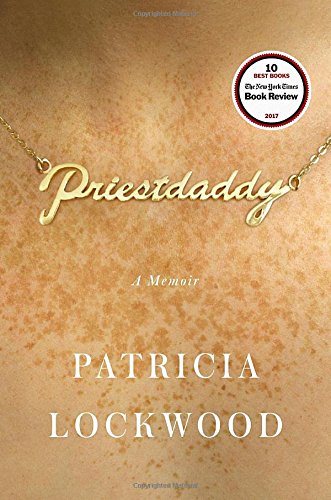

I teach memoir writing, and occasionally my students want to learn how to be funny, which fills me with despair. There are many great memoirs—The Liars’ Club, Wild, Autobiography of a Face, Shot in the Heart, The Kiss—and hardly any of them are funny. Real-life tales of suffering, endurance, recovery, emotional survivalism—these are the generally established plotlines for contemporary memoir, what allow writers to indulge literary egocentrism for 280 pages, and what allow readers to be pain voyeurs in a safe, temporary environment. Happily, there are exceptions.Poet Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy (Riverhead, $27) is one.

The author is the child of one of only 120 American Catholic priests who received papal dispensation from the celibacy requirement, and Priestdaddy is in part a memoir about growing up in the inner sanctum of the Catholic Church. On its release, Lockwood was widely labeled “millennial” (a broad, nonliterary descriptor), because her memoir is framed by the eight months that she and her husband lived with her parents in the wake of a medical situation/financial setback, and because Lockwood is a Twitter artist. “Free in the knowledge that no one was listening,” explains Lockwood, “I mostly used it to tweet absurdities like ‘ “Touch it,” Mr. Quiddity moaned. “Touch Mr. Quiddity’s thing.” ’ ” Lockwood’s tweeting isn’t entirely ornamental; she uses it to raise money for the medical situation, and it’s the means by which the poem “Rape Joke,” which she published in the online magazine The Awl, went viral. The event led to a poetry-book contract with a major trade publisher, followed by this memoir—a remarkable career trajectory for a poet.

Priestdaddy is an emotionally candid book but doesn’t stink of dirty laundry or even oversharing. Lockwood doesn’t participate in her family’s faith and isn’t remotely doctrinaire about religion. This is a memoir made up of conversations, musings, scattered childhood memories (which tend to the emblematic rather than the formative or linear), and ranging, pungent observations. “To write about your mother and father is to tell the story of your own close call, to count all the ways you never should have existed.” Despite references to molester priests, cultish teenage youth groups, anti-abortion protests, and her own date rape, the most thrilling and memorable scenes are of her learning to swim, peeing in the back of a moving van, and discovering semen crusts on her hotel-room linens.

Internet addiction as sin is as close as a reader gets to the implied promise that there is a dark underbelly to being a priest’s daughter. Casual banter between Lockwood and her mother is the source of the book’s most religious material; it is absurd, feverishly rhetorical, and endlessly charming:

“Tweeting is an art form,” I told her. “Like sculpture, or honking the national anthem under your armpit.”

“It’s not art if it’s evil,” she said.

“It’s only art if it’s evil, Mom.”

Her storytelling mode moves between slapstick and deeply impressionistic. The great scarring life events—those that typically shape a memoir—are played for laughs or woven into a crazy quilt that privileges the ways in which her world is at once unique and benign in the grander scheme. Her father isn’t “Catholicism,” or even, for that matter, the “priesthood”; he’s a snowflake, replete with facets and holes, no more or less a father, man, or priest than he is. “Please give me something, anything: a crumb of the bread that you stand in front of the people and change,” implores the memoirist, her notepad at the ready, “but whole Bibles have been written about the man who wasn’t there, who appeared for some and never others.” Lockwood’s priestdaddy remains a conspicuous enigma, neither a charismatic nor a threat—a priest in his vestments tending his flock, also a man in threadbare boxers holed up in his room with his TV and electric guitar. He’s in many ways an inattentive father, whose own fascinations are so different from Lockwood’s that the fact of him being a Catholic priest is more circumstance than the center of her memoir.

Lockwood’s mother instead dominates. She is resolutely illogical, absolutely capable, and enviably devoted:

“According to a website I was reading about gators who kill, more and more gators are becoming killers. One gator, they opened him up, and they found twenty-two dog collars inside.”

A pause.

“Mom, that doesn’t sound . . .”

“No, it doesn’t sound real at all, now that I say it out loud.”

“Is your head just full of things like . . . gator killers . . . we swallow seven spiders every night . . . rainbow parties and jenkem . . . money is covered with cocaine . . . a dangerous new game called ‘chubby bunny’ . . . men hide under cars in mall parking lots and slash your ankles with a razor when you walk by . . . Satanists have a new plan to eat the pope . . .”

“Promise me one thing, Tricia,” she begs me. “Promise me you will never play that deadly game called Chubby Bunny.”

In such spirited moments, Priestdaddy has more in common with Clarence Day’s 1935 classic Life with Father, or, perversely, one of Erma Bombeck’s cheerful dispatches from suburban-housewife drudgery (best sellers in the 1970s and impossibly dated now), than it does with The Liars’ Club or Wild. Unlike the high-stakes tragedy-porn memoir that’s been winning readers’ hearts the past quarter-century, Priestdaddy is distinctly not haunted, not traumacentric. As if ushering us into a new phase, Lockwood pushes her memoir past the PTSD of Generation X, back into a world where dysfunctional families are zany instead of traumatizing. The result is both comforting and bewildering, progressive and somehow backward-looking at once. Maybe that’s exactly the kind of liminal mode this moment of extreme cultural schism begs for, where politics, generational leaps, and even ethics put loving families on opposite sides of big issues. If you can’t win an argument, your next best option is to laugh at it.

Minna Zallman Proctor is the author of Landslide: True Stories (Catapult, 2017).