PICTURE THE CAREFREE SWAGGER of a teenage white boy, shirtless and smooth, swinging himself into a pristine tree-lined body of water from a rope as if there were no history, no context, no world. Instead, simply the body and the self it manages, flying gracefully with no net, nothing to carry that body to safety but its own faith that nothing will squash it down. My dear friend Ronaldo Wilson, a beautiful, brilliant queer black man whom I met at the Cave Canem Retreat for African American Poets almost twenty years ago, might call this state of swagger and swing with no history “neutral innocence.” “There are those of us who will never even approach the experience of neutral innocence,” he once said. This neutral innocence comes about from whiteness, but it is also gendered, and very male. I cried out of sheer desire for this body while watching the confident, curious young man in Luca Guadagnino’s film Call Me by Your Name. What a distance, I thought, what a galaxy away from the black experience in America.

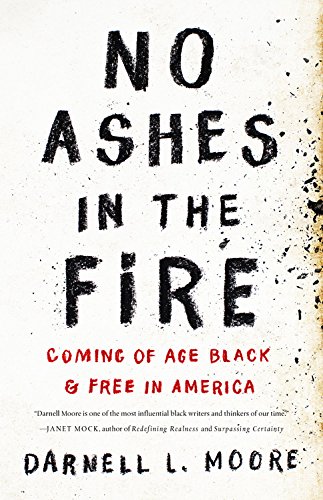

In When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir, by Patrisse Khan-Cullors and asha bandele, and in No Ashes in the Fire: Coming of Age Black & Free in America, by Darnell L. Moore, also a Black Lives Matter activist, the very idea of neutral innocence is a sword in the shoulders of black people. Vaunting its privilege through its comfortable unawareness, it serves to weaken, to disable, to bring to their knees the one who succumbs, so when the final, fatal slice occurs, the kneeled body has open eyes, is aware. In between the first stab of the knife and the last is the space where radical hope lives.

Both Khan-Cullors and Moore inhabit radical hope so fiercely and bravely that it seems almost impossible. These memoirs chart journeys from poverty and state violence against black people—for the affront, as Khan-Cullors says, of simply “being alive”—to empowered activism and social change. After a jury acquits Trayvon Martin’s killer George Zimmerman of all charges, Khan-Cullors, in a grief-stricken Facebook collaboration with Alicia Garza, coins the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. This is the moment that redefines what it means to do black intersectional activism in the internet age. Khan-Cullors develops her strategic and analytical skills at the Labor Community Strategy Center in Los Angeles—a “think tank/act tank” that focuses its campaigns on improving the lives of working-class communities of color. It’s this groundwork that will inform the longer Black Lives Matter moment.

Moore, a writer, social justice organizer, and Princeton-trained theologian, joins Black Lives Matter after eighteen-year-old Michael Brown is shot to death by police and Khan-Cullors and her crew decide to organize a Freedom Ride to Ferguson. This is where Khan-Cullors’s and Moore’s narratives intersect. Organizers from different parts of the country, restless and angry in the wake of yet another killing of an unarmed black person, are pulled to Ferguson (at that moment occupied by a militarized police force) in the fight for justice.

Khan-Cullors tells the story, with help from her coauthor, the writer asha bandele, of growing up poor and black and a Jehovah’s Witness in Van Nuys, California, in the 1980s. Khan-Cullors’s mother, Cherice, was raised in a middle-class family but was “disfellowshipped” from the congregation for fornication outside of marriage, catapulting Cherice and her children into deep poverty and community isolation. In their section of Van Nuys, the family gets a vicious education in how black people, from childhood on up, are surveilled, disciplined, and brutalized by the police and other institutional regimes—in particular, that Reagan-era treat “the War on Drugs”—that bolster white supremacy in the name of law and order.

When They Call You a Terrorist takes a hard, painful look at this war through the lived experiences of Khan-Cullors and her family. Her brothers, Monte and Paul, and their friends, who are all under fifteen years old, are routinely roughed up by police, thrown to the ground and humiliated, for walking, talking, gathering, or “doing absolutely nothing.” Patrisse herself is arrested when she is just twelve years old. A cop comes to her summer-school classroom, assuming she has drugs. He doesn’t just pull her outside the room to ask her if she has any of the weed he thinks she does; he handcuffs her in front of the class. Later, her beloved brother Monte is disappeared by police after being charged with attempted robbery. It turns out Monte has a mental illness. Instead of properly medicating him, “they beat him and they kept water from him and they tied him down, four-points hold, and they drugged him nearly out of existence.” When they release him, years later, they do so without giving him any clothes. He exits the bus, writes Khan-Cullors, wearing “a thin muscle shirt and a pair of boxer shorts.”

These experiences inform Khan-Cullors’s activism as an adult. Seeing black people constantly jailed brings her to an understanding of how, when society orients itself toward safety, darker-skinned people become the scapegoats. Describing her work to dismantle what’s known as the “school-to-prison pipeline” she notes that after the Columbine shooting, which occurred in a mostly white school, “Black and Brown kids across the country got police in their schools, complete with drug-sniffing dogs, bars on the windows and metal detectors.” The result was more children getting scooped up by the criminal justice system. Khan-Cullors narrates this difference with precision, as she notes the radical divergence between the open green space at the primarily white middle school she traveled to attend and the cage-like conditions that define the public space in her own neighborhood.

