EVEN BEFORE her death from myocarditis in 2005, Andrea Dworkin was more read about than read. She had become less a public thinker than a symbol, an embodiment of feminism’s missteps and excesses. The right parodied her with the viciousness reserved for misogyny, mocking her overalls, frizzy hair, and excess weight. The left aggressively disavowed her, with other feminists going out of their way to contrast her opinions with their own. Almost fifteen years after her death, her exile from the sphere of acceptable political thought is near-absolute. It is still more common to see her ridiculed than cited.

Much of Dworkin’s unpopularity was her own fault. She held inflexible opinions on pornography and sex work that have fallen dramatically out of fashion, and she made terrible tactical missteps in pursuing her vision of a world without the sex trade. It’s true, too, that she wrote with a passion and anger still uncommon in women, and she directed some of her fiercest critiques at fellow feminists who had once been her friends. But part of her downfall was simply a matter of timing. Dworkin was twelve years younger than the woman she considered her hero, the second-wave feminist critic Kate Millett, and she found herself expanding on Millett’s ideas of structural misogyny a half generation too late. She published her most influential books not in the late 1960s but in the 1980s, just as the second wave was dissolving into factionalism and backstabbing, and as an emergent conservative groundswell was taking hold and preparing to sweep away their gains. By the end of the decade, high heels, lipstick, and sex positivity were in; Dworkin—and her gruesome, angry characterization of sexual violence—was decidedly out.

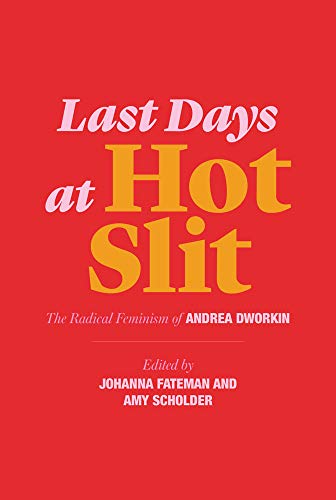

Last Days at Hot Slit, a collection of Dworkin’s writing edited by Johanna Fateman and Amy Scholder, is an invitation “to consider what was lost in the fray,” as Fateman writes in her moving introduction. Hot Slit contains excerpts from all of Dworkin’s major books as well as previously unpublished material, including letters to her parents, university lectures, and a portion of an unfinished end-of-life autobiographical manuscript called My Suicide. The style is strident, enraged, and the conclusions are often stark, bluntly phrased, and difficult to read. Dworkin had reason to be angry: Her life was marked by the kind of male violence that is disturbingly common yet consistently goes unacknowledged. In 1965, when she was eighteen and a student at Bennington College, Dworkin took part in an anti-war demonstration in Manhattan and was arrested. In jail, she was subjected to a violent gynecological exam that I have no word for other than rape. Her decision to write and testify about it caused enormous distress for her parents, who were upset not only at what had happened to their daughter, but by her choice, incomprehensible to them, to talk about it publicly.

Three years later, Dworkin moved to Amsterdam and married a Dutch man she met in an anarchist group, a man with strong political commitments who treated her as an intellectual equal, at least at first. Soon after the wedding, he began to beat her—burning her with cigarettes, hitting her legs with a wooden stick, grabbing her by the hair and slamming her head onto the floor until she lost consciousness. She left him in 1971, when she was twenty-five, but he followed her, finding her in the homes of friend after friend and threatening her, beating her. In her memoir Life and Death, she writes, “I remember the pure and consuming madness of being invisible and unreal, and every blow making me more invisible and more unreal, as the worst desperation I have ever known.” In Europe, she had started doing sex work to earn money, and she would come to see every trick as a rape, the sex not fully a choice she was able to make freely but a necessity endured under the threat of being invisible and unreal.

These experiences had a formative impact on Dworkin’s thought and would shape all of her subsequent work. Her first book, Woman Hating, a broad accounting of historical and literary misogyny, published when she was twenty-eight and written in the furious, electric style that characterizes a newfound intellectual passion, was, among other things, an attempt to make sense of what she had just lived, to place it into a larger political framework. She would continue this labor in Pornography: Men Possessing Women, her 1981 anti-porn opus, which positioned pornography as a kind of propaganda serving to indoctrinate men into ideas about sex and women that encourage violence, and in Intercourse, her infamous and widely condemned study of heterosexuality in literature, frequently misread as claiming that “all sex is rape.”

