ORIGIN STORIES are inescapably political. Battles to crown the “first” abstract artist might be bloodless, but they have been fought fiercely, for decades, by art historians seeking to establish a definitive breakthrough. Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, František Kupka: The story of modern Western nonrepresentational art has typically begun with a few European men jockeying for position as “figure one.” Since the relatively recent awareness of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), who produced innovative and boldly graphic abstract work predating that made by these better-known men, scholars and curators have revised this narrative, bowing now before their queen.

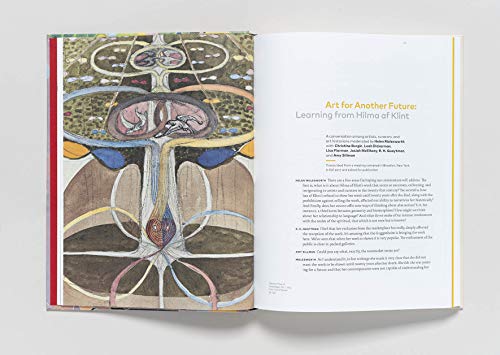

But the recent publication of two books, Hilma af Klint: Notes and Methods and Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, complicates the triumphant fairy tale. The first is a reproduction of af Klint’s early notebooks and presents comprehensive English translations of her enigmatic writings; the second is the exhibition catalogue that accompanies her blockbuster show at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York). Both volumes bring nuance to our understanding of the artist’s biography and her formal achievements. And these achievements were strikingly diverse: She created symmetrical paintings with crisply delineated squares and triangles—studies in the rigors of rectilinear structure—as well as more gestural works with fluid curlicues that swoop and swirl across the surface of her canvases.

Born to a prominent seafaring family (her father was a Swedish naval commander), af Klint was among the initial cohort of female students accepted to the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, where she learned the rules of one-point perspective and showed promise with her naturalistic landscapes, closely observed portraits, and tenderly wrought botanical illustrations. After graduating with honors in 1887, she established a studio in a central cultural district of the bustling capital, selling conventional artworks reminiscent of the ones she made in school. Though these works depict the known world through detailed drawing and painting, she became increasingly fascinated with the unseen forces that govern the universe, having attended her first séance at age seventeen. She became more deeply involved in mediumistic quests after the death of her younger sister, and in 1896 af Klint and four other women, calling themselves The Five (De Fem), began to meet regularly to delve into serious spiritual investigations. She was also influenced by contemporary scientific advances that emphasized the materiality of phenomena that cannot be detected by normal human senses, such as the proof of transmission of electromagnetic waves in 1886 and the discovery of X-rays in 1895. These fascinations did not make af Klint an isolated outlier: Probing the porous boundary between dead and undead, and mingling science and the supernatural, were in keeping with larger movements blossoming at the time. She joined the Theosophical Society in 1889, its inaugural year in Sweden, and later became a dedicated acolyte of Rudolf Steiner’s splinter group, the Anthroposophical Society, which held that spiritual transcendence was possible through the objective cultivation of intuition and “supersensory consciousness.”

Over the course of a decade, The Five developed a collective practice that laid the groundwork for some of af Klint’s pioneering visual feats. After praying and reading passages from the Bible, The Five generated drawings in trancelike sessions, transcribing messages they received from astral beings that they referred to as the High Masters. Notes and Methods reproduces pages from one of The Five’s 1904 sketchbooks, which were kept by af Klint until the end of her life; these automatic drawings—some of them signed by the entire group—are dynamic and strange. Biomorphic petals and spirals radiate across the page; densely scrawled circles pulse with energy; shaky dotted lines seem to plot imaginary maps or trace the veins of leaves from unknown trees.

Tucked inside this sketchbook was a handwritten letter, dated 1903, that appears to be addressed to The Five from the “invisible powers” that guided their hands: “How often have we heard you say that everything is futile, that nothing comes of all your labors. Yet like amorphous buds your endeavors sprout in all directions. You see everything as formless and you forget that this is a sign of life.” These encouraging words would soon ring with special urgency, when during a séance conducted on January 1, 1906, an otherworldly guide The Five called High Master Amaliel commissioned a series of paintings that would depict “the immortal aspects of man.” Af Klint accepted this ambitious task, one so absorbing and momentous that she thought it would take at least a year to realize. The other women in The Five feared the project might bring her to the brink of madness; instead, it catalyzed her most decisive artistic advances.

