gradually dry up. Twentieth—Century Boy holds interest right through his growing divestment and disenchantment, but over those last hundred pages it is the story of a man in search of an exit strategy.

In 1977, a newly minted teenage aesthete myself, I was introduced to Television’s Marquee Moon via a subscription to the Village Voice. I remember the lightning-bolt tingle from critic Ken Emerson’s juxtaposition of a Joseph Conrad quote (“In the destructive element immerse”) with a lyric from the album’s opener, “See No Evil”: “I get ideas / I get a notion / I want a nice little boat / Made out of ocean.” Before I’d heard a note from the band, I was hooked. Ah, the crummy glamour of self-aggrandizing losers! Compartmentalization is always a tricky business, especially for those wild twentieth-century boys and girls who sought to make their lifeboats “out of ocean.” For Hannah and his cohort, it was a survival tool taken from a manual in which self-destruction and self-creation came under the same heading. As his abandoned title suggests, these journals are riveting cautionary tales, demonstrating the necessity of raw experimentation as a source of discovery and creativity, uneasily coupled with the steeply diminishing returns of losing control as a way of life—or art.

Howard Hampton is a frequent contributor to Bookforum and the author of Born in Flames: Termite Dreams, Dialectical Fairy Tales, and Pop Apocalypses (Harvard University Press, 2007).