“The titles of certain books are like names of cities in which we used to live for a time,” Ortega y Gasset once wrote. “They at once bring back a climate, a peculiar smell of streets, a general type of people and a specific rhythm of life.” Uwe Johnson’s Anniversaries is a book to live in: two volumes and more than 1,700 pages of roomy universe, robustly imagined and richly populated. Its streets are long, and its landmarks are varied. Sometimes the weather’s sultry, and sometimes the pipes clang in the cold. But Johnson’s rhythm is always patient, always mesmerizingly meticulous.

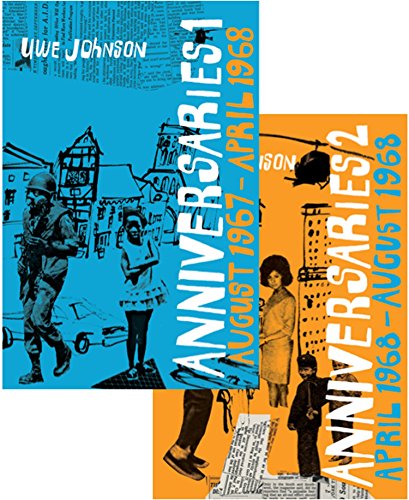

Originally published in four fat installments in 1970, 1971, 1973, and 1983, Anniversaries (in German, Jahrestage, which literally means “days of the year”) follows a year in the life of Gesine Cresspahl, a thirty-four-year-old German émigré living in New York City with her ten-year-old daughter, Marie. Like Johnson, Gesine is a native of the northern German region of Mecklenburg. Like Johnson, she grew up under Nazi and then Soviet rule. And like Johnson, she fled, by way of West Germany, to the clutter and clatter of New York. Johnson lasted two years before he retreated, first back to Germany, then to a remote town in England, but by the time we meet Gesine, she’s already endured six years of rude cabdrivers and packed subway cars. Marie, for her part, is thoroughly Americanized: Whenever she and Gesine take a trip, it’s Marie who checks to make sure that they have return tickets.

Anniversaries, which dawdles day by day from August 21, 1967, to August 20, 1968, is something between a diary, an autobiography, and an exercise in free association. Many of Gesine’s entries amount to love letters to her adoptive city. On November 13, she watches a bus trapped in traffic lumbering around the cars in its path “like an elephant good-naturedly performing his dressage routine”; on March 5, she discourses, in awe and horror, on the singular indestructibility of the New York cockroach. Gesine and Marie’s apartment is on Riverside Drive, where Johnson lived during his American sojourn, and Gesine lavishes attention on the architecture, history, and inhabitants of the Upper West Side. “For half the year, the sound of cars from the highway along the Hudson is filtered through leaves in the park, and except during rush hour Riverside Drive carries only local traffic, it is empty and noiseless at night until six in the morning, when the first people will drive to work and the hollow whistles of the railroad under the hills of the park will force their way into our shallow sleep,” she informs us. “This is where we live.”

Johnson’s friend, the poet and critic Michael Hamburger, remarked that the novelist made New York “his own by studying it with a minuteness peculiar to him.” Johnson’s observations are indeed possessed of a peculiar, sprawling omniscience. His opus belongs in the canon of encyclopedic, modernist German-language tomes like Berlin Alexanderplatz and The Man Without Qualities, and it allows itself divagations on everything from the prevalence of the color yellow in the American visual landscape to the subtleties of Hungarian politics. Gesine, an inveterate if critical reader of the New York Times, provides anxious catalogues of events both local and global: the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the robbery of a nearby store, the arrest of a Mafia leader. Her meditations are dense with diatribes—so dense with diatribes that they begin to try a reader’s patience—against the Vietnam War, which she likens with great sanctimony and little subtlety to the Holocaust.

But Johnson’s heroine is alive to the dangers of hollow outrage and dry documentation. On the wall of the apartment, Gesine hangs a “photograph of a California housewife who received a telegram telling her that her son had died in Vietnam and then sat down again for the photographer, pretending to read it.” Unlike her borrowed reportage about the atrocities in Vietnam, her direct accounts of Nazi and Soviet brutality are relentless and rending. Some are journalistic. Ilse Koch, wife of the commander of the Buchenwald concentration camp, “ordered the killing of tattooed prisoners and made lampshades, gloves, and book covers from their skin and bones.” After the war,

the dead washed up on every shore of Lübeck Bay, from Bliestorf to Pelzerhaken, from Neustadt to Timmendorf Beach, into the mouth of the Trave, from Priwall to Schwansee and Redewisch and Rande, even into Wohlenberg Cove, as far as Poel Island and the other Timmendorf. They were found almost daily.

Yet “we ate fish from the Baltic. The Germans eat fish from the Baltic to this day.”

Johnson is at his best when he personalizes an aching, anonymous history. Anniversaries’ engagements with the past can be palpable and piercing. A ten-year-old Gesine clutches the baby of a family friend during an air raid in 1943:

Immediately after the first impact there was mortar dust filling the air like flour. There was a hole in one of the side walls of the basement. The lights went out. Gesine heard the baby screaming, felt her way over to him, and ran back to the hole in the wall with him, holding the bawling creature up to the air. . . . The baby’s head hung back at a horrible angle. She knew that wasn’t right. She was scared because the baby was only whimpering now.

