Imagine Manny Farber’s double career—unparalleled vernacular-modernist movie critic and tenaciously evocative, obliquely iconographic painter—as a board game. Dub it Polyopoly, an incessantly self-revising, once-upon-a-time-in-America contest of chance, mental play, and adventure. Like the kindred gamesmanship of filmmaker-photographer-writer Chris Marker, Farber’s output remains elusive: It’s hard to tell whether he was so far ahead of his time he overshot it or so far behind he caught up with it on the rebound.

The intricate sprawl of Farber’s pictures wasn’t coded autobiography but homebrewed psychogeography: the contents of a mind in perpetual motion, with personal touchstones spilled across tabletops or Post-Imp panels like noetic maps. Man-made and organic items are positioned as though by a model railroader (or, in the later pictures, a scent-drunk gardener), painted from an overhead perspective like in a crane shot. This scale-shifting, tangent-happy icontopography consists of votive tokens and tchotchkes: Aside from the aforementioned railroad tracks, Farber’s paintings are brio-infused bricolages of postcard imagery, toy-storybook illustrations, scribbled notes, domestic detritus, and fresh vegetables/flowers/air. Film-inspired works like Honeymoon Killers or The Films of R. W. Fassbinder are populated with murderous miniature Shirley Stolers (collect the full set) or come with leatherboy action figures, toilet/stove/TV figurines, and one lonely fox.

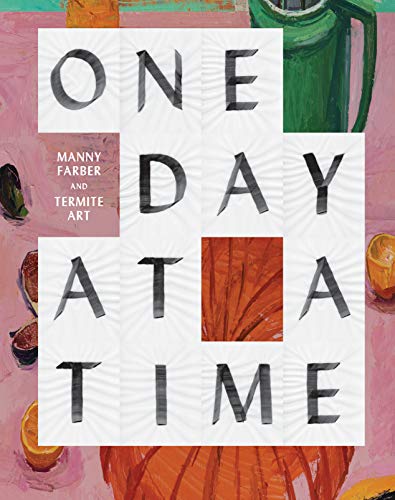

Nicely jam-packed but spacious enough to give the art breathing room, One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art is a summary of the current exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, devoted to the Farber aesthetic, lovingly pegged to his immortal critical sideswipe-broadside, “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” (1962). Along with Farber’s establish-ment-averse work, curator Helen Molesworth rounds up moderately offbeat painters, photographers, and assemblagists—termites, all—who carry on the eternal struggle against the rampage of “white elephant art.” Farber’s concept here is boiled down to the idea of small, self-contained omnivores nibbling at the bloat of overweening significance, billionaire-hipster art marketeering, and Thanksgiving Day Parade Dumbos. Numbered among Molesworth’s cast of gnawing-termite types are Marker, Nancy Shaver, Moyra Davey, Wolfgang Tillmans, Dike Blair, Beverly Buchanan, Fischli & Weiss, and, naturally, Farber’s indispensable partner, collaborator, and tough-minded inspiration, Patricia Patterson.

Farber’s paintings don’t exactly suggest a posse in tow, but Molesworth’s mix-and-match bunch effectively represent the vivaciously mundane side of the “eager, industrious, unkempt activity” termite art prized most: surreptitiously crossing borders and dodging prestige labels. Melding precision craft and motley arrangements, Farber’s “termite-tapeworm-fungus-moss art” is tied to a questing domesticity that finds infinity in—and under—everyday objects, gestures, and conditions. Besides possessing a firm grasp of heterogeneous disciplines and Farber’s relation to them, the curator also has the perfect name for the job. Who better to organize this show than someone called Molesworth?

Farber’s paintings could be as cluttered as the lively, circular wheel-of-misfortune Marguerite Duras, Possibly (1981), ravishing as About Face (1990; sunflowers drunk on their own engorged gorgeousness), or enigmatically instructive as “Passive is the ticket” (1984). The latter is a five-foot rectangle, three crisp panels littered with asparagus spears, a tray of eggs, thinly scrawled notes (like “This is not debris: Each of the items means something”), a toy truck, and a pot of turnips and brown potatoes. The Duras number’s a preteenage riot of erotic drawings, trestles, dolls, open books, paper, rulers—a child’s garden of innocent perversities. Rohmer’s Knee, from 1982, takes this centrifugal circularity into a Vertigo-inducing trance—Éric Rohmer’s dutiful bourgeoisie suddenly indistinguishable from Hitchcock’s playthings and corpses.

