Late in his memoir, Casey Gerald watches a video of George W. Bush fumbling his way through a story about meeting an underprivileged black youth from South Dallas. The former president’s tale is a version of a familiar narrative, one that Americans trot out as evidence of our society’s fundamentally meritocratic structure: Despite a dead father and an imprisoned mother, despite growing up in the inner-city neighborhood of South Oak Cliff—“you know, on the other side of the Trinity River,” Bush informs us, assuming, correctly, that we all understand the black urban abjection that stems from being on the other side of any river or freeway or train track—the boy he met persevered. Thanks to a dedicated aunt and a successful football career, the black boy eventually made his way to Yale, then to Harvard Business School, then to an encounter with the president of the United States.

Gerald finds the boy’s story admirable—until it dawns on him that he is the black youth Bush is talking about. Bush has drawn on what Gerald told him two years earlier, when they improbably met in a buffet line in Dallas, and while the tale is true in essence, Bush has altered the details. Yes, Gerald, a Yale graduate and cofounder of the nonprofit MBAs Across America, had grown up in poverty and succeeded against the odds. Yes, his father was drug-addicted, emotionally distant, and often absent. But his father’s death was of the social rather than the physical variety, his heroin problem eventually landing him in prison. Gerald’s mother was mentally ill and frequently institutionalized, but she didn’t spend a significant amount of time in prison. And it was his grandmother, not an aunt, who helped raise him and his sister Tashia during one of his mother’s prolonged disappearances. Bush has pilfered Gerald’s story, turning the younger man into evidence of an enduring American fiction.

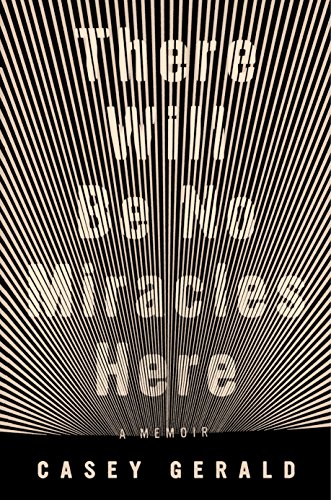

Such tellings, retellings, and emendations haunt There Will Be No Miracles Here, Gerald’s account of his rise from inner-city Dallas to the Ivy League–educated American elite. At its best, the book asks readers to consider how and why black people are called on to tell the nation our stories, what kinds of stories we are commanded to tell, and why society is so eager to wrest them from us when we will not tell them to the nation’s liking. No Miracles dramatizes the incessant circulation of black personal narratives, laying bare their integral relationship to America’s self-conception. Gerald recites the story of his rise to Yale and Harvard in an attempt to shatter the meritocratic fiction that story makes possible, using the memoir form as an aesthetic space in which blackness can erupt in all its complexity.

The version of Gerald’s story that attracted Bush’s attention is one of America’s foundational myths: that individual effort can transcend structural inequality; that, as he says, “if you work hard and play by the rules you can do anything, be anybody, in this country.” It’s the kind of bootstrapping tale that Americans white and black love to hear, and one that sits within a long tradition of black autobiography going back to Booker T. Washington’s 1901 Up from Slavery. That book, which described Washington’s childhood enslavement, the hard work he undertook to educate himself, and his strenuous efforts to teach former slaves the value of self-reliance, helped cement his position as the most powerful black leader of the early twentieth century by conveying an image of his singular industriousness. But that singularity was precisely the problem: By propagating a standard that few black people could actually meet, Washington’s story promoted a mythic path to advancement that masked what his contemporary W. E. B. Du Bois witheringly called a “silent submission to civic inferiority.”

No Miracles is not an updated version of Up from Slavery, or Ben Carson’s Gifted Hands, to name a particularly egregious addition to the canon of black exceptionalism. Rather, the book explores how such stories of singular achievement continue to dominate and manipulate our contemporary moment, and how they determine Gerald’s own life. As a child, struggling to cope with his parents’ afflictions, he develops a foolproof protection strategy. “I had learned that the authorities loved nothing more than obedience, submission . . . or at least if I submitted they would not bother me too much.” Survival depends on his ability to go mentally and emotionally slack, to avoid struggling against the myriad injustices the world visits on him. “It was simple, really: identify who was in charge, find out what they want, give it to them immediately.” This tactic serves him well: Soon, recruiters from Yale arrive at South Oak Cliff High, the oddity of their presence underscored by the metal detectors they must pass through to enter the school. In his college applications, Gerald learns to track his progress through the eyes of others, creating a “thousand-word pastiche of trauma pornography” that echoes the language of Washington’s autobiography. Meritocratic success is a version of his childhood survival strategy: The assignment is to peddle his singular excellence, and he becomes a master of the form.

