How good was Lucia Berlin? She published her first story in 1960 at age twenty-four, but her debut volume, Angels Laundromat (1981), wouldn’t appear for another two decades; Phantom Pain followed in 1984, and Safe & Sound in 1988; all three came out with small presses. Her readership grew slightly when Black Sparrow Press took her up, publishing Homesick (1990), So Long (1993), and Where I Live Now (1999), but even their support wasn’t enough; nor was the esteem in which Berlin’s terse and minimal style was held by Lydia Davis, Saul Bellow, and Raymond Carver. By the time A Manual for Cleaning Women appeared, the selection that finally won Berlin a wide audience, it was 2015, and she had been dead for eleven years.

In her foreword to that book, Davis wrote of the “buzz and crackle” of Berlin’s language, of Chekhovian stories in which “the live wires touch”; but she also identified what would, at last, make Berlin’s book a best seller (and within weeks of its release). As if by some retrograde magic, Berlin had tapped an unborn cultural pulse, responding in advance to a millennial demand for writing that troubled—sometimes even dissolved—distinctions between fiction and memoir. “People talk, as though it were a new thing, about the form of fiction known in France as auto-fiction,” Davis wrote, but “Lucia Berlin has been doing this, or a version of this, as far as I can see, from the beginning, back in the 1960s.”

Berlin didn’t have to be a woman to be overlooked, but it probably helped. Her best stories, about single mothers scraping by on the Pacific coast, drew on troubles of her own. She worked as a cleaning woman, a switchboard operator, an ER nurse—anything to support her four sons. Like several of her narrators, she had scoliosis; like one of them, she had been sexually abused by her grandfather while he sang “Old Tin Pan with a Hole in the Bottom.” And, like practically all her characters, she was an alcoholic. Mark, Berlin’s eldest son, described her fiction succinctly: “Not necessarily autobiographical, but close enough for horseshoes.” Her publishers mainly distributed on the West Coast, and that, together with her near-photographic descriptions of life by the Pacific, helped to pigeonhole her as a “regional writer.” Like Eudora Welty, Berlin felt patronized by this designation, which didn’t “differentiate between the localized raw material of life and its outcome as art.”

Whatever else contributed to her critical and commercial neglect, her sentences weren’t the problem. Berlin is forensic in her quality of observation, and her prose rhythm is almost notational in its fluency. Consider these examples: “Women’s voices always rise two octaves when they talk to cleaning women or cats”; or, “I’ve worked in hospitals for years now and if there’s one thing I’ve learned it’s that the sicker the patients are the less noise they make”; or, “The liquor stores are gigantic Target-size nightmares. You could die from DTs just trying to find the Jim Beam aisle.” Each sentence has the ring of an aphorism coolly expressed, but beyond that, teasingly, a tremor of vulnerability. It’s like a hint of something askew in an inner realm.

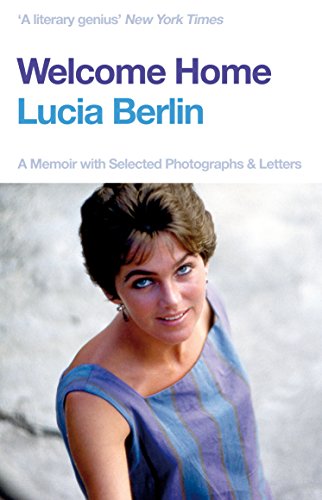

Welcome Home is FSG’s attempt to prevent Berlin once again slipping from public view. The first half of the book is an unfinished memoir, interspersed with photographs; the second is a selection of letters that Berlin wrote to family and friends between 1944 and 1965. The former mimics the nomadism of her early life by proceeding in darting, elliptical installments, each of which is prefaced by a location. There’s Juneau, Alaska, where Berlin was born in 1936; the mining camps of Mullan, Idaho, and Deer Lodge, Montana, where her father eked out a living before he joined the Navy; her grandparents’ house in El Paso, where Berlin and her mother and sister passed their days waiting for him to come home. In Santiago, Chile, she spent a flamboyant adolescence (golf, country clubs, fancy hats); in Albuquerque, she married her first husband, and in New York she lived with her second. The book trails off in Mexico in 1966, two years before Berlin got divorced for the third and final time. Her best stories were yet to be written: “Tiger Bites” (about a back-alley abortion in Juárez), “Unmanageable” (about fighting off delirium tremens while getting the children ready for school), and “Silence” (about living with her “Ku Klux Klan grandpa” in Texas). All were composed in the 1980s and ’90s, after Berlin gave up on her dream of a nuclear family and took to writing about everything that was wrong with her own.

