EARLY ONE morning in February 2012, as the Syrian army was pounding the besieged city of Homs into submission, artillery fire crashed around a building in the embattled district of Baba Amr. As rocket fire closed in, the handful of foreign journalists and activists who’d been using the building as a makeshift media center panicked.

Marie Colvin, the American correspondent for England’s Sunday Times newspaper, dashed into the street seeking escape. Outside she was struck by a rocket and died instantly. French photographer Rémi Ochlik, running at her side, was also killed.

The journalists’ deaths were no accident, according to In Extremis, Lindsey Hilsum’s new biography of Colvin. Hilsum’s reporting concludes that the Syrian regime set out deliberately to attack the foreign journalists, and Colvin in particular. Colvin had appeared on CNN to decry the slaughter of civilians in Homs; that evening, an anonymous informant tipped officials to the location of the provisional media headquarters. Colvin’s family is also convinced: Her younger sister has filed a lawsuit in a US court, calling the artillery barrage an extrajudicial killing and demanding compensation from the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

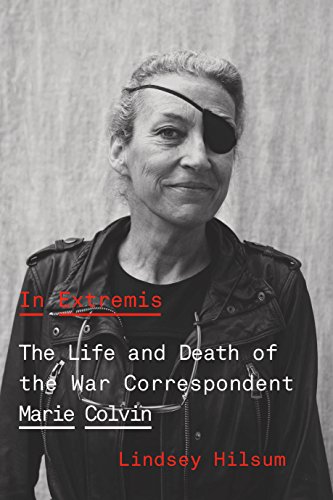

Fifty-six when she died, Colvin had long been a legend among the press corps. Decades of high-risk dispatches layered with keenly observed detail placed her among her generation’s most respected chroniclers of conflict; her larger-than-life personality and iconic eye patch rendered her a character you recognized easily across a briefing room or hotel lobby, but might hesitate to approach.

“Marie Colvin,” sighed a colleague and contemporary when I told her I was writing this review. “She intimidated the crap out of me.” I could only laugh, because I felt exactly the same.

This extraordinarily intimate biography, which draws on hundreds of Colvin’s journals as well as candid interviews with family, friends, and lovers, paints her death as the culmination of a disintegration long underway. Hilsum evokes a martyr in slow motion, battered in body and mind by war even as her scoops and awards and admirers piled up. People were trying to make movies about her life when it should, by rights, have been only half-lived. Conflict reporting had studded her flesh with shrapnel and cost her the vision in one eye. Meanwhile she burned through marriages and love affairs, got hospitalized for post-traumatic stress disorder, and developed an unwholesome relationship with alcohol.

“Panic attacks would hit her when least expected, and she felt a growing sense of unreality,” Hilsum writes, describing one of Colvin’s psychological low points. “Marie was like a wounded animal who had gone to ground, to a dark hole where even her closest friends couldn’t reach her.”

But Colvin kept going back. Describing her life’s work, she mixed unflagging American idealism with gut-deep pragmatism. “Anyway,” she told Hilsum just before her death, dismissing concerns over the high risk of sneaking into Homs, “it’s what we do.”

YOU’RE NOT a war reporter. That’s the first rule of war journalism, one of the fundamental things we internalize as we cover conflict. Let other people say it, but you never describe yourself that way. You have been in dangerous places, taken certain risks, but those brushes with war don’t define you. You’re a reporter. You have other areas of expertise. You’re not an adrenaline junkie chasing bang-bang thoughtlessly from place to place, writing the same old stories about blood and bullets and bombs without regard to the surrounding culture and history.

Anyway, no matter how many wars you document, there will always be somebody else who has done more—a lot of somebody elses, especially in this post-9/11 world where new wars spin off from old ones in a perverse global breeding ground of destabilization.

I’ve seen interviews in which Colvin corrects people who call her a war journalist, but, by any measure, she spent a huge amount of time in combat. She was writing about conflict when I was ten years old and was still at it when I had gone away to write books and have babies. Her life story unrolls against a backdrop of technological innovation and the increasingly ruthless disregard of despotic strongmen for international law, human rights, and the lives of journalists. These two trends would gradually rewrite the ground rules of war reporting—and swallow Colvin whole.