South Oak Cliff’s hopes hinge on the idea that he has transcended his circumstances. Despite feeling out of place during a visit to New Haven, Gerald decides to enroll anyway, for reasons that have less to do with himself than with an image of himself. At signing day, when he accepts his Yale offer, he looks out over his cheering community and finds himself carried away by “the gust of my people.” Later, weeping with pride, a black groundskeeper congratulates Gerald on his success. The older man can’t find the words to express himself, but his silence speaks nonetheless: “Go all the way,” Gerald hears. His choice to attend Yale emerges from those tears and cheers, from “simply tracing those men’s hands and those women’s voices and those little children’s eyes, even if they pointed to a place at the eastern end of the world that I was too dim to have great passion for.”

The myth of Gerald’s success is crucial to people outside his community as well. His exploits on the gridiron and decision to attend Yale draw attention from local newspapers from Dallas to New Haven. The Dallas Morning News publishes an article extolling his refusal to “let his circumstances define who he is.” Meanwhile, wealthy old white men marvel at his resilience. When Gerald interns at a law firm the summer before heading to Yale, the partners treat him to meals at restaurants where, in his youth, Gerald could scarcely have imagined eating; the only price is that he must recite his story to them. “But if I took too long to tell it,” Gerald remembers, “my host would relieve me of the duty . . . and do it himself.”

After graduating from Yale, traveling through Europe, and working in Washington, DC, he finds himself back in Dallas, planning to put together a bid for Congress, like many a dutiful Ivy League graduate with a political-science degree. Having run himself through the machine of American elite society, however, Gerald is alienated from the friends, family, and black social life that had once defined his existence. His time at Yale taught him to be ruthless, to train his eye on his goals and disregard anything else. As a result, he is hollowed out, emotionally exhausted and reduced to a symbol. And being a symbol, as he says, “is truly the world’s loneliest job.” In heeding his community’s desire that he traverse the Trinity River to join the meritocratic elite, he has deracinated himself. He will forever be caught between two worlds: “You can never fully be a part of this new world,” he writes, “but you can’t go back to the old world, to your people, because you are now, for them, a symbol of what they can be.”

Rejecting life among this elite—“I had strived to win this world,” he writes, “and won my death instead”—Gerald has responded with a compulsively exuberant memoir steeped in the black vernacular. In No Miracles, he doesn’t want to transcend his circumstances. Instead, he basks in the memory of them, unfolding those layers of his story for which the autobiography of excellence can make no place. Often, the book reads like an attempt to reconstitute the community, and communicate the experience, that the narrative of singularity would pluck him out of. So we get gorgeous evocations of Gerald as a queer black boy trying to navigate a world in which evidence of his sexuality is met with derision. We get lovingly crafted remembrances of a childhood spent watching his mother put on her makeup. We get moments like his encounter with D’Angelo’s video for “Untitled (How Does It Feel),” where he stares in rapture as the camera pans up and down the singer’s chiseled body. “I watched D’Angelo’s video for this song . . . crouched before the screen in the dark with the sound off, so that everyone in the house thought I was asleep,” Gerald writes. D’Angelo’s question—How does it feel?—seems to get at the heart of this memoir: It doesn’t want to present us with the black boy as an image into which we can pour our desires. It wants to pierce the symbol so as to inquire about the experience of black being—How does it feel to be a problem? as Du Bois asked. How does it feel to be a thorn in the side of American society?

Gerald’s efforts to encompass the totality of his experience sometimes come at the expense of depth. No Miracles skitters from episode to episode, granting equal weight to each, with the result that no one story feels particularly consequential. Worse, he can be maddeningly vague at pivotal moments: We don’t learn the specifics of his encounter with Bush, for instance, and Gerald gives no explanation for how a civilian happened to run into a former president. Ironically, the only story the book renders in intense detail is Gerald’s ascent to the Ivy League. For all of the criticism it aims at the meritocratic elite, this memoir saves some of its lushest and most evocative storytelling for describing that elite’s milieu. In these moments, No Miracles seems most interested in exactly what it claims to refuse: recounting the rise of an exceptional figure. That’s unfortunate, because despite the book’s shortcomings, Gerald is a vivid and compelling narrator. Like Zora Neale Hurston’s, his prose shines with the verve, intelligence, and inventiveness of the black vernacular, and his memoir is a crucial intervention in a literary landscape where black people are often compelled to recite their stories at their own expense.

Ismail Muhammad’s writing has appeared in the Paris Review, The Nation, and other publications.