She admired Carver “before he sobered up and sweetened his endings.” “Our ‘styles,’” she said, “came from our (similar in a way) backgrounds. ‘Don’t show your feelings. Don’t cry. Don’t let anyone know you.’” This makes me think of the sign pinned to a noticeboard in her story “Angel’s Laundromat”: NEW CRIB NEVER USED—BABY DIED. Her lines are so clear-eyed, so remorseless; they leave the skin like an alcohol rub.

Occasionally Welcome Home has the succinctness and survivor’s humor that mark Berlin’s stories. (“If I’m feeling sorry for myself,” she told an interviewer in 1996, “I’m not going to write.”) Take the account of her disastrous marriage—the first one—to the sculptor Paul Suttman. “I held the hot part of the cup and gave him the handle”: That’s how she defined their dynamic.

He made me sleep lying face down on the pillow, hoping to correct my “main flaw,” a turned-up nose. Of course there was the big flaw, my scoliosis. The first time he saw my naked back, he said, “Oh God—you are asymmetrical.”

Later, she recounts their breakup:

I accidentally got pregnant again when Mark was only a few months old. Paul said the only solution was for him to leave, so he did. He had a grant, a patron, a villa and foundry in Florence, and a new straight-nosed girlfriend.

She doesn’t ask him to stay. The morning he leaves, she gives away his Java temple birds to an old lady across the street.

In 1961, Berlin moved to Mexico with the jazz musician Buddy Berlin. The most idyllic passages in Welcome Home are drawn from this seven-year marriage. We relax into the house they shared by a coconut grove in Jalisco, with its thatched-palm roof and floor of fine white sand; Berlin’s sons are out in their “racing canoes,” and their laughter is “echoing above the water”; Lucia and Buddy are taking off in a little Beechcraft Bonanza “to watch the sun set over Albuquerque, flying low over the flaming-red foothills, then banking around to follow the spill and tumble of colors all the way into Arizona.” But along it comes, the heroin. “As if addiction had sent out loud heartbeat messages, the drug dealers began to show up.” The better days, filled with “big parties where we ate lobster and clams we had shipped in from Maine,” are slowly replaced by blackened spoons, needle marks, vials of pure morphine. “‘You only look in my eyes now to see if they are pinned,’ he said. True.”

How do you read the memoir of a writer whose fiction comes from life? Because Berlin’s stories have the force and feel of autopsies; because we’re dealing with a writer obsessed with the insides of things, and determined to poke around; because Welcome Home was written in the early 2000s, after Berlin’s most intimate biographical stories had been published, we might expect the memoir to go further than the fiction, to give us something more like a definitive portrait of Lucia Berlin. I’m not sure that it does.

The memoir’s most affecting entry describes her grandparents’ house in El Paso. She sums it up as follows: “Cockroaches, dark hall, three mean drunks. Drought. Flood.” Here’s the smell of “sulfur, wet dirty laundry, cigarettes, whiskey”; here’s her grandfather reading the paper and burning it “page by page in a big red ashtray.” Sharp details, but there’s little in Welcome Home to rival the lurid, often grotesque, precision with which El Paso is rendered in stories like “Silence,” “Dr. H. A. Moynihan,” “Stars and Saints,” or “Mama,” all published decades before. In the memoir, only Berlin’s description of her grandmother’s skin—“white and moist, the exact texture and temperature of Ethiopian bread”—can stand with the best of its sibling fictions.

The El Paso years, as she describes them in Welcome Home, seem sanitized because of what Berlin leaves out. I’m thinking, perhaps inevitably, of her grandfather’s sexual abuse, an omission that’s curious not just because of its lasting effect on her, but also because of the openness with which she wrote about it in her stories. Here’s a passage from “Silence,” first printed in Fourteen Hills journal in 1998 and narrated in the voice of a girl with a brace on her crooked back:

I tried to hide when Grandpa was drunk because he would catch me and rock me. He was doing it once in the big rocker, holding me tight, the chair bouncing off the ground inches from the red hot stove, his thing jabbing jabbing my behind. . . . Only a few feet away Mamie sat, reading the Bible while I screamed, “Mamie! Help me!” Uncle John showed up, drunk and dusty. He grabbed me away from Grandpa, pulled the old man up by his shirt. He said he’d kill him with his bare hands next time.

The simplicity, the understatement, has nothing to do with stoicism; it contributes to the superficial numbness of Berlin’s style, so that the failed rhetorical parallel becomes a flawless emotional one. There’s an extraordinary moment later in the same story where Uncle John learns that Sally, the little sister whom Lucia “envied” with “a violent hissing,” has also been molested. “You think Sally has it pretty good,” he surmises. “You’re jealous of her because Mamie pays her so much attention. So even if this was a bad thing he was doing at least it used to be your bad thing, right?” Sexual abuse, Berlin wants us to see, may have to do with trauma and shame; but it also has plenty to say about sensuality and envy and curiosity.

