John Berger became a writer you might find on television because of Ways of Seeing, the 1972 BBC series that became a short and very famous book. The show presented observations now common to pop-culture reviews—publicity “proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more”—in a place (a box!) that rarely admitted critique beyond yea or nay. The book version of Ways of Seeing, which combined photos and text in a montage format, is now a staple of critical-writing syllabi. Writers like Laura Mulvey and Rosalind Krauss wrote the definitive versions of theories Berger proposed, and dozens of critics have put in decades peeling back the semiotic layers of images. Berger simply made it seem plausible that there would be an audience—possibly a big one—for this kind of thinking. In May of 2017, four months after Berger’s death, feminist media scholar Jane Gaines wrote about Ways of Seeing: “We learned from him to see that basic assumptions about everything—work, play, art, commerce—are hidden in the surrounding culture of images.”

Berger’s 1985 show for Channel 4, About Time, went in the other direction. This was the televised version of And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, a 1984 photo-and-text book about storytelling. For the opening, the most famous televised rhotacist next to Elmer Fudd wore a blue checked shirt and spent almost ten minutes telling the story of a man who wants to live forever. A faint echo of the legend of Oisín, Berger’s tale is a shaggy-dog story about trying to escape death, told in such a soothing way that Death, with his cart of worn-out shoes, becomes a cozy presence. (Several YouTube commenters think this episode works well before bed.) Much of what made Berger unique is in this segment, and the fact of its existence.

An English Marxist, anti-fascist, and anti-racist who abandoned England in his thirties was welcomed back to his homeland to create mass-market visual essays with room for long, digressive stories about drawing his dead father’s face. Avuncular and stubborn, Berger was a genuine father figure. He could be describing the punishing misogyny of a Renaissance painting while sounding like a docent herding you toward the statuary, or an elder warning you about a divot in the road.

