There will be people who visit you in prison, and who watch over you at first when you come out. They will try to help you, but unless they truly understand your lot, understanding your goodness as well as your badness, and sympathising with your badness as well as with your goodness, they will seem far off from you. Who knows, though, but what you may help them?

—Constance Lytton, from Prisons & Prisoners: Some Personal Experiences (1914)

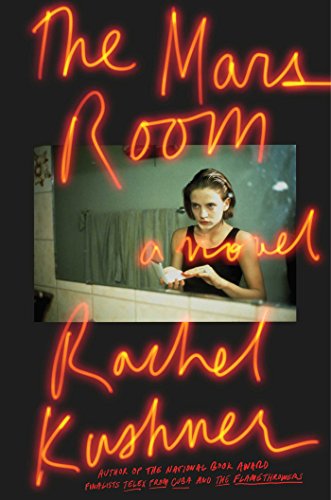

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN you’re removed from the scrum of history, when you can’t change anything beyond your immediate experience? That’s one of the questions wiring The Mars Room, Rachel Kushner’s third novel. Her first two novels swim in historical events—Telex from Cuba finds two Americans riding the wave of Castro’s ascension, and The Flamethrowers maps one American artist’s flight through the clouds of Italy and New York in the 1970s—but The Mars Room boils history down to a nubbin.

Romy Hall, a former stripper, receives two consecutive life sentences for killing her stalker, and is sent to the Stanville Women’s Correctional Facility in the Central Valley of California. The action takes place around the invasion of Iraq in 2003, which many of the inmates are only dimly aware of. (Romy’s cellmate Sammy confesses she knows more about Friends than the war.) When larger movements like war are blocked from view, the daily handoffs and scuffles of family—blood and state-issue both—are what remain. The deals you’ve made to live determine your cohort and define the smaller histories you can adjust.

Agents of speed animate Kushner’s work: Italian engines, convulsing islands, compressed information. This tendency contains its own marginal utility problem. Go fast enough and you get used to going fast. Go fast enough and the machine slows down. Go fast enough for long enough and you’ll run out of fast. Chemical speed, physical speed, and mental speed are all preludes to the comedown, a feeling Kushner masters in The Mars Room, a gorgeous, contemplative slow ride after two burners. What’s slower than prison?

The cars and motorcycles of The Flamethrowers are replaced by one big bus traveling up the middle of California from county jail to state prison. It’s the first scene of The Mars Room, an establishing shot. The women are handcuffed passengers, being driven past Six Flags Magic Mountain in Valencia, unable to do more than slump when it’s time to sleep. As she rides, Romy’s vision is as constrained as her limbs, and she slips into paranoia. She sees black shadows on the side of the road and thinks they’re “huge black clouds of smoke or poison.” A moment later, she knows she’s just dramatizing a bus ride. “They were the silhouettes of eucalyptus trees in the dark. Not an emergency. Not the apocalypse. Just trees.”

Incarcerated or not, the first person you make a deal with is yourself. Early on, while being held in county jail, Romy adopted an approach to her existence in prison. “It was my first night in jail and I kept hoping the dreamlike state of my situation would break, that I would wake up from it.” She cried uncontrollably, until another woman in the cell shook her and pointed to the tattoo on her lower back: Shut the Fuck Up. “It was a gentle moment with my cellmate in county.” Romy quit crying. She now considers this woman “a kind of saint. Not for the tattoo but the loyalty to the mandate.”

This is how The Mars Room finds the universal without a backdrop of big social eruptions. Good People do not encounter difficult situations and earn Valuable Wisdom. The telos here is not moments of epiphany and improvement but a kind of spiritual pragmatism that plays the same inside and out. Everyone needs to hear “Shut the Fuck Up” clearly, at least once.

Stripped of world historical forces and their halo, the novel has to focus on the tighter circles of family and work. The companies here are the strip club and Stanville. In the previous novels, men in uniform come from elsewhere, but in The Mars Room, the dipshits of control are in the same building as the protagonists: prison guards too lazy to move from their towers, bouncers too callous to get the story straight. (In a book long on empathy and short on scorn, the only subset to really get the boot from Kushner is men who are paid to sit.) The emotional compression of family is mimicked by both workplaces, neither of them normative (unless making sandbags for the state is normative, which it probably is). The slow torque of the book embodies the limited range of the imprisoned being multiplied by the infinity of a life sentence. The Mars Room uses a handful of years behind bars as the fixed hub of the present, and Romy’s memories become the spokes.