“I know that it is true that Grandpa shot him,” Berlin writes of Uncle John in “Silence,” “but how it happened has about ten different versions.” Imagine a life story in which each of those versions is given equal play, in which distance, forgetfulness, reflection, and redescription are what give a memoir its shape. This life story might look something like a compendium of Berlin’s fiction: The rough coordinates remain the same (El Paso and Santiago, Mexico and Berkeley), and the characters recur (pervy grandfather, spiteful mother, junkie husband), but the perspective inches and shifts. The story could be narrated by Lucia, or by one of her many aliases: L.B., or Carlotta, or Dolores, or Lucille. “Everything I write is autobiographical,” she said in 1990. “I don’t know why I have my name in some stories and not in others. Come to think of it I don’t know why I don’t have my name in all of them. I can’t imagine what effect this has upon readers . . . I hope they feel that the story is true.” Welcome Home is her attempt to dispense with narrators, to write a straightforward, nonfictional account of Lucia Berlin’s past. The reason it doesn’t come off has to do with the dictates of conventional memoir, with the demand for a single, definitive version of the past. The multiplicity of perspective that Berlin brought to bear on her life in her fiction was a sort of insurance policy. Each verbal snapshot was clearly delineated, but it could only be “true” just there and then, because it was one of several possible executions. To understand what I mean by this, you need to understand how memory works in Berlin’s stories.

In “Stars and Saints,” she gives a typical account of her mother’s vitriol during their bleak El Paso years:

She stood at the top of the stairs with a blue airmail letter from my father in one hand. With the other she lit a kitchen match on her thumbnail and burned the letter as I raced up the stairs. That always scared me. When I was little I didn’t see the match, thought she lit her cigarettes with a flaming thumb.

The collapse into the child’s mind is what makes it. “When I was little I didn’t see the match, thought she lit her cigarettes with a flaming thumb.” In the topography of the sentence, the cruelty of the mother is less something the child recorded and preserved than something the adult has reached back and created out of emotions both fresh and old. Reading through Berlin’s stories, we build up a picture of her mother through an incremental haze. She closes the venetian blinds when Lucia’s sister comes to announce she’s dying of cancer; she slits her wrists and signs the suicide note “Bloody Mary”; she overdoses and writes that she’d “tried a noose but couldn’t get the hang of it.”

Then, just here, just when you think you have the measure of her, along comes a story like “Panteón de Dolores,” in which Berlin speculates what it would have been like for her mother after her grandparents lost their fortune in the Depression.

Everything was grim. And scary probably, if Grandpa did to her what he did to both Sally and me. She never said anything about it, but he must have, since she hated him so much, would never let anybody touch her, not even shake hands . . .

Berlin’s work is about old violences, and their survival in a shape we do not, and often cannot, recognize. We could think of her stories as the unsuccessful attempt to write her memoir, as a Penelopean endeavor in which the tapestry of her life is woven and rewoven. There’s a freedom in that.

Being tied down doesn’t suit Berlin; this is one reason why Welcome Home, a singular account of a kaleidoscopically complex past, doesn’t work as well as the fiction. She was best with wiggle room, with the freedom to use her myriad iterations of the past to constitute the present. In 1960, when Little, Brown offered her an advance for a novel she was already writing, she hated the “mercantile ring” of it all, and was terrified of being forced to complete a narrative in which she might lose belief: “I could have been a writer, but it would have been too hard to care more about what I saw and how I said it, than what I felt, what I was.” Toward the end of Welcome Home, there’s a letter to her friend Helene Dorn in which Berlin recounts meeting her agent Henry Volkening and a representative from Little, Brown over drinks. Berlin becomes irate when Volkening—“a goddamn pimp,” she tells Helene—tries to flog the novel to the publisher while his author is in the bathroom. Informed of this when she returns, Berlin waits until Volkening, eight bourbons down, gets up to follow suit, and as soon as he’s gone, she torpedoes the deal. Afterward, in the lobby, the agent is bullish: “Well, you’ve cinched that, honey.” “The only move short of kicking him into the palm pot,” Berlin tells Helene, “was simply to say to hell with him, which I easily did. . . . And I feel great—maybe I’ll never write another word for the rest of my life, maybe I will. That, too, will never be a task again.” Perhaps Berlin, herself, had a hand in her own obscurity.

Joanne O’Leary is an Irish writer and an editor at the London Review of Books.