The artists orbiting Farber’s negative-space station suggest muted offshoots, decorative third-generation pollinations, or mere drifting spores that snatch body parts or smaller organs instead of hijacking the entire being. They approximate the Farber totality by various means: The studious presentation and tactile directness of Marker’s photo portraits could be strings of a DNA chain linking ordinary reverberant humanity across decades and continents. Tillmans’s summer still life (1995), a shot of upscale items “casually” spread on a windowsill with the odd-coupling meticulousness of Felix Unger tidying up after William Eggleston, balances on the fine edge between depicting a life of leisure and a postmodern postmortem. Catherine Opie’s Handbag Reflection (2010–11) has a creepy bourgeois-plebeian air, a shelf of purses caught in an ornate mirror, a sense of decomposing privilege in full rigor mortis.

Objects like Buchanan’s wondrous little painted-wood models of houses, shacks, and cabins (striking domiciles for a clan of Abstract Expressionist hillbillies) or Davey’s row upon 12 x 18″ photographic row of Empties could practically be additions to the running bulletin-board-in-a-china-shop of rescued images, notes to self, and enchanted scrap that mutates across Farber’s richest period (roughly 1975 to 1986). One Day at a Time traces an intriguing trajectory, picking up after he decamped from the fringes of the New York abstraction scene (where he made more noise as an underground legend of a film critic than as a painter). Landing in 1970 in the visual arts department at the University of California, San Diego, he gave the doctrinaire the slip by introducing figuration via modest objects. The “American Stationery” and “American Candy” series—nodding to small-town Arizona drugstore-shelf roots—were test runs for the more prodigious “Auteur” works, which are not about anything as obvious as “genius” per se, but are rather a slippery composite of telltale signs, Japanese-print bows, bite-size morsels and gunsels, and rude asides.

The point of Farber’s aesthetic was restless motion bound to a meditative component: constant reevaluation of the materials at hand, a refusal to turn the work into a brand. Hence the shift to the lean-silhouette lank of work like Under the Hammer (1984). This piece pares his allover approach down to two thin figures on a big, white background—a bright cut-out cowboy with a hammer twice his size crushing his forehead. It’s as endearing as a Tom Mix western and as disconcerting as an illustration for Kafka’s Amerika.

By Story of the Eye (1985), the natural world—in the kudzu-ish form of fruit and fish—has taken over the pictures, pushing out the cultural referents and private allusions. Though, in a way, all the phantom threads from film and art that bind the prior designs are little pieces of artificial life transformed into something as natural as a coral reef. Farber’s late paintings aren’t a radical break; more like a new way of life, making a home of the world in all its contradictions. This has always been at the heart of his conceptions: a search for ways to thrive on internal and external—emotional and formal—tensions. Painting and movies were two halves of a field Farber ranged over like a swivel-hipped halfback. Instead of scoring touchdowns, he wanted to find the thousand ways a performer or a brushstroke or a provisionally random object might shake up the frame, pull focus, break character, turn the up- or downbeat around and back in on itself. Everything from halved figs to listless eggplant functions as a character actor in Manny Farber’s stock company, Cézanne as seen through the prism of Preston Sturges. (Vice versa from the film criticism.)

In his later pictures, Farber’s embrace of organic components, like a gardener’s green thumbprint, is only the most obvious of the countless ways he was indebted to Patterson. And just as obviously, the nurture was mutual. Perhaps nurture itself is the real subject of all those vegetation-saturated paintings (the most touching of which is Ingenious Zeus, 2000, with akimbo photobooks opening like blossoms alongside leeks and white roses). In an obit, Robert Walsh described the couple’s symbiotic union: “With the paintings, it wasn’t just that they talked about them. . . . He literally would say, ‘What should I paint next?’ Or ‘What should go here?’ She would often tell him when to stop a painting, that it was basically finished and he should let it go, whereas he might want to fiddle a little more. Even those notes in the paintings are often actually Patricia’s words that he appropriated and used as a message to himself.”

Here marriage is a floating process where, as with Martial Solal and Lee Konitz’s jazz duets, the partners are absolutely distinct but in an overlapping dialogue (equally applicable: McCabe & Mrs. Miller, both the movie and Farber’s elliptical painting of the same title). Ideally, you never can tell where one partner leaves off and the other begins; it’s a “fierce act of engagement,” a phrase Patterson used about Farber’s writing that covers all the bases when talking about his art and life. Lessons (history and otherwise): Can the superlatives. Think praxis. Remember the bit players, the small-scalers. Avoid the main roads. Stick to the meat and raw materials. And keep a Laurel & Hardy routine in your eye’s mind at all times—one set of hands putting a thing together just as fast as the other can take it apart.

Have fun.

Howard Hampton is the author of Born in Flames: Termite Dreams, Dialectical Fairy Tales, and Pop Apocalypses (Harvard University Press, 2007).