I spent some time on the campaign trail in 2016, and one thing that struck me about the genuine Trump supporters I met was that they seemed to be full of shit. The pronouncements they made were empty: that the Constitution would be imperiled if Donald Trump lost, that his defeat would spell the “end of America,” slogans they seemed to have picked up from fringe websites or AM radio stations. It was the enthusiasm of the sports fan. Of course, there were other sorts of voters on the Trump train. Casual and virulent racists, accessorized with Confederate battle flag pins. The chauvinist Apprentice devotee who gestured toward his crotch, said we needed a president with “a pair of these,” and compared illegal immigration to throwing a dinner party where you wanted to eat spaghetti and the guests demanded burritos.

In New Hampshire I met a schoolteacher who was indoctrinating a set of tweens in the evils of political correctness. At the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, I met an intellectual property lawyer who seemed neither to like Trump nor to hate Clinton; he insisted that the Republicans were looser and quicker when it came to issuing patents, they didn’t get bogged down in negotiations with the EU, and that’s what really creates jobs and makes the economy thrive. In Elkhorn, Wisconsin, the day after the release of the Access Hollywood tape, at a rally where Trump had been disinvited by Paul Ryan, there was a set of adults wearing deplorables T-shirts, all of them dismissing their candidate’s remarks as “locker-room talk.” But there were others who didn’t fit the caricature, much less flaunt it. One young woman who wouldn’t have seemed out of place at a house party in Brooklyn told me, “I think what he said is wrong, but I don’t like Hillary Clinton’s plan for the country.” Then there was my father, a retired truck driver who spends most of his time taking care of his elderly neighbors. He voted for Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary and Trump in the general: “Everybody has their reasons. Mine is the Clinton Foundation.” I know him well enough to know that his understanding of the foundation’s fund-raising and works isn’t very sophisticated. As he said just before the election, “I made up my mind and stopped paying attention a couple months ago.” As in most years, he voted for a candidate, like Ralph Nader, who he thought would lose. He wasn’t the only one who thought so.

Two years on, the 2016 election is the most overexamined and least understood event in recent history. The distortion field created by the Trump administration itself, the Mueller investigation, and speculation about the existence of a video of the future president watching prostitutes urinating on a hotel bed haven’t clarified matters. Was America the mark of an all-consuming nefarious foreign plot, or did Clinton simply neglect to visit Michigan and Wisconsin at the crucial moment? Did ingeniously and intrusively placed advertisements on social media tilt a vulnerable electorate, or was it the habit of cable network morning shows to allow the Republican candidate to call in on a daily basis and ramble at his pleasure? Did Bernie Sanders mortally wound his primary opponent, or would Bernie have won? Are 63 million American voters irredeemable racists, or had they simply had enough of Hillary Clinton?

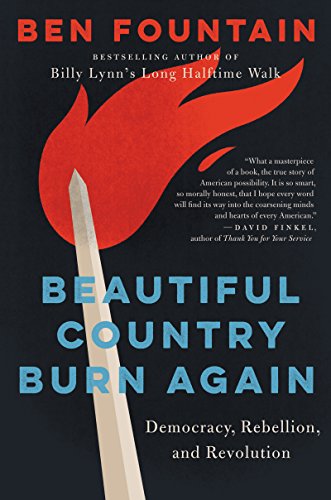

Ben Fountain’s new book Beautiful Country Burn Again doesn’t exactly answer these questions, but it brings us back to that deranged year and restores a sense of what our politics felt like at the time. Fountain is sixty years old, grew up in North Carolina, and lives in Dallas, where he was briefly a real estate lawyer until the age of thirty, when he quit to become a full-time fiction writer. He is famously one of the specimens in Malcolm Gladwell’s theory that it takes ten thousand hours of practice to master a discipline. His acclaimed short story collection Brief Encounters with Che Guevara appeared in 2006, and his pro-troops, anti-war novel Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk in 2012. In 2016 he wrote a monthly column for The Guardian about the US election. These essays, which combine on-the-spot reporting with historical commentary, leaning heavily toward the latter, form the bulk of Beautiful Country Burn Again, but they have been revised, in some cases quite heavily, in light of the results. Nonetheless, the emphasis remains on the candidates as we saw them then. Clinton isn’t the folk heroine martyr she’s become to some. Trump isn’t a shadowy Russian agent but a blowhard who picks fights with Fox News and asks a crowd in Iowa, “Why would I denounce Putin for saying I’m a genius?”

