Etel Adnan has two desks. One for writing, the other for painting, they face opposite walls of the quietest room in her Paris home. When she finishes a painting she hangs it over her writing desk to dry. For half a century, Adnan has been revered as a titan of Middle Eastern literature and a beacon of avant-garde poetry. As a writer Adnan is beyond categorization, equal parts philosopher and journalist (she toiled for years as the culture editor of a leading French-language daily in Lebanon); her two dozen books of poetry and prose plumb subjects such as war, exile, terror, love, divinity, and the spring. She describes the world around her—the moon darkening at dawn; the devastation of her native Beirut by decades of war—with an unyielding lyricism that glides seamlessly from Sufic aphorism to steel-nerved reportage. We’re all the contemplatives of an ongoing apocalypse, she has said. From her long poem “Beirut 1982”: “Let us not hurry to our / Doom / let us stop and look at the Sea.”

Adnan began painting in 1959, though her signature bold abstract landscapes only exploded into the popular consciousness seven years ago, around the time that her work was exhibited as part of Documenta 13. Gemlike in their swaths of magic-hour hues, Adnan’s small paintings, typically completed in a single sitting, often refer to a sea she has seen or a mountain she has known. There is a snapshot quality to the scalloped peak of Tamalpais—the California summit she lived in the shadow of for years—as it rises again and again from the middle distance of her compositions.

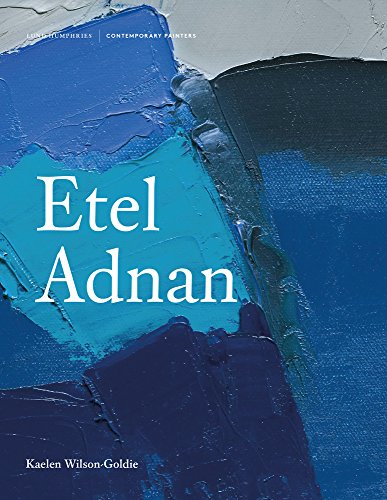

The grandness and brutality of Adnan’s writing is not irreconcilable with the bright, meditative pleasure of her paintings. In a new survey of the artist’s work, Etel Adnan, critic Kaelen Wilson-Goldie nimbly thinks across and between Adnan’s fraternal endeavors. Her descriptions of individual works are melodic, vivid set pieces in themselves, keeping steady rhythm with the nearly one hundred reproductions woven throughout the text. In addition to historically situating Adnan’s painting (“she names her own lineage in the colors of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, in the obsessions of Picasso and Cézanne”), Wilson-Goldie incisively charts each subtle shift in Adnan’s oeuvre to a biographical correlate. She also muses keenly on the metaphysical channel between Adnan’s images and words.

“Poets are deeply rooted in language and they transcend language,” Adnan has written. The question of what that looks like, and its potentially talismanic effect on others, is central to Wilson-Goldie’s deep reading of Adnan’s visual work. As the critic observes, “With sustained attention, her paintings may actually change you. They may save a world you have known.”

Adnan has a new book of poetry, Surge (Nightboat Books, 2018), which is alluded to but not cited in these pages. I would have loved to see at least one of Adnan’s poems reproduced alongside a painting, so that it might trouble the notion of disparity between forms. As Adnan writes in Surge, “So mountains are languages and languages are / mountains. / We speak both.”