LIKE MUCH OF THE READING WORLD, I rejoiced when Marlon James published his third novel in 2014. A Brief History of Seven Killings told, in part, the story of the events surrounding the attempted murder of Bob Marley in 1976. Of course, if you’ve read the novel you know that a one-line summary of the book is impossible. (And if you haven’t read it yet, well, unfuck that in 2019.) Still, there’s a natural human instinct to narrow the world, to make it intelligible by streamlining the design. Thus my one-line summary. It doesn’t work, though, not for life and not for art. Not for the good stuff, anyway. And James’s novel sure does qualify.

I’m far from the only one who felt that way. The novel scooped up the Man Booker Prize in 2015. Making Marlon James the first Jamaican ever to win the award. He won, or was a finalist for, a whole bunch of others, too. Named a Best Book of the Year by the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Boston Globe, just to stop myself at three. Though the list probably goes to a dozen or more. I read those reviews when they came out and appreciated how much the reviewers got right, highlighting the book’s historical insight, its sweeping cast, and the stylistic swagger that made every damn page vibrate.

As Zachary Lazar put it in his New York Times review: “It helps that James . . . is a virtuoso at depicting violence, particularly at the beginning of this book, where we witness scene after scene of astonishing sadism, as young men and boys are impelled by savagery toward savagery of their own.” Later he writes, “The novel’s great strength is the way it conveys the degradation of Kingston’s slums.” Lazar’s praise, the elements of the novel he highlighted, would be echoed again and again in each review I read, and I can’t say he’s wrong. James is masterful with violence and sadism, and Kingston’s slums are vividly portrayed.

But after a while I wondered about a vital aspect of the novel that I rarely saw mentioned, let alone praised, in these reviews: the sex. More specifically, the gay sex. There’s a fair bit of it in the novel; two characters—Weeper and John-John K—are gangsters who have sex with men, and James writes about both their violence and their sexuality. But only one of these things was mentioned regularly by reviewers. Some gestured at the graphic accounts of sexual acts, but one thing I never saw discussed was that some of those sex scenes were kind of hot. Erotic, is what I mean. Not sweet, not sentimental, but carnal and complicated, disturbing and arousing. And, importantly, they were thematically coherent with the rest of the novel, considering questions of power and betrayal and self-understanding.

But I saw no room for that reaction in the critical discussion in newspapers and magazines. I’m drawn back to that human instinct to narrow, to streamline; maybe the erotic aspect simply didn’t fit their concept of a Yardie gangster tale. You could read through the vast number of reviews of this book (including lots of them on Goodreads; I know ’cause I looked) and not have the slightest idea about the novel’s erotic elements, or the book’s genuine sense of humor. Those aspects, to name just two, have been sanded down, smoothed away. This doesn’t hurt the novel, I guess—those elements remain in the text—but this tendency still strikes me as a problem, a kind of erasure. A book exists on the page, but it lives in conversation. What does selective silence do to a novel, and to its readers?

James’s first novel, John Crow’s Devil, is the story of a battle for a town’s soul. There I go, doing it again. Nevertheless, the basics are this: In a Jamaican village called Gibbeah, two religious figures battle for dominance of a church and, by extension, the people. It’s Bligh the Rum Preacher—the drunken old guard—versus Apostle York, the fiery newcomer. Right from the start of his literary output the hallmarks of a Marlon James novel are there: a sense of history and locale; an enormous and varied cast; and an enviable linguistic brio. And yet, for all that promise, John Crow’s Devil collected seventy-eight rejections before being published by the astute folks at Akashic Books.

James’s second novel, The Book of Night Women, a novel I could never praise enough, concerns a Jamaican sugar plantation and the history of horrors faced, in particular, by the Black women there. (And, in some cases, perpetrated by them, too.) The central character, Lilith, helps foment an uprising that staggers in its retribution. I wouldn’t claim the novel felt “bigger” than John Crow’s Devil, but it certainly suggested a greater mastery. No difficult second novel for Marlon James, then.

Here, as in the first (and the third), reviewers found the book brutal and grim and violent. “Not a light read,” as a Goodreads reviewer suggested. And yet in this novel, too, there was intimacy. (I would note that the relationship between Lilith and the Irish overseer, Quinn, was at least mentioned, and favorably, in reviews.) The Night Women of the title, six Black women, slaves, who are the leaders of the planned uprising, display wrath but also a degree of tenderness, the kind they have available under such circumstances. But still the reviews of these novels returned to those weighted terms: dark, disturbing, and violent.

If human beings tend to simplify, not all writers are simplified in quite the same way. The deeply misanthropic tendencies in writers like David Foster Wallace or Jonathan Franzen rarely seem to limit critical conversations about their work. Instead, those writers are described as encyclopedic or philosophical. (Rather than preening or melancholy, for instance.) Don’t get me wrong, I think that even those positive descriptors do a disservice, but not all prisons are the same; some are minimum security, others are supermax. If we’re talking about Black literary writing—from the US or abroad—what’s praised, highlighted, and rewarded can become dispiritingly predictable. Black pain and violence are regarded with high seriousness. Black misery is medal-worthy. This is especially true when the critic isn’t Black.

Which leads me back to A Brief History of Seven Killings and the absolute joy I felt when James won the Booker. (And a year later when Paul Beatty did the same.) James’s novel, and his win, felt long overdue. Not solely for him, but for the kind of Black books he’s written. Right from the jump, back in the John Crow days, James embraced the fullness of Black life in Jamaica and, by extension, around the world. I suspect that’s partly why his first novel garnered so many rejections. Those editors simply weren’t ready for that shit.