Conservative Political Action

Conference, Fort Washington,

Maryland, 2017.

Fiction writers and poets turned in some of the most memorable journalism of the campaign cycle. A roll call would include essays by Patricia Lockwood (on Trump), Clancy Martin (Ted Cruz), George Saunders (Trump), and Joshua Cohen (Sanders, Trump). These reports tended toward comic anthropology: Who were these strange Americans failing to fall in line behind Hillary after eight years of Obama? The Clinton campaign itself didn’t yield any literary journalism of distinction because her road show was a familiar pageant of baby-boomer self-satisfaction, this time to the tune of Rachel Platten’s “Fight Song” instead of Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop.” The single exception was Eileen Myles’s endorsement of Clinton for BuzzFeed: “I don’t think Hillary has horns though she does have a vagina and wouldn’t you want it sitting on the chair in the Oval Office (not to get all weird) because things will never be the same.” It’s no accident that these essays tend to tell us more about their authors and the crowds they mingle with than the politicians who are their ostensible subjects: We already know too much about the politicians.

On the campaign trail with Fountain, you don’t feel, as you do with Saunders, that you’ve been delivered to a parallel America, one even more paranoid and violent than the one you know from television, or, as with David Foster Wallace on the bus with John McCain in 2000, to a David Lynch movie version of politics. Going on the road tends to send Fountain’s mind spinning back into the past. The title of his book follows from the idea that since the Revolution, the United States has experienced a crisis and a reinvention every eighty years or so. He returns often to the Civil War and the New Deal to glean lessons for the present crisis. Fountain’s idea happens to be a saner version of the generational theory put forward by William Strauss and Neil Howe in The Fourth Turning, one of Steve Bannon’s favorite texts. The question, however, is whether we really are undergoing a revolution on the scale of the Civil War or the Depression and its aftermath. As Fountain writes, the late 1960s were a more violent phase in our history than anything we’ve seen recently. And the civil rights movement and the Reagan administration were both more politically transformative than the Trump administration has been so far. As Reihan Salam has argued, beyond the president’s trollish antics, his administration’s policies—even on Russia and immigration—have mostly offered continuity with those of the Obama and Bush administrations. But when Trump does anything, he does it to maximize the divisive noise. And we have the volume turned all the way up.

What’s been bizarre and frightening from the start has been how many have reveled at the spectacle of his politics of negation. At a Trump rally in a middle-school gymnasium in Clinton, Iowa, Fountain notices something that mostly got lost in the picture of the punchy Trumpist who has dominated our memory of the campaign: It was fun for them. “People are happy, there’s much milling and moving about, a church-assembly sort of cheer in the air.” They enjoy Trump’s signature pre-speech playlist of classic rock, Adele, and Pavarotti. But they are also racist conspiracy theorists with a taste for bogus viral images. Over the shoulders of a pair of middle-aged couples, Fountain spots a phone being passed around with a photo of Barack Obama kissing a man as Michelle Obama and Oprah Winfrey look on aghast.

Wife: “Is that real? That can’t be real.”

Husband: “It is, [so-and-so] sent it to me this morning!”

The wife studies the photo. “He is so gross,” she says, and hands the phone back to her husband, though whether it’s Obama who’s gross or the friend who sent the photo is unclear. Next to me a reporter from the Guardian is interviewing another foursome, everyone strong for Trump. Why?

“He’ll take care of the rabies.”

Rabies?

There are smiles, sideways chuckles.

“The Arabs.”