After the war, Gesine’s grandfather is hauled off by the Red Army. His wife runs out of the house “wailing and wildly swinging a bulging travel bag,” as if he’d have occasion to use it. Perhaps most harrowing are the travails of Gesine’s father, who worked for the resistance as a British spy during the war but angered the Soviets in its aftermath. His ordeal in Fünfeichen prison camp—where Johnson’s father, a Nazi, died—is amorphous with monotonous pain: “He had lain too long in his own filth, unconscious or asleep or whatever it was.”

Gesine often drifts into remembering, dedicating entire days to discussion of Mecklenburg dishes she misses or classmates she hasn’t seen in years. Her reflections bear no relationship to the days on which she dreams them up: The distant events she recalls occurred at different times of year than do her acts of reminiscence. Yet many of Gesine’s missives are no more than intimate tracings of the shape of her routines: her daily dealings with the taciturn man at the newspaper stand, who saves her copies of Der Spiegel; her tea with lemon from Sam at the deli downstairs; her deadening job at a Midtown bank, where she morphs into robotic Employee Cresspahl. Anniversaries is repetitive and incantatory, but isn’t that what life is like? The taking of the subway, the making of the grocery list, the ritualistic reading of the New York Times. On Saturday—South Ferry Day—Gesine and Marie ride the ferry to Staten Island and back. They do this over and over. Isn’t that how something becomes not just familiar but dear?

Anniversaries is less a work of plot than a map of human relationships. There are incongruous incursions of story, as when Gesine and Marie have to rescue a friend writing a book about mafiosi who’s been kidnapped by his subjects. (“I wish you’d hurry up,” Marie tells his captors. “Tonight’s a school night.”) But for the most part Gesine is preoccupied with her huge cast of friends and acquaintances. She warily loves and finally consents to marry D.E., a physicist and fellow German émigré. She tolerates the American overfamiliarity of her slick boss, Mr. de Rosny. She lunches with her cheery, chatty colleague Amanda, and takes weekly Czech lessons with the slow, solicitous Professor Kreslil, a relic of the Old World whose mouth collapses inward because he cannot afford dentures. With her neighbor Mrs. Ferwalter, an Auschwitz survivor, she plans a party for Marie. And the past pushes back into the present again. “The really bad thing was: that the Germans forced the Jews to kill each other. Shove relatives into the fire still alive,” recounts Mrs. Ferwalter. “So it’s agreed, yes, the cookies for the children’s party I will bring, Mrs. Cresspahl?”

Most movingly of all, Gesine recalls her family, narrating her genealogy to Marie and sometimes herself. Her father, Heinrich Cresspahl, was a master carpenter. Her mother, Lisbeth, née Papenbrock, was a member of the landed gentry whose gentle piety gave way to fanaticism during the Nazis’ ascent to power. She tried to drown and starve young Gesine and asked the pastor’s wife whether suicide was explicitly prohibited by the Bible. Anniversaries is often difficult to follow: It demands an involved knowledge of German, Soviet, and American politics and a careful attention to what seem like marginal characters, who are apt to disappear for several hundred pages only to crop up again. Its content, in contrast, can be ethically easy. All of its protagonists are implausibly brave: Gesine’s father works as a British spy, and Lisbeth slaps a Nazi in the face when he shoots a Jewish child. Afterward, she burns to death in a fire that might have been a suicide but might have been another Nazi murder.

The losses are unremitting, and they, at least, seem real. Gesine’s uncle Alexander—“no matter how often he threatened to refrain from stroking their hair, never once did a child have to ‘go to bed bareheaded’”—dies fighting in the war. Her aunt Hilde—who “was capable of running all the way to the woods after a child who’d forgotten her sun hat”—is killed by strafing fighter planes. Brüshaver, the local pastor, delivers an enraged sermon cataloguing early Nazi crimes and is dragged off to a concentration camp. Marie’s father and the love of Gesine’s life, Jakob, is hit by a train before Marie is born. “Up in the shimmering air,” writes Gesine, “that’s where I lived with Jakob.”

But Anniversaries is not a bleak book. Despite all that she has lost, Gesine is joyful, and her prose is frequently buoyant. The sea off the North German coastline has “rummaging” waves. In May, in the countryside, Marie enjoys “sunburn weather.” When Gesine labors on a farm in the early days of Soviet rule, she “dreamed gray and white and yellow.”

Johnson’s work is skeptical of its own fastidious fact-gathering. Gesine describes, in vivid detail, a picture of the Cresspahl family before admitting, “I never saw that picture.” Distraught, she pens a letter to a psychoanalyst confessing that she hears the dead. “They draw me into situations I wasn’t there for, which I in no way could have grasped with an eight-year-old’s or fourteen-year-old’s mind,” she writes. Thinking back to a high school class on the novelist Theodor Fontane, she remembers that her teacher asked, “Who is the narrator? How does he conduct himself performing this activity? Was he present at all the events that have taken place? Would those involved have wanted that, or allowed it? When are they outside the range of his observations?” Marie asks similar questions, protesting that the details of Gesine’s life story are “too contrived, like a novel.” Of a notebook that was burned, she asks her mother, “How do you know about it?”

How does Johnson know about it—about everything? How does he absorb so much so hungrily? His writing is inhuman, godlike in its immensity. Despite Marie’s protestations, her mother’s memoirs are nothing like a novel. They are so comprehensive they spill over their edges and into life itself. Finishing Anniversaries is believable, too. After so many months and so many pages, it felt like one more loss, one more exile, one more irrevocable expulsion. It is one more city where we cannot stay.

Becca Rothfeld is a Ph.D. candidate in philosophy at Harvard.