Before Romy landed in prison, her youth was relatively benign if unmoored, and she dabbled with lawlessness because it was there. She grew up in the Sunset District of San Francisco, a town she doesn’t like as either a present or past. With little fanfare or hand-wringing, Romy describes a period spent largely on drugs and hanging out until it was time to take more drugs. With the Golden Gate Bridge in view, she and her friends navigated their own chaos. “Someone holding a loaded gun to my head for no reason in Big Rec, where people play baseball in the park,” Romy recalls. “It was night, and this psycho attached himself to us while we were sitting and drinking our forties, a situation so typical, even if it never happened again, that I don’t recall how it resolved itself.” Romy’s friends drifted through houses—one of them a place where the ungoogleable Scummerz have squatted and decorated an entire room using only tennis balls soaked in paint. Some kids liked going to Anton LaVey’s house, which doesn’t suit Romy. “You had to be from a conventional background to go full tilt into devil worship.” She’s got punch lines.

Romy finds a somewhat benign and unmoored boyfriend named Jimmy Darling, who gives good car. “As a teenager Jimmy Darling worked at an auto glass company. He told me that the first time he smelled the adhesive that was used to glue auto glass in place, he realized that he had dreamed of that very smell, the smell of that particular glue, and that it was his destiny to work replacing auto glass.” She works at the Mars Room, a San Francisco strip club whose lack of discipline serves as a loose narrative antipode to prison. “At the Mars Room, I did not have to show up on time, or smile, or obey any rules, or think of most men as anything other than losers to be exploited but who believed they were exploiting us, and so it was naturally quite hostile as an environment, even as it was coated in pretend submission—our own. The Mars Room was a place where you could do what you wanted; at least I had believed that.”

There aren’t so many plans to make at Stanville, so Romy reviews the path that brought her to the Mars Room, where her stalker, Kurt Kennedy, latched on. Her take on the past is stubbornly uncolored. “I don’t miss those years,” she deadpans after recounting the first time someone shot her up with morphine. “I’m just telling you.” Romy is equally unimpressed by death row. “Death row was underneath us, in the same building. The cops call them ‘grade A.’ They say it about fifty times a day and probably the prison administration thought it was bad for staff morale to say ‘death row’ over and over.” The only person who can make Romy drop her armor is her son Jackson, who lives with Romy’s German mother. It is typical of Romy’s blend of equanimity and curiosity that she doesn’t seem all that mad at her mother, who neglected her as a kid, though in a fairly passive way. When Jimmy Darling asks why Romy doesn’t speak German, she doesn’t feel regret or anger. The bemusement she does feel may be the root of her deep resilience. “The idea of my mother teaching me German had never occurred to me. The idea of her teaching me anything was difficult to imagine.”

MICHEL FOUCAULT’S “LIVES OF INFAMOUS MEN” rings out over Stanville. The introduction to a book that was never completed, Foucault’s essay details his fascination with legal documents from the early eighteenth century. The texts he collected were both descriptions of the person being imprisoned and lists of the crimes that led them to prison—“seditious apostate friar, capable of the greatest crimes, sodomite, atheist if that were possible.” As Foucault writes about these subjects: “So that it is doubtless impossible to ever grasp them again in themselves, as they might have been ‘in a free state’; they can no longer be separated out from the declamations, the tactical biases, the obligatory lies that power games and power relations presuppose.”

Romy’s prison family stays the same for the entire book, replacing the declamations of the state, every day, with their own. Betty LaFrance, former leg model for Hanes, is on death row for hiring one too many hit men. A celebrity of sorts, she is obsessed with her own story, which she constantly fact-checks. When another inmate says Betty hired a security guard at the El Cortez casino to kill a cop, she jumps in. “‘Honey, it was NOT the El Cortez,’ Betty yelled up the vent. ‘It was Caesars Palace. And honestly, if you’re going to tell my story and you don’t know the difference between Caesars Palace and the El Cortez, there is just so much else you can’t know.’” The prisoners negotiate their stories much as anyone else does; their audience is just smaller. Laura Lipp killed her baby, but Romy doesn’t like her because she won’t shut up; Conan looks exactly like a man, so much so that she was sent to the men’s prison briefly; and Romy’s roommate Sammy Fernandez has been rotating through the system for much of her life. When the short emotional cables of family and granular physical detail combine, The Mars Room sings.

