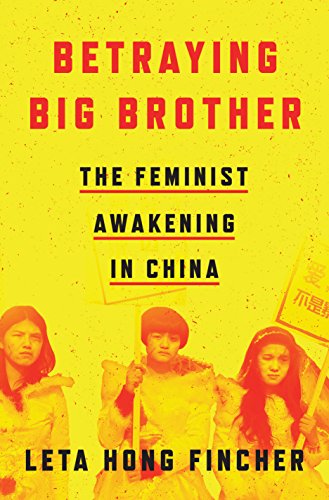

On March 6, 2015, just before International Women’s Day, authorities in cities around China rounded up feminist activists to preempt a planned public demonstration. The women were sent to a detention center in Beijing, where they were held for over a month on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” While in custody, the activists were isolated from friends and family, subjected to constant interrogation, and deprived of medical care. Their offense? A plan to distribute anti-sexual-harassment stickers on public transportation. “Had they not been jailed, their activities likely would not have attracted much attention,” Leta Hong Fincher writes of these women, who became known as the “Feminist Five.” Instead, their detention “sparked the creation of a powerful new symbol of dissent.” In her sprawling and detailed recent book, Betraying Big Brother, Fincher aims to tell the story of the women’s rights movement in China through their saga. Fincher bases her narrative on interviews with the Five and their allies, while supporting their stories with deep research into the roots of the government’s crackdown on feminism. The book also looks ahead, sizing up China’s emerging #MeToo movement.

Wei Tingting, Wang Man, Li Maizi, Zheng Churan, and Wu Rongrong had worked for years on social-justice projects before they were detained. Previous actions like “Occupy Men’s Toilets” (highlighting the shortage of public women’s bathrooms), “Bloody Brides” (a Valentine’s Day street action against domestic violence), and “Bald Sisters” (a demonstration in which women shaved their heads to call attention to discrimination in university admissions) had not resulted in arrest or gotten much of a reaction from the government at all. (The public-bathroom protest even elicited a promise from provincial officials to address the problem.) Fincher explains this seemingly incongruous attitude toward women’s rights as part of a larger pattern. The Chinese government is willing to tentatively support—or at least overlook—women when it’s convenient for the regime, but right now, it’s not.

Fincher traces this dynamic back to the very beginning of the Chinese Communist Party, narrating the story of Wang Huiwu, wife of CCP cofounder Li Da. After the party was established in 1921, Wang organized an independent women’s group, oversaw a Communist-affiliated girls’ school, and published a feminist journal. But when Li lost his Central Committee reelection bid a year later, “other male Party leaders could not accept the idea of a woman holding a more important position than her husband,” Fincher writes. Wang was removed from her leadership role, and the journal and school were both shut down. Later that decade, the party renounced the use of the word feminism entirely, preferring to focus on “the elimination of private ownership and the class system.” Members of the party’s All-China Women’s Federation “had to hide any real efforts to promote a women’s rights agenda.” Betraying Big Brother goes on to detail the larger, self-interested strategy that guided the government’s attitude toward women’s rights in the years that followed. Fincher locates its roots in the Communist Revolution of 1949, when the party pushed women-oriented policies—promoting women’s literacy, abolishing arranged marriages, and instituting the right to divorce—to encourage them to join. At the time, women’s labor was seen as essential to increasing output and hastening the country’s rapid modernization. Women were encouraged to work while also expected to manage childcare and other household duties alone. When job growth stalled in the 1970s, during the opening of the country’s economy, women were fired or forced into early retirement. It became apparent that women had simply been tools to keep the party prosperous and in power.

Most of the Feminist Five, as well as the dozens of other activists Fincher interviewed, expressed an all-pervasive feeling of being both taken for granted and controlled. When the Five were released from detention, the unmarried women were brought home to their parents, despite not having lived with them for years; the police told the married women’s husbands to keep better watch over their wives. While Western readers might be shocked by such outdated, paternalistic attitudes, some of the misogynist regulations detailed here sound very familiar. Strictly controlling reproductive freedom, for example, seems to be a universal approach to keeping women in line. As Fincher writes, “The more women are free agents, independent and beholden to no one, the more they can resist and disrupt the patriarchal authoritarian order.”

Fincher sees signs that this order may be transforming. Lately, “misogynistic, single-shaming, and often homophobic propaganda is increasingly falling on deaf ears,” she writes, “thanks in no small part to young feminists’ influence on social-media discourse.” But, as her history shows, progress is never certain. Right now, China’s censorship of the internet—a problem that Google’s planned collaboration with the government on a state-sanctioned search engine will likely exacerbate—is feminism’s biggest challenge: In March 2018, the popular Weibo account Feminist Voices was permanently banned. Similarly, the #MeTooInChina hashtag has been forced to adapt, morphing into the censor-evading #RiceBunny. Based on Chinese words with a similar pronunciation to “#MeToo,” the hashtag can also be rendered in emoji and has, so far, avoided the blacklist.

Fincher’s obvious admiration for her subjects’ tenacity, strength, and bravery inspires her to believe that it will be impossible to stop the country’s latest feminist wave: “Even if all the feminist activists in China are arrested or otherwise silenced, the forces of resistance they have unleashed will be extremely difficult to stamp out.” That’s a hopeful message, but it’s not entirely convincing. Recent history confirms Fincher’s thesis, both in China and closer to home: Silencing women’s voices just makes the system run more smoothly.

Maggie Foucault is Bookforum’s associate editor.