I expected to have to work somewhat harder to find the cliché Trump supporter.

These are the twin notes of Fountain’s book: an openhearted patriotic spirit of fellowship with his countrymen and a mounting sense of distress that Americans have always been but are now especially vulnerable to fraudulent appeals to their ugliest instincts. Most of his excursions on the road and through the past yield a tableau mixing the venal and the humane. But understanding requires an index of national villains. An essay on “The Phony in American Politics,” pegged to the month of February, when it became clear that Trump wouldn’t fade away in the manner of a Michele Bachmann or a Herman Cain, recounts the careers of Texas governor and US senator Wilbert Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, a Depression-era huckster of Hillbilly Flour who used radio broadcasts the way Trump uses Twitter, and Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy, an obvious precedent for Trump not least because his partner in red-baiting was Trump’s mentor Roy Cohn. Sketching the history of racial politics since World War II and the GOP’s Southern Strategy, Fountain paints Trump as the second coming of Barry Goldwater. The cynicism of the electoral tactics has lasted five decades; Trump’s innovation was to abandon the dog whistle for the bigoted bark.

What galls Fountain most about Trump is his chicken hawk posturing. The draft dodger’s bellicose rhetoric goes hand in hand with a general suppression of the realities of American military violence, the sufferings of veterans and the carnage inflicted abroad, especially on innocent civilians. Fountain points to the writings of Ambrose Bierce, who took a bullet to the skull in the Civil War. He also visits an NRA rally in Kentucky and notices that much of the advertising for the hardware being peddled touts its effectiveness at cutting through human flesh and bone. He’s not entirely anti-gun and cites, oddly though not unreasonably, Hunter S. Thompson as an example of responsible gun ownership, and he’s gladdened wandering away from the convention to Louisville’s Festival of Faiths, where he attends a panel on Islamophobia. “America is various. It refuses to be all one thing or all the other,” he assures us, and then visits the childhood home of Muhammad Ali, whose conscientious objection to the Vietnam War he cites as an example of true freedom.

But there are only so many lessons from history you can toss in the face of Trumpism. None of them stick. The strongest and most damning section of Beautiful Country Burn Again is the part that’s been most heavily revised in the election’s aftermath: a history of Hillary Clinton’s career, the New Democrats (used interchangeably with the term “neoliberal” in its less systemic sense), and Third Way-ism tied to an account of the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. Fountain’s account is familiar, drawing on the work of Joan Didion, Thomas Frank, and Matt Stoller, among others, and generally congruent with the case Sanders made against Clinton in the primaries. The Democratic candidate emerges as one of the architects of a system that has yielded derelict factories, stagnating wages, widening income inequality, and impunity for the bankers who brought about the financial collapse of 2008 and its real and widespread material suffering. Fountain is sharp on Clinton’s inept handling of her speeches to Wall Street, painting her as the tool of “a morally bankrupt system that she’d played a large and active role in creating”: “This was the world she lived in, this system; to the extent that she was capable of seeing herself as a creature of the system, we can assume that she viewed it as benign rather than bankrupt, a force for the general good.” Those who didn’t see it that way decided to “opt out and join America’s largest political party,” i.e. nonvoters, or cast their vote for a “perfect horror show”: “Nihilism’s a blast for people who’ve been lied to all their lives.”

That the choice came down to Clinton or Trump was television’s revenge on American politics, abetted by its warped sibling, social media. It was, in the end, a contest of celebrities, and Trump with his trickster tactics of humiliation and shameless self-contradiction—compounding his decades in the tabloid spotlight, his years posing as a corporate demigod on reality TV, and the ready-made propaganda of Fox News—was an effective enough celebrity to tip the electoral college, and certain regional ratings, his way. One thing about celebrities is that the public grows tired of them, as polls leading up to the midterms seem to indicate is happening with Trump. Our best hope for 2020 is that a superior celebrity emerges and everybody changes the channel.

Christian Lorentzen writes the books column at New York magazine.