Khan-Cullors’s memoir is gorgeously nonlinear. She tells her story in the voice of the clear-eyed analytical adult, as if responding to the very relevant question “How did I get here, you ask?” with, “Well, let me tell you.” Memoir is a tricky genre: It narrates both a particular set of linked occurrences andan ongoingness indicating that similar things have happened across time. By juxtaposing Khan-Cullors’s childhood memories with the activism to which she has devoted her adult life, the memoir gives us the events as well as their social and historical contexts. In one scene, she describes hiding as a child as she watches her brothers get violated by the police:

They throw them up on the wall. They make them pull their shirts up. They make them turn out their pockets. They roughly touch my brothers’ bodies, even their privates, while from behind the gate, I watch, frozen. I cannot cry or scream. I cannot breathe and I cannot hear anything.

A few paragraphs later she writes, “I will not think of this particular incident until years and years later, when the reports about Mike Brown start flowing out of Ferguson, Missouri.” The foreshadowing here is pristine, tying these two moments together, and making us feel the attack on black people as if time has stood still.

Darnell Moore’s No Ashes in the Fire is set on the other side of the country, in Camden, New Jersey. His young parents are trying to raise him, but his dad is a cauldron of rage who severely beats Moore’s mother with, it seems, regularity. Darnell is nine years old the first time he sees his father assail his mother. No Ashes in the Fire is saturated with male violence, just as it is with state-sponsored violence. The violence inflicted by the state, Moore clearly contends, is what produces other violence in his community. Protection is hard to come by. Black people are the assumed threat. Everyone is forced to do whatever it takes to create their own means toward survival in a society that strategically props itself up on our backs.

No Ashes in the Fire illuminates the fragility of black life no matter how much love surrounds it. As he grapples with social tragedy and the insecurity of black masculinity, Moore displays magnificent self-reflection. He narrates his story in a looping, lyrical style that approaches complicated truths through metaphor. When he talks about his father’s troubled affection for him, he writes: “The love was deep, but its tides weren’t so violent as to cause me to drown.” Lyricism lifts the comparison here and brings us close to this difficult love that might otherwise be raw anger.

Framed as a kind of investigation of home, Moore’s memoir traces the history of dispossession and displacement beneath his family’s poverty. His great-grandmother Elpernia, who lived, when Moore was a kid, in a government-subsidized town house, lost the house she once owned to foreclosure:

My family mastered the art of locking away secrets. I searched digital archives to learn my great-grandmother’s maiden name, the names of her parents, her date and place of birth, and the date she lost her home. I searched because I wanted to understand my family’s history—my history. Stumbling through the present unaware of the people and circumstances from which I came was like walking in the dark.

The opening chapter, titled “Passage,” sets the stage for what will become the primary location of Moore’s deep study of his family’s history, his history, and—most importantly for the activist he will later become—the history of what structural race discrimination has wrought and how it works. The whole of South Camden, where Moore’s family lives, stinks because it’s located near the county’s trash incinerator plant and the city’s waste management facilities. “The trash incinerator,” Moore states baldly, “was built in Camden because it was a predominantly black and Latino city.” From this setting, Moore attempts to pierce the hazy stench that permeates Camden’s air, in order to find some room to breathe.

For Moore, these efforts often take the form of an empathy that borders on the transcendent. In a particularly ghastly scene, a neighborhood bully named OB douses Darnell with gasoline while he is walking home, and attempts to set him on fire. OB calls Darnell a “faggot” and appears enraged. Other teenage boys watch. When the matches don’t light, OB begins to punch and kick Darnell. He is eventually rescued by his aunt Barbara, who fights OB and his enablers off. Darnell lands in the emergency room, badly beaten and still flammable. He is fourteen. Although this is an anchor moment of abuse that defines his story, he turns away from his own pain and toward the pain of his attacker. Moore writes, “I knew the immense poverty he and his siblings endured, and I knew that the violence that had become mundane in our neighborhood had begun to shape him in the same ways it had started to shape me.” This movement from the violence committed by another, to the structural racism at work, and then back toward the self is a dynamic that Moore will employ many times in his narrative. No one is safe. No one is presumed neutral or innocent. The author does not presume himself to be.

I think he’s being too hard on himself, though Moore’s taking good looks at his own actions does provide us with a way of knowing his character. He refuses to accept a narrative of victimhood—that somehow, in all the mess of it, he emerged blameless and untouched by the rigorous assault on black life. OB’s attack, and the hypermasculinity that upheld it, is present throughout Moore’s story as an undercurrent of fear, obstructing and prolonging his coming-out process and his own acceptance of his sexual orientation. “Queerness,” he admits at a different moment, “is a way of life people fear because in it they might find freedom. But I was caged for a long time before I took hold of my liberation.”

That both Khan-Cullors and Moore are queer is central to their stories. For both authors, it creates a breach between them and the worlds they know. What saves Moore—or, more pointedly, what allows him to save himself—is his queerness, what he calls “the magic expressing itself in and through my black body.” Queerness provides him a slanted way of looking at the world. Because of it, he is always insider and outsider in his neighborhood, straddling multiple realities, one toe positioned in another country. Queerness shapes the platform Khan-Cullors helps develop for Black Lives Matter, and it informs her imagination of a possible new world in which we feel that we are, in fact, “made of stardust,” as she writes in her prologue.

When Moore writes of the “dance battles my mom and aunts held in our living room . . . as lively as any on Soul Train,” I think of the euphoric sanctuary of dance at a gay club, music pumping through our queer bodies, sweat soaking our clothes until we take them off in the heat of close-up movement and claustrophobic exhalation. At Pride NYC in 2016, only weeks after the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, I went dancing at a packed club in Brooklyn and experienced exactly this kind of exultation. It was a refusal in the face of what appeared daunting. It was a refusal to lie down and be still. That refusal was joy. Neutral innocence is in the queer dancing hearts of these authors’ stories, even if in the American world the black body is often viewed as a monstrosity, and this is what distinguishes their particular models of organizing for black life.

Dawn Lundy Martin is a poet and essayist whose latest work appears in n+1, Harper’s, and the New Yorker.