How glorious, then, to see the critical establishment recognize his project, reward it, while the man is still alive. With this storm of accolades, James had, in a sense, established his own territory. He could reasonably expect to tell his stories—the glorious and the grim—and be read, recognized, discussed. He might, conceivably, churn out more of the same, with nominal variation, and do real fine for the rest of his writing life. But instead what does Marlon James—a contrarian of the first order—decide to do?

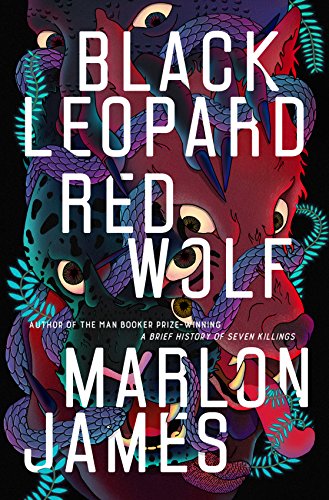

This dude goes and writes a fantasy novel.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf is the story of a man named Tracker, who joins a team sent to find a missing child. By now we both know that summary is a lie. On the first page Tracker, the narrator and protagonist, asks a question of his jailer: “Shall I give you a story?” Of course James is also speaking to the reader. It’s a trick question, though; a good story can be the best way to tell the truth.

The novel stands as an epic quest—with great deeds and horrors and all one would expect of such a tale—but there’s also a way that every page reads like a corrective to what’s still too often left unstated about the fantasy genre: If literary fiction is quite white, fantasy is even whiter still.

James’s novel has been billed as an African Game of Thrones, but that strikes me as too recent a reference. Instead, James seems poised to refute the commonly held idea that “high fantasy” is a synonym for “ancient European.” I’d say James isn’t going after George R. R. Martin, but after granddaddy Tolkien instead. The fantastic-quest narrative existed long before The Lord of the Rings, obviously, but that trilogy certainly cemented the quasi-European mythic past as a bedrock setting in the popular imagination. Marlon James is here to kill that noise.

With Black Leopard, Red Wolf, James reorients the reader using bygone Africa, its kingdoms and its conjuring, as his muse. And he’s a much better prose stylist than Tolkien, knowing when to let Tracker’s blustery voice take center stage and when it should become quieter, so the fantastic may dazzle us instead. Here, Tracker enters the home of a witch who cares for orphaned magical children:

Somebody had shined that clay ceiling with graphite. The woman was hanging from the ceiling. No, standing on it. No, attached to it looking down on me. But her robe stayed in place even with the gentle wind. Her dress covered the breasts. Truth, she stood on the ceiling the way I was right there standing on the floor. And the children, all the children were lying on the ceiling. Standing on the ceiling. Chasing after each other over and under, around and around, hissing and screaming, jumping but landing back on the ceiling.

I love this moment because it illustrates, in an image, what’s so exciting about Black Leopard, Red Wolf. James manages to write a fantasy novel that is both grounded and, simultaneously, playfully fantastic. This book might do his finest job yet of blending the horrific and the exquisite: There is love and lust and betrayal and faerie folk, though here they’re called Yumboes.

Some of the elements I’ve mentioned from Brief History are also here: There’s sex, there’s intimacy. Tracker has an ongoing love-hate-love relationship with a character named Leopard. To be clear, Leopard is a man who can turn into a leopard. In an early encounter Leopard makes a vague threat to Tracker, but Tracker isn’t scared. “He didn’t frighten me, nor did he intend to. Everything he stirred was below my waist.” Among all the other journeys this novel depicts, it is the story of Tracker and Leopard that means the most to me.

Recently my wife served on the judging committee for a prize that offered, to the winner, publication by an esteemed press. But the representative of the press and the donor of the prize rejected the judges’ choice, due to squeamishness. The protagonist of the book that was chosen is a sex worker—and, as you might expect, there are explicit depictions of sex. These were labeled “gratuitous,” and so no award was given that year.

The novel about the sex worker, to my knowledge, has yet to be published.

Tracker talks, at one point, of shoga men, a term for gay men: “This is not the first you have heard of shoga men. Call them with poetry as we do in the North; men with the first desire. Like the Uzundu warriors who are fierce for they have eyes for only each other. Or call them vulgar as you do in the south, like the Mugawe men who wear women’s robes so you do not see the hole you fuck.”

Imagine that a paragraph like this might be deemed “gratuitous” by an editor, a publisher, a reviewer. The kind of thing that’s easier to edit out or ignore. What happens, then, to the human beings Tracker is describing? If you are never mentioned you might come to believe you don’t really exist. This is true whether we’re talking about shoga men or the place of the nonwhite person in the pages of fantasy.

The tendency to reduce is human, but that doesn’t absolve us. Literature, no matter the genre, is meant to remind us that we might aspire to see and understand and embrace more than we’re naturally inclined to. The brilliant and bold Marlon James has already done this in one arena and now he’s poised to pull it off in another, tearing down some of the pillars of fantasy so the temple can be expanded and rebuilt. He isn’t alone; authors like Sofia Samatar, Kai Ashante Wilson, and Fonda Lee, to name just a few, are writing with a fullness that refuses reduction. They will not be stopped, and their readers are finding them. Really, the question is whether the critical establishment can catch up. I want them, and their voices, to be a part of this ongoing conversation about literature, what it is and what it’s becoming. As Tracker is fond of saying throughout James’s novel, Fuck the gods. This is going to be fun.

Victor LaValle’s The Changeling (Spiegel & Grau, 2017) won the American Book Award.