Beginning in November 1906, after spending months in a preparatory purification period, af Klint fervently pursued this divine directive. She labored in spurts for nearly ten years (pausing her activity between 1908 and 1912, when she was dedicated to caring for her blind mother), completing the 193 works that constitute “The Paintings for the Temple” in 1915. The earliest canvases in this series integrate recognizable elements like snail shells alongside cursive letters and freely sketched shapes, while later paintings exactingly employ metal leaf to evoke an ascension to heavenly altarpieces and golden planets. In form as well as method, “The Paintings for the Temple”represent a shift away from existing models of artmaking—at least some of them were painted on the floor rather than on an easel. Af Klint assiduously catalogued her process in ten blue notebooks, faithfully reproduced in their entirety in Notes and Methods along with a glossary of her esoteric vocabulary and an index of symbols. She gave somewhat contradictory accounts of how these works were executed, oscillating between claiming an active role in their creation and relinquishing that agency altogether. “It was not the case that I was to blindly obey the High Lords of the Mysteries but that I was to imagine that they were always standing by my side,” she stated. Yet af Klint also said that “the pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings and with great force.”

Taken together, the notebooks and paintings are evidence of a prodigiously curious mind, one riveted by the mathematical precision of geometry and also stirred by earthly and unearthly creatures—a crystalline prism fills a 1915 canvas, while another from the same sequence features mirrored black and white swans, wings spread and beaks touching in a fantastical kiss. Elsewhere, caped men wielding swords make a disjunctive appearance. Though many of her images appear purged of references to the physical world, af Klint was never invested in upholding the false binary of figuration versus abstraction. In some instances, words are used as compositional elements, but these phrases do little to secure the works’ meaning. Across her paintings she played with cosmic contrasts in scale, as when a small orb is nested within a bigger disk, suggesting both the micro (cells) and the macro (celestial bodies). Her color palette, with its frequent deployment of delicate pinks and oranges balanced against solid blacks, is among the most eccentric and compelling in the annals of modernism.

Af Klint kept working after the completion of her mesmerizing “great commission,” and by every measure her output was daunting: some twenty-six thousand pages of writing and twelve hundred paintings. Fearing that the world was not yet ready, she almost never showed her art, instead preparing her work (including assembling the blue notebooks) for a speculative audience, twenty years in the future, that she anticipated might receive it gratefully. Her hunch that she was ahead of her time was borne out when she had a crushing studio visit with philosopher and esotericist Steiner; unenthusiastic, he expressed skepticism about her reliance on channeling. It was also confirmed after her death, when, on the occasion of af Klint’s inclusion in a major 1986 exhibition on the relationship between spirituality and abstraction, “The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, critic Hilton Kramer sneered that she was not in the “class” of Malevich and Mondrian, “and—dare one say it?—would never have been given this inflated treatment if she had not been a woman.” That Kramer would feel emboldened to telegraph his—dare one say it?—grotesquely sexist judgment indicates how risky af Klint’s work truly was and how much is at stake in asserting her place anywhere in (much less at the very beginning of) an otherwise male-dominated lineage.

And there certainly are gendered, maybe even distinctly feminist, consequences for swapping out Kandinsky for af Klint as abstract art’s ground zero. But what exactly those consequences might be is still up for debate, a debate that continues to unfold among the thoughtful essays collected in the exhibition catalogue. Daniel Birnbaum writes that starting with af Klint would necessitate a totally revised canon that would fundamentally alter modernist art history. But are pronouncements of originality paramount for affirming an artist’s importance? Alternative canons are still canons; the most radical implications of af Klint take us out of the “great minds” formula of canonicity altogether and propose murkier and more interesting histories of co-emergence and collaboration. Such histories acknowledge that distinct economic, national, and religious circumstances have led to similarly abstract-looking, but in fact ideologically discrete, outputs.

Indeed, Leah Dickerman, in her contribution to a lively roundtable convened by Helen Molesworth, observes that it is “misleading to try and choose a first or to say it began here or began here . . . because really you would need to parse: First at what?” Powerfully, the exhibition catalogue itself lets certain clashes within the growing af Klint literature go unresolved. It is clearly a measure of her work’s potency that it has led to so many divergent interpretations, and Dickerman’s expression of exhaustion at the airless exercise of decreeing firstness is needed and refreshing. So is painter Amy Sillman’s championing of af Klint’s “tremendous stubbornness and resistance and negation,” a useful formulation that emphasizes her withdrawal as a “euphoric quality” and reframes the story that she timidly hid her work from the world.

