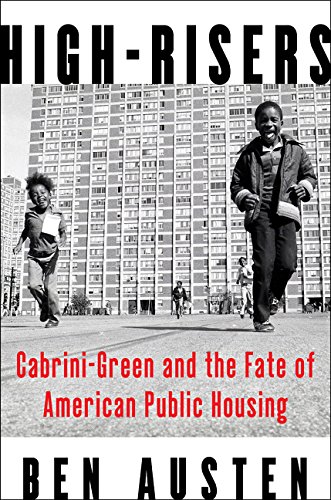

By the time the last tower at Cabrini-Green was demolished, in 2011, the notorious Chicago public-housing complex had become a national shorthand for anything “derelict or dangerous, from neighborhoods in other cities to a temporarily out-of-service elevator in a high-end apartment building,” as Ben Austen writes. In his new book, High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing, Austen explains how the homes, built between 1942 and 1962, started out as a vision of what public housing could be and ended as an example of inner-city blight.

Plenty has been written about the Chicago Housing Authority’s dismal track record. But Austen brings something new to the table. A detailed, warm, and clear-eyed work of literary nonfiction, High-Risers is invaluable for anyone seeking to understand public housing’s past and brace for its future. Like Matthew Desmond’s Evicted and Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, it deepens our knowledge of public housing in America, and reveals just how little we understood about it in the first place.

High-Risers avoids both rosy revisionism and tawdry sensationalism. Interweaving accounts of residents’ lives with discussions of the housing policies, local politics, and cultural shifts that led to the decline of Cabrini-Green, High-Risers invites readers to hold two opposing facts in mind: first, that life in Cabrini-Green was difficult and dangerous; and second, that those who lived there wanted the world to know that their infamous housing complex could still be a home they trusted and chose.

As we read about the violence and neglect—and government policies that made both possible—we come to understand why many of these tenants fought to remain in their homes as the housing project was demolished, tower by tower. Pointing to the strong community bonds they had forged over generations, some residents refused to leave when they had the chance. “I’m in the projects, but that’s my home,” said Dolores Wilson, the matriarch of one of the first families to move into the newly built towers in 1956.“I love my home, just like you love your home.”

The denizens of Cabrini-Green, we learn, organized pickup football games and picnics. They fielded the nation’s largest Boy Scout troop. Like Dolores Wilson, many of them loved living there. Yet they were dealt an unconscionable hand by the government, which was supposed to help maintain their homes and community.

Violence, of course, can happen anywhere. But High-Risers makes clear that Chicago’s public-housing residents, especially the children, were more likely to experience it firsthand. Veronica McIntosh, a thirteen-year-old Cabrini-Green resident, was kidnapped by a security guard and repeatedly raped in the back seat of his car. Rodnell Dennis, also thirteen years old, joined a gang and murdered a nine-year-old. Dennis was tried as an adult and sentenced to nearly forty years in prison. Dantrell Davis was seven when he was shot while walking to the school just across the street from his building. Davis’s killing was one of the few deaths at Cabrini-Green that caught the attention of those in power.

Even when news of life at Cabrini-Green reached the surrounding city and suburbs, there was little interest in understanding public housing as anything but a drain on resources. By the 1990s, the widespread belief that the condition of public housing was the result of a moral failure of its residents, rather than the result of municipal neglect, geographic segregation, and job loss, had thwarted more meaningful reforms. “Fewer and fewer Americans believed they had a collective responsibility to provide enough for those who had too little,” Austen writes. “Most serious debate about inner cities, social services, and housing subsidies gave way to tough talk of police, prisons, and demolition.” Across the country, the message was clear: Crack down and tear down.

Though Austen doesn’t discuss the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program—the federal initiative launched in 2012 that privatizes public housing, in order to preserve and rehab decaying units—High-Risers obliquely shows the plan’s hidden pitfalls. Given the federal government’s stubborn refusal to adequately fund public housing, RAD might indeed be the most politically viable way to save the affordable units over the long term. But as history reveals, plans to privatize public services can backfire, and often do.

At least sixty thousand public-housing units across the country have been transferred into the private sector through rad since the program started. Almost a fifth of those conversions have taken place in RAD. But tenants are justifiably anxious they’ll end up with even less while being forced to pay more. Austen’s book helps us to see why. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Cabrini-Green tenants balked at being moved into “mixed-income” buildings with resentful condo owners, as well as at the meager Section 8 benefits some received, on which they could afford homes only in neighborhoods worse than the one they’d left. Following the successive evictions and displacements that many public-housing residents suffered during the federal government’s and Chicago’s respective “urban revitalization” programs, it is not surprising that they would feel deep ambivalence about further change.

High-Risers is ultimately less about “the fate of American public housing,” as its title claims, than about the fate of Cabrini-Green. True, the now-demolished development can be seen as representative of Chicago’s public housing in general; even so, the book doesn’t go into much detail about public housing’s present and future in the Windy City. Nor does Austen present specific policy proposals in his conclusion. Instead, High-Risers leaves behind a visceral sense that the housing system has failed too many. Millions live in segregated, impoverished communities and many more are unable to afford safe and durable shelter. High-Risers punctures our collective indifference, but moral reckoning alone is not enough.

Rachel M. Cohen is a freelance journalist based in Washington, DC, and a contributing writer to The Intercept. Her work has appeared in the American Prospect, Slate, and Vice.