Dworkin has a reputation as the quintessential overzealous radical, imperiously steamrolling over the fault lines of race, of class, of history in her call for universal sisterhood. Yet the writings collected here reveal as much attention to what divides women as to what binds them. Like many feminists of the second wave, Dworkin was prone to facile, unthinkingly broad characterizations of misogyny, but Woman Hating begins with the acknowledgment that a woman might be endangered and exploited in more ways than one. She and her white, middle-class peers, she writes, were not only victims but “oppressors of other people, our poor white sisters, our Black sisters, our Chicana sisters. . . . This closely interwoven fabric of oppression . . . assured that wherever one stood, it was with at least one foot heavy on the belly of another human being.” In Right-Wing Women, she wrote with sympathy about the lives of women in the Reagan-era conservative movement, but also of how easily their vulnerability and fear were transformed into violent contempt, of how they recoiled with homophobia and anti-Semitism when they realized she was Jewish and gay. For Dworkin, to be a woman in the country she never stopped calling Amerika was to be in a state of emergency; but this did not make womanhood a singular emergency, let alone the most acute or morally urgent in a woman’s life, the “first identity, the one which brings with it as part of its definition death.”

This determination to grapple with the divides between women reflects a tendency that’s characteristic of Dworkin: to look straight at those questions in feminism that are the most delicate, the most painful, where women have the most to lose. Her fearlessness, her willingness to keep looking at what others can’t bear to see, is there in what is perhaps the book’s most devastating piece, “The Rape Atrocity and the Boy Next Door,” delivered as a lecture at a number of East Coast colleges between 1975 and 1976. In it, Dworkin painstakingly enumerates the cultural attitudes and assumptions that encourage men to rape and discourage men and women alike from understanding sexual violence as harm. Coercion, force, and the overcoming of women’s unwillingness are fundamental plot points in our stories of sex and love, she says, and they have become so fundamental that it is difficult to see around them, difficult even for women to know when they are really unwilling and when they are playing their mandated part of the coy damsel. This, she says, is how rape became not an anomaly, but the fulfillment of a foundational cultural narrative. Rape is not exceptional but common, committed by common men acting on common assumptions about who men are and what women are. “The fact is that rape is not committed by psychopaths,” she wrote. “Rape is committed by normal men.”

After Dworkin delivered this lecture, women would come up to tell her about their own rapes. She became a repository of women’s pain, of men’s infliction of that pain. It was knowledge that she found unbearable. “I stopped giving the speech,” she later wrote. “I thought I would die from it. I learned what I had to know, and more than I could stand to know.” This, I think, is part of why Dworkin remains so unpopular. She wants us to do what she did for the women who spoke with her after her college lectures: to look dead into the fact of what it means to be a woman in this world, into the pain and violence visited on women because they are women. It requires us to know more than we can stand to know.

Dworkin sealed her fate when she first became involved in anti-porn organizing in the mid-’70s, lending her support to groups such as Women Against Pornography, Women Against Violence Against Women, and Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media. These groups slowly became more militant, moving from Take Back the Night demonstrations to legislative interventions against porn. In a dramatic failure of judgment, in 1983 Dworkin and the feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon drafted the Antipornography Civil Rights Ordinance, a measure that sought to restrict pornography on civil rights grounds. They partnered with religious and social conservatives to promote the law in several local jurisdictions, working together to try to get it passed. It was this alliance with the right wing that caused Dworkin’s fellow feminists to finally reject her outright. How could she get in bed with the people who wanted to ban abortion, criminalize her fellow lesbians, force her sisters back into the kitchen? It was a betrayal that many feminists would never forgive.

In her writings against pornography, Dworkin’s central argument is that porn acts as a tool of mental conditioning: that it taints men’s minds and contributes to an understanding of sex as antagonistic, violent, and inextricably bound up with women’s subjugation and humiliation. But if porn narrows men’s minds about what sex can be, her own objection to it narrowed Dworkin’s understanding of the larger feminist project. In her attempts to wield the power of the state against pornography, Dworkin was not a trial-and-error explorer, fumbling her way toward justice ad hoc. She was a top-down dogmatist. And in this way, at that moment, she had betrayed the imaginativeness of her own vision.