The catalogue’s essays, with their wealth of archival research, provide crucial context for understanding af Klint, filling in what had been a partial picture of her influences and milieu. As Julia Voss points out, the artist inhabited a more far-flung, cosmopolitan network than has been previously emphasized—she embarked on a Grand Tour in Italy and exhibited her art in London in 1928. Though she may have been directed by ethereal beings, she also worked within a specific cultural environment: Andrea Kollnitz situates her in broader Swedish modern art movements; Vivien Greene helpfully charts her connections to a national revival of folk art; and Tessel M. Bauduin explores af Klint’s art in relation to the discourse about atomic energy, Darwin’s theory of evolution, and a range of popular occult practices that were not seen as incompatible with “rational” ideas. If af Klint were alive today, she might feel vindicated: In curator Tracey Bashkoff’s overview, she makes much of the irresistible coincidence that af Klint envisioned her work inhabiting a custom-built spiral-shaped temple—an architectural structure not unlike the Guggenheim, which founding patron Hilla Rebay likewise referred to as a “temple” to abstraction.

Occultism and spirituality emerge in Paintings for the Future as the most contentious issues, not least because they are charged by questions of gender; as David Max Horowitz writes, women have historically been understood as best suited for mediumship because they are seen as passive “empty vessels” that can more readily receive visionary flows. A clarifying text by Briony Fer describes af Klint as a diagrammer, and dismisses the artist-as-conduit framework. Instead, Fer declares that “taking af Klint seriously as an artist, in my view, actually requires us to take some critical distance from the mysticism that might have enabled her to make such innovative work. . . . To focus only on the occult symbolic meanings of her work leads inevitably to an interpretive dead end.” (An even deadlier dead end is the argument that af Klint does not count as an artist at all; this is incisively refuted in an essay published in 2017 by Branden W. Joseph.) Surely we need to keep this entire spectrum of inspiration alive to fully engage with a figure as complex as af Klint, a reckoning that entails accepting the works’ spiritual overtones as well as seeing their stylistic strengths. The roundtable takes up further questions of spirituality, gender, and abstraction, with Molesworth furnishing the essential insight that the artworks might not even be nonrepresentational at all, if af Klint was painting what she saw.

The artist requested that her work not be shown for two decades after her death; it is now owned by the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Molesworth’s assembled group discusses her belated reception and the ramifications of her art not circulating, either in museums or on the market, for so long. Despite this lag, in the past few years, as awareness of her work has grown, af Klint has become a genuine, if modest, crossover sensation, from Swedish design firm Acne Studios creating a fashion line in 2014 that took direct inspiration from her color choices and canvases to French director Olivier Assayas’s 2016 ghost story/consumerist psychological thriller Personal Shopper, in which the character played by Kristen Stewart develops an entrancement with af Klint; this mystic encounter functions as a pivotal plot point. The artist’s own life was certainly cinematic—I would not be surprised if a movie, with its intriguing possibilities for an all-female cast and montaged sequences of her painting on the ground, set anachronistically to the delicious Swedish beats of Robyn or the Knife, were forthcoming. A parallel exhibition at the Guggenheim, of works made in dialogue with af Klint by New York artist R. H. Quaytman, a longtime advocate who has done much to increase af Klint’s art-world visibility, will further cement her status as a relevant touchstone for contemporary viewers.

Why the efflorescence of both art-historical and popular attention right now? Af Klint’s ascendancy feels inevitable: She could be viewed as a heroine for our current moment, an artist who rejected commercial success, resisted the pull of self-publicity, and challenged the myth of individual authorship. She presents an appealing model of opposition for art students confused or repulsed by the rewarding of naked, masculinist strivings for immediate fame. But along with her many negations, af Klint also offers a positive lesson: Recall the reassuring 1903 note about her creative labors not being “futile.” Regardless of whether she was the first abstract artist, she listened primarily to the voices she heard—wherever or whomever they came from—in her pursuit of formal experimentation, and invented something of lasting significance.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is professor of modern and contemporary art at UC Berkeley and, for 2018–19, the Robert Sterling Clark Visiting Professor at Williams College.