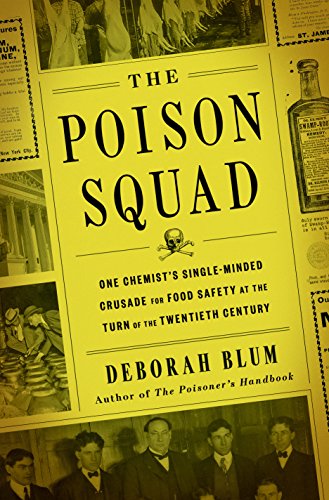

“The devil has got hold of the food supply in this country.” This was the conclusion of Nebraska Senator Algernon Paddock, chairman of the Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, in 1891. That year, he sponsored a bill that would become just one more failed legislative attempt to require food producers to label their products truthfully. Among the transgressions he was trying to stop were common practices like whitening milk with chalk, “embalming” corned beef with formaldehyde, lacing fake whiskey with soap (it made the liquid bead on the glass), and creating ground “pepper” made of “common floor sweepings.” It was not until 1906, after nearly two decades of testing, research, and political combat, that the country’s first Pure Food and Drug Act was signed into law, by President Theodore Roosevelt. As Deborah Blum writes in The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, if not for the perseverance of Harvey Wiley, a government chemist who’d grown up on an Indiana farm that served as a stop on the Underground Railroad, it never would have happened.

Wiley started his career testing food and drink for foreign substances, which almost invariably turned up staggering results. In 1892, for example, he reported that “87 percent of all ground coffee samples tested were adulterated [and] ‘one sample contained no coffee at all.’ ” From there, he moved on to form the “squad” of the book’s title, a team that undertook a series of human experiments at the agriculture department’s Bureau of Chemistry starting in 1902. They began by testing the health effects of chemicals being added in unregulated quantities to American food, as companies such as Pfizer and Monsanto (still with us today and still creating public-health crises) rushed to capitalize on new preservatives and additives with names such as Freezine, Preservaline, and—I can’t help reading this one as an homage to cabaret—Rosaline Berliner. Producers themselves, eager to turn a profit regardless of safety, were incredibly lax when it came to additives: “One standard approach involved making a solution of residues from food and drink products and injecting that solution into rabbits. If the rabbits didn’t die within minutes, food manufacturers would declare the material to be nonpoisonous and safe for human beings.” In the face of this rampant hazard, Wiley held fast to his belief that “if Americans consumed multiple doses of untested compounds in every meal with no assurance of their safety . . . then government officials like himself were failing them.”

It turned out that Wiley’s suspicions about the dangers of ingesting the likes of borax and salicylic acid were correct, but it took another four years for his findings to force government regulation. During that time, the publication of Upton Sinclair’s meatpacking exposé, The Jungle, provided much-needed support, as did legions of women activists, of whom a prominent male food-magazine editor wrote, “Now let the food adulterer quail, for we have the women on our side.” The Pure Food and Drug Act went into effect in 1907, but by the end of that same year, the secretary of agriculture, who had initially gone along with Wiley’s efforts, informed him that the department “was, in fact, dedicated to the support of agribusiness. From now on, he expected Wiley to do a better job of remembering that.”

This, of course, is a very familiar portrait of American business. I didn’t expect to be continuously reminded of our current political regime while reading a book about the early-twentieth-century origins of food safety, but in retrospect, the connections seem obvious. Business interests have long been the engine of government, in spite of the values of people like Wiley. In his day, as now, reporters investigated claims of wrongdoing and exposed the underbelly of the industry, endeavoring to tip the scales in favor of the protection of citizens. And now, as then, watchdog groups are sounding the alarm. We experience—often multiple times a day—a similar dispiriting sense of unreality and powerlessness. Lincoln Steffens, a journalist at the famous muckraking magazine McClure’s, once described this dynamic to Sinclair. In the opinion of Sinclair’s editor, some of the passages in The Jungle were so far beyond the pale they created a book of “gloom and horror unrelieved,” and should be cut. Steffens advised Sinclair to keep every word, but not to overestimate the power of those words to change anything. Sometimes, he said, “it is useless to tell things that are incredible, even though they may be true.”

Blum takes up these parallels in her epilogue, in which she addresses the orange-haired elephant in the room. Citing Donald Trump’s campaign promise to “submit a list of every wasteful and unnecessary regulation which kills jobs, and which does not improve public safety, and eliminate them,” she notes that the current Food and Drug Administration commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, “followed that promise by saying that while he recognizes the importance of food safety legislation he wants to ‘strike the right balance.’ ” As the old saying goes, one man’s idea of waste is another’s gift to lobbyists. Most recently, the FDA has moved to restrict the use of the word milk in describing plant-based products such as soy milk and almond milk, because, as Gottlieb put it, an “almond doesn’t lactate.” It’s no coincidence that dairy companies have been pushing for the change, or that nondairy-milk sales have increased by 61 percent in the past few years while dairy-milk sales have fallen.

This may very well be the moment at which our trajectory permanently diverges from Wiley’s. He at least got some protective laws through, while we’re headed in the other direction at the highest levels of government. Finding the way back will be as tricky as finding the house dust in ground pepper.

Melanie Rehak is the author of Eating for Beginners (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).