Amid the fiasco of the anti-porn ordinance, feminists who opposed Dworkin’s anti-porn activism had begun to mount defenses of porn, sadomasochism, free speech, and the right of every woman to engage without shame in all kinds of consensual sex. Dworkin’s former friend, the writer Ellen Willis, used the term “pro-sex feminism” to describe this faction in her 1981 essay “Lust Horizons: Is the Women’s Movement Pro-Sex?” In the essay, Willis decries what she sees as the censoriousness and shaming attitudes of the anti-porn feminists: Why should women be told not to enjoy what little pleasure they can eke out under patriarchy? Willis is conflicted, ambivalent; she seems unsure about what porn means for women, and about whether it can really be wielded in the service of their liberation. She wants a world where women can fuck and love as true equals to men, but seems at a loss as to how to get there, how much sacrifice will be required. In this ambivalence, Willis became the perfect foil for Dworkin. Willis was unsure; Dworkin was certain. Willis asked questions; Dworkin had answers.

Yet the end of the sex wars did not bring with it the more liberated world that feminists like Willis envisioned. Instead, the nuanced pro-sex position championed by Willis gave way to a more individualistic and conciliatory approach to women’s rights—one that focused not on the second wave’s project of “liberation” but on a simpler, less ambitious, and more market-friendly idea of “empowerment.” In time, third-wave sex positivity became as strident and incurious in its promotion of all aspects of sexual culture as the anti-porn feminists were in their condemnation of sexual practices under patriarchy. The movement has spent the past three decades in a state of confusion, unable to reconcile its twin mandates of celebrating women’s sexual agency and combating men’s sexual violence. Consent has turned into a political divider, separating the parts of our sex lives that should be the subject of feminist analysis from those that should be exempt from political inquiry—what intimacies, pleasures, and pains can be analyzed, and what must be set aside behind a velvet rope. It should not be hard to say that even though women make their own choices with regard to sex, we make those choices under unfairly constrained circumstances; that even though we can and do initiate and enjoy sex, we are also more vulnerable to sexual coercion, exploitation, and violence than men are—and that when we experience these abuses, it is usually at men’s hands. It should not be hard to say that heterosexuality as it is practiced is a raw deal for women and that much pornography eroticizes the contempt of women. It should not be hard to say any of this. But it has become hard.

Dworkin, in many ways, predicted this state of affairs. Writing in 1995, in the preface to the second edition of Intercourse, she saw with clarity the ways consent had been flattened into a synonym for compliance in the aftermath of the sexual revolution, used as a way to stop women from talking about the often painful and complex reality of their intimate lives. “In this reductive brave new world, women like sex or we do not. We are loyal to sex or we are not. . . . Remorse, sadness, despair, alienation, obsession, fear, greed, hate—all of which men, especially male artists, express—are simple no votes for women. Compliance means yes; a simplistic rah-rah means yes; affirming the implicit right of men to get laid regardless of the consequences to women is a yes.”

Consent, Dworkin understood, is an essential but insufficient tool for understanding the political realities of sex. She goes beyond this framework, analyzing sex not only as it is had, but as it is depicted and imagined. Some of the conclusions her work draws are overly cynical, overly prescriptive. Others are undeniable, obvious to anyone with a feminist consciousness. When she was most fervently campaigning against porn, Dworkin expressed the hope that it would one day be banned, eradicated; she compared the anti-woman “propaganda” of pornography to the anti-Jewish propaganda of Goebbels. It’s overly simplistic, and it’s naive: There will likely never be a world without the sex trade. But it might not be much more naive than the claim that there are areas of our sex lives where feminism shouldn’t travel, where the sex we have is consensual and therefore nonpolitical.

After Dworkin published an incendiary piece about the assault she suffered in jail, an inquiry was made into the New York Women’s House of Detention, the Manhattan facility where she had been held. Her testimony was reported worldwide and led to an unprecedented public outcry over the treatment of women prisoners there. Eventually, the city was forced to close the jail; it was demolished in the early 1970s. Now the site, just outside the West 4th Street subway stop, holds a flower garden. It’s adjacent to the picturesque turret of the Jefferson Market Library. On a typical afternoon, the garden is full of straight couples. They kiss and take selfies. There is no marker of what happened.

Moira Donegan is a writer and feminist living in New York.