Born in 1956, she spent a restless adolescence staving off the discontents of suburban Long Island with sailing, recreational drug use, and activism. Her wanderlust was awakened by a cultural exchange in South America; her sense of purpose was intensified by watching her father die of cancer. Colvin was a young woman driven by insatiable cravings to travel, to see, to experience. By Hilsum’s account, Colvin showed up in person at the Yale admissions office and—despite having missed the application deadline—managed to finagle a spot. She was brilliant and so, because she tried, she rose. A few years after college, she landed at United Press International, which soon sent her to Paris. She was hired by the Sunday Times and given the plum Middle East beat. The civil war was raging in Lebanon, and there she was. She fell in love with men. She fell in love with Iraq. She floundered, sometimes, drinking heavily and drifting on a vague nihilism.

“The less it seems possible to capture in words anything that makes any sense, the more I want to just quit and live out whatever it is that attracts me, obsesses me, makes everything I left behind which seemed so important fade,” she writes in her journal during her early years, lying in bed in Baghdad. “Not even desire to escape what I left behind, just to shed it.”

It’s difficult to say what makes some writers gravitate to war. We are curious; we seek experience; we flatter ourselves. War makes us feel like we’re covering something that truly and eternally matters, that our work is indispensable. And—we are lying if we don’t admit this—there is something wild and cool; an untethering from drudgery and petty responsibility. Covering war feeds our egos. So we go.

After a long stint or two in a war zone, it gets more complicated. Then you start to struggle with guilt and addiction and damage. It is often easy to go to war, but excruciating to leave. Resuming normal life is exhausting and disorienting. “Being out there, that was what made her feel real,” Hilsum writes of Colvin, “the only thing that countered the sense of insubstantiality that sometimes washed over her, and her fear that one day she would wake up again and not be able to do her job.” Most people do not freeze up or collapse in a war zone; they freeze up and collapse when they are expected to return to their former lives and function as if nothing had happened. To stay out in the normal world you have to figure out what to do about the trauma of your experience, which seldom seems horrible enough to justify a fuss. And, too, you have to stomach the guilt of leaving. People you know start to die. Your colleagues die, acquaintances and friends, and so do people you interviewed or wrote about. Year after year, country by country, the people you knew die violent deaths.

Maybe the guilt never goes away. Even reading in Hilsum’s book about the shelling of Homs, I was washed in guilt. I knew Syria; I loved Syria; I covered Syria for years. I haven’t set foot in Syria since the war started. I sit safely elsewhere while Syrian civilians are slaughtered and their cities laid waste. What was the point of me, what good had I been? It spins into existential places and dark thoughts.

Those are the questions—a cocktail of self-involvement and self-sacrifice—that propel us back into the fighting. The worse you feel, the more likely you are to make a mess of your normal life. The more your normal life is a mess, the more tempting it becomes to go back and lose yourself someplace it makes sense to feel awful. Nobility and ego; convenience and pleasure. Around and around, ad infinitum. One war ends and another begins.

“Have forgotten what it is to go to bed and sleep,” Colvin wrote in 1998. “If I go to bed before 3, lie awake for hours, mind spinning. Drink helps, fall asleep, but morning is lost.”

COLVIN GOT HER START before the relentless efficiency of internet and satellite technology made it impossible to hide from anybody. In her early days, she could fly under the radar of bosses and sources alike. Her stories ran exclusively in print; the people she interviewed were unlikely to see what she’d written about them. She passed through Lebanon, Kosovo, Chechnya, Afghanistan. By the time anybody figured out she was a nuisance, if in fact they ever did, she was usually long gone.

Colvin was old school, undeniably. She scorned feminism and chain-smoked and got away with comparing marauding militias in East Timor to “barbarians” in her copy. She was a paper-and-ink street reporter, and in a sense she was killed by the changes that took place around her as she plugged away with her notebook. But she also pushed the standards of journalistic practice forward. She adapted early to a personalized approach that would later become a sought-after journalistic style. At the urging of her employers, she wrote her stories in the first person. This flew in the face of the long-standing tradition that discouraged news reporters from inserting themselves into the story and favored instead a facade of stoicism and exaggerated self-effacement at all costs—even if the result was a duller story. Colvin also had no qualms about breaking down artificial barriers between herself and her subjects; about sharing their living arrangements and deprivations; about writing herself into the stories. She wanted to go where there weren’t any other reporters and write from ground level—table by table, room by room, street by street. She earned a reputation for going in farther than anybody else and embedding herself in a situation while disaster loomed.