After disobeying a guard’s orders, Romy and Sammy are put in “administrative segregation,” right above death row. Betty is still good at manipulating dipshits in control; she makes hooch in her cell and manages to lay her hands on a pair of stiletto heels. “She paid a cop hundreds to smuggle them in, just so she could put them on now and again and admire her own legs.” The hooch is called “pruno,” and she shares it with Romy and Sammy, through the plumbing. “She made it the usual way, with juice boxes poured into a plastic bag and mixed with ketchup packets, as sugar. A sock stuffed with bread, the yeast, was placed in the bag for several days of fermentation.”

History winds around The Mars Room without ever breaking through the window. Gordon Hauser is a well-intentioned academic who ends up teaching at Stanville. It seems like an OK job, with a few chances to become useful. At first, Romy needs Gordon and his access to the outside world. When she finds out her son Jackson is in peril but that she’s lost her status as primary caregiver, Gordon is the only person she can ask to track him down. Just as Romy tries to enlist Gordon, he realizes that the prisoners often try to use him. He’s participating in his own submission.

Gordon lives in an isolated hill cabin, so a friend gives him Ted Kaczynski’s diaries—a joke that doesn’t read like a joke. Both Gordon and Kaczynski are isolated skeptics. Gordon is trying to make a sort of difference within the system, while the Unabomber has abandoned it entirely, destroying vehicles and killing scientists in the hopes of pushing back the Industrial Revolution. (Doesn’t work.)

There are five excerpts from the Unabomber diaries spread through the book. It’s not a spoiler to reveal that there is no Unabomber in Stanville and Gordon doesn’t make Kaczynski his hero. But Kaczynski’s impulses float through the book and animate Gordon’s sections. When he looks at the land that stretches from his hill cabin to the prison, he more or less sees Kaczynski’s view of nature as something that degrades as you add people to it. Before describing the valley and its almond farms as a “brutal, flat, machined landscape,” Gordon drinks in the land around his home, far from civilization.

He never saw a mountain lion, only heard them. In the early morning, on his way down the mountain toward Stanville, he sometimes glimpsed gray foxes, their lustrous tails trailing after them, as he followed the curves of the winding road, passing huge drought-desiccated live oak, their jagged little leaves coated in dust, and banks of rust-red buckeye and smoke-green manzanita. The buckeye branches without leaves glinted bone-white in the sun. The grasses were the rich yellow of wet straw. He’d never seen such beautiful grasses.

The cadence of The Mars Room is fluid throughout, as intense as the dense circuitry of The Flamethrowers, just cooler.

In the final third of the book, the line pulls taut as all the spare language begins to fly. The story draws to a point and you find out why the words need room to move. One of the hit men Betty hires and subsequently tries to eliminate, a crooked cop named Doc, shows up on the Sensitive Needs Unit in New Folsom prison. He is trying unsuccessfully to avoid conflict in a place that hates cops axiomatically, while occasionally missing Betty. (Doesn’t work.) The strongest and least expected familial tie between characters comes when we finally get a flashback from Kurt Kennedy, the stalker who chased Romy from San Francisco to Los Angeles and menaced her right into murder. We pick him up drunk out of his mind on an airplane, thinking about Vanessa (Romy’s stage name at the Mars Room). His reasons for allowing himself to obsess over Vanessa are circular and existential: “When he was near her, he felt good. Every person deserves to feel good. Especially him, since he was himself.” He mists the plane with pathos.

There was a couple next to him turned inward to each other like they didn’t really want to talk but he tried anyway. Sometimes shooting the breeze with people kills time. He told them about his boat and he didn’t actually have a boat but he’d been talking for so long like he did have a boat that he basically, at this point, owned a boat. But they weren’t interested.

Kurt has the freedom to drift and, with the careless help of a doorman named Jimmy the Beard, tracks down Romy in LA after she’s fled San Francisco. Until his last moments, sitting on her porch, he is himself, unable to see his actions as anything other than what he had to do. Kennedy’s encounter with Romy, and the buildup, is the speed trial you absolutely don’t expect, and it hits hard. The last thirty pages of the book are pure energy, a sharp upward kick. Kushner doesn’t disavow speed (or vehicles)—she just makes you wait for it this time.

When Romy makes her big decision, she ends up covering Kurt Kennedy’s song. “Yes I think I’m special. That’s on account of me being myself.” When she says it, she is as free as she ever is. It doesn’t last.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer and musician from New York.