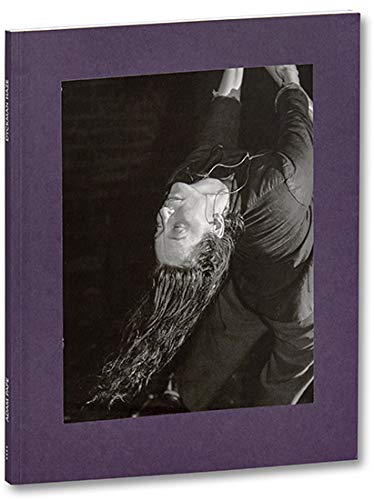

I turned Adam Pape’s new book of black-and-white photographs, Dyckman Haze, over and around several times before I was sure where to begin. Identically sized images of indeterminate orientation appear on both the front and back covers, neither accompanied by a title. One is of a dark cistern; in the other, a person of ambiguous gender folds backward, possibly mid-fall, long hair streaming toward the bottom of the frame. It’s unclear whether this is a moment of fear or of ecstasy.

Many of the images are like this, and the book itself seems to revel in a spirit of nondisclosure. There is no introductory text. The only concrete reference is to the landmark Dyckman Street (numerically equivalent to West 200th Street), which divides the historically Latino neighborhoods of Washington Heights and Inwood and occupies a vital (and to many, sacrosanct) place in Manhattan’s cultural imaginary; the street’s northernmost section crosses Fort Tryon Park and Inwood Hill Park, where many of the photos appear to have been taken. “Haze” is also the name of a potent strain of marijuana, famous in the Heights—a fact that seems relevant to the images’ loopy performativity.

Pape’s selections blur the edges between candid and posed, actual and mythical, resulting in lots of small moments of tension that somehow don’t add up to anything. One of the first photographs frames the silhouette of a waterfront high-rise with leafy branches. The full moon appears from behind the building in a cartoonishly perfect sphere. A few pages later, a person is visible from a distance, back to the camera, fleeing as if from a crime scene. In another image, a shirtless teenager wearing a gleaming chain is either putting on or taking off a track jacket. A scar curves around his right pectoral and his boxers peek over sagged Balmain jeans. His transitory expression is hard to read; the snap has the look of a B-roll candid that was never supposed to be shared. In another, a man’s face levitates just above the ground. The people in these photographs are often mid-movement, and none make eye contact with the camera. Skunks and raccoons, as prevalent as human subjects, spring from the shadows. In some images, stark, sinister lighting evokes Weegee, while in others rich gray scales and carefully calculated tableaux render a bucolic sublime.

The photographs, I learned from a single sentence on the book’s penultimate page, were taken by Pape (who is originally from Smithfield, Virginia, and received his MFA from Yale in 2016) between 2012 and 2018, in the aforementioned parks. With additional research I also learned that they were staged. Indeed, these images have a powerful specificity. Bare arms reveal that it’s summertime uptown. You can almost feel the thickness of the air and are reminded of night’s particular thrill—of taking risks but also being subject to them. Yet the disorientation I felt at first remained, creating a persistent eeriness. This eeriness is, at last, suggestive of fears and fantasies each of us carries about who and what might emerge in the dark; the threat of being unknowingly observed. But the images also evoke the specific places they were taken—territories in the throes of demographic dispute and the existential uncertainty of gentrification. Pape’s photographs reveal both the promise and the precariousness of public space. On a hot summer night in the park, realities converge and collide.