And in this practice, she had moments of glory. During the violence that flared in East Timor in 1999, when virtually every other reporter had fled, she refused to abandon desperate Timorese civilians who’d taken refuge in a UN post. Colvin believed—probably correctly—that once the last foreigner left, the Indonesian-backed militias massed outside the compound would overrun the walls and murder everyone inside. In staying, she took the considerable risk of either starving to death with the refugees or getting slain with them. She called her sister in America to say goodbye and warn her family that she was likely to be killed.

“I just didn’t feel I could live with myself if I left,” she said later. “It was morally wrong, the idea that we would walk out, say good-bye, and all those people knew they were going to be killed.”

Instead, she looted other foreigners’ left-behind luggage for clean clothes and energy bars and sent dire reports that helped shame the international community into arranging an evacuation. Colvin is credited with helping to save the lives of the civilians she wouldn’t leave.

“I embarrassed the decision-makers and that felt good,” she wrote later.

Colvin became truly famous later that year, Hilsum writes, when she nearly died hiking over the mountains into Georgia to escape Russian bombardment in Chechnya. In a way, her reputation was becoming, in itself, a risky proposition.

Colvin was “vulnerable indeed,” Hilsum writes. “Not just because such reporting put her in danger, but because she and her editors let it define her.”

But these were the kinds of scenes and characters she sought. The big picture, Hilsum writes, was less important to Colvin than the universal truth of human experience: “Context mattered, but the experience of individuals in war, whether fighters or victims, was the essence of the story.”

Nor did she pretend to view things objectively when she felt one side was clearly wrong.

“To me there is a right and a wrong, a morality,” Colvin once told an Australian reporter. “And if I don’t report that, I don’t see the reason for being there.”

Colvin was in Sri Lanka in 2001 when she was struck in the face by shrapnel and blinded in one eye. She was crawling with the Tamil Tigers across a darkened field when the Sri Lankan army detected the rebels and opened fire. This injury caused Colvin to wear an eye patch for the rest of her life and entangled her reputation with the cause of the controversial Tigers. Some critics called her a “stooge” for the Tigers; others praised the sacrifice she’d made in service of the story.

That sacrifice, Hilsum writes, “made no difference.” Eight years later, as the Tigers were being crushed in a campaign that reportedly didn’t pretend to distinguish between civilians and fighters, Colvin—who was in London taking desperate satellite phone calls from people trapped in the shrinking scrap of Tamil turf as it was shelled by oncoming Sri Lankan soldiers—tried to persuade the United Nations to oversee the surrender. She was shrugged off, and the surrendering Tigers, along with untold numbers of civilians, are believed to have been slaughtered.

For governments that would rather quell uprisings ruthlessly—and without the annoyances of international law and outside observers—the Sri Lankan counterinsurgency strategy offered an object lesson; as Hilsum writes, it would be “studied in war colleges and defense ministries across the world. . . . The military must be allowed to do whatever it wants, with no regard for civilian life or international law, in utter secrecy, and in defiance of international opinion. The victorious government can then impose a political solution.”

In other words, the conflict in which Colvin lost her eye would show the world how to undo every ethical and moral value she’d upheld as a war correspondent. The Sri Lankan conflict was modern, too, because crucial pieces of journalism—the most haunting and irrefutable documents of the war’s horrors—were not written by ground witnesses like Colvin, but pieced together by deft and distant internet users who uncovered the trophy videos of Sri Lankan soldiers raping and torturing Tamil civilians.

Colvin lost her eye and risked her reputation, but in the end—this brutal thought, again—it didn’t matter. And by the time she got to Syria, the same forces were in play.

Since the earliest days of the uprising, journalists have been risking their skin to get close enough to tell the story of the Syrian war. But a huge proportion of the coverage has been patched together from afar, with a heavy use of videos, internet posts, and other forms of documentation from people whose affiliations and reliability have sometimes become the subject of debate. The collective result has been a disjointed and confusing narrative of a disjointed and confusing war. Somewhere along the way—as Donald Trump declared journalists “enemies of the people”—reporters have become fair game for any despot who dislikes the stories. Some hundred and fifty journalists have died trying to cover the war in Syria, which has been prosecuted in relative obscurity.

Assad wanted no witnesses, no meddlers, no journalists getting in his way. By and large, this ambition has been realized.

They saw Colvin on television. They traced her satellite phone, according to court documents. They took the informant’s tip. It wasn’t hard. She was not difficult, in the end, to kill. Anyway, she was not the first. Anyway, she was warned. Anyway, we are the ones left to figure out our next move.

Megan K. Stack’s Women’s Work will be published this spring by Doubleday.