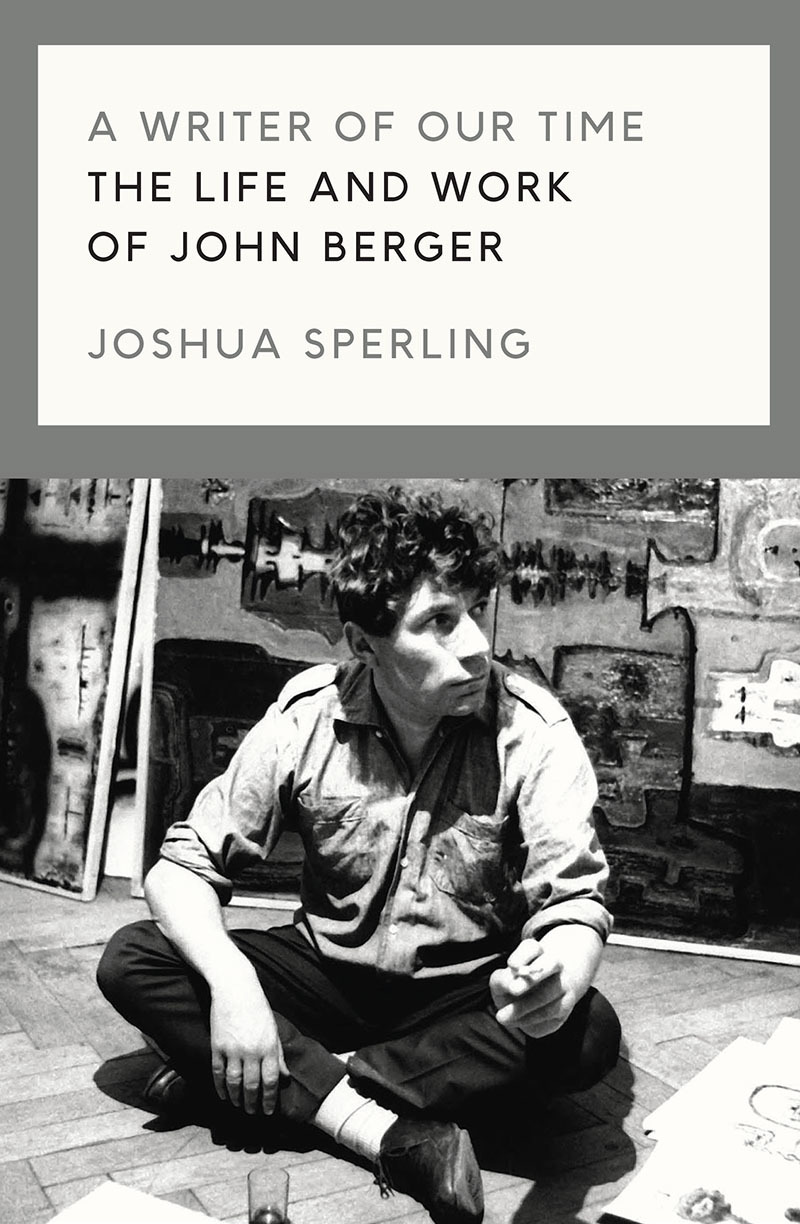

Joshua Sperling’s tight biography of Berger, A Writer of Our Time, takes stock of an easily loved author without bending the knee. (Soon, there will be another book—Berger’s archivist, Tom Overton, is scheduled to finish his biography this year.) Berger’s gaze was steady, his pace calm, his default mode genial. His mode of scholarship was not one-upmanship. Barthes and Sontag got to photography first, and Fanon wrote about migrants long before Berger. But he knew how to find a problematic area and conduct his inquiry blind to both obstacle and custom. A montage of photographs and essays? Sure, even if it’s not really a known thing beyond a few pamphleteers. Television? Why not? It doesn’t have to be fast or unsubtle. Art criticism? The classist Masons have held it long enough.

Whether or not there could be another Berger seems a less interesting question than how this one Berger happened, as his achievements are a combination of the familiar (was smart about how power relations manifest through language) and the vaguely ancient (worried, briefly, about whether or not the Communist Party would cosign his reviews). Sperling has paid close attention to Berger’s work and can celebrate him without pretending that Berger could be dropped, whole cloth, into the twenty-first century.

If you want to see exactly how Berger was of his time, go to Sperling’s section on the novel G., Berger’s other big moment from 1972. G. is a cross-cutting of voices (third-person narration, unidentified lecturer, unidentified characters) that is formally distinct from his other novels, but it’s not an intellectual departure. Berger used so many different forms—photo-essays, narrative films, documentary TV programs, drawings, reviews, memoir—but the voice is consistently generous and pedagogical. “The multiplicity of the work should not be seen as a mark only of restlessness,” Sperling writes. “It was more like an ongoing philosophical wager. How to connect fields and regions of experience far too often kept separate?”

Berger’s first novel, A Painter of Our Time (1958), used the character of a Hungarian social-realist painter to spell out the potential failures of seeing painting as direct political action. G. was no less committed to instruction, though it’s still an infinitely weird (and worthwhile) book. The main character, known at first as “the principal protagonist” and later as G, is a generally reflective cipher who flies all over Europe to do all the big sex. (Don Juan was apparently the referent.) The ambient horniness and lack of contextual detail give G. more than a passing resemblance to Ulysses, a debt that Berger acknowledged.

But Berger had to Berger, and in the middle of G., he breaks set—not that there is a traditional narrative voice to disrupt—and introduces “rough drawings” of a penis and a vulva. He then launches into a passage that could have been taken from Ways of Seeing.

Take the first [drawing]. Put the word big above it. Already it is changed, and the load increased. It becomes more specifically a message addressed tby writer to reader. Put the word his in front of big and it is further changed.

Take the second one and put the following words above it: Choose a woman’s name and write it here. Although the number of words has increased, the drawing remains unchanged. The words do not qualify the drawing or use it syntactically. And so the drawing is still relatively open for the spectator’s exclusive appropriation.

Sperling notes that G. was described by reviewers as “porn with graffiti,” along with other putdowns, none of which deterred the most famous moment of this novel’s life—Berger winning the Booker Prize. “Berger, who had been tipped off earlier in the week that he would be awarded the prize, had been on television the day of the gala to announce his plans,” Sperling writes. “He was going to give half the money, as a gesture of solidarity, to the London-based Black Panthers.” Berger’s dislike of prizes was amplified by his distaste for the award’s patron, the Booker-McConnell corporation, “whose immense fortune rested on extensive holdings in the West Indies.” Sperling describes Berger’s speech that night as his “most searing piece of rhetoric.”

After criticizing the “competitiveness of prizes,” he announced his plans to write a book about migrant workers. Then he mentioned Booker-McConnell’s “trading interests in the Caribbean,” and the poverty that forced “hundreds of thousands of West Indians” to travel to Britain as migrant workers. This did not bring out the best in Britain. Berger continued:

Before the slave trade began, before the European de-humanised himself, before he clenched himself on his own violence, there must have been a moment when black and white approached each other with the amazement of potential equals. The moment passed. And henceforth the world was divided between potential slaves and potential slavemasters. And the European carried this mentality back into his own society. It became part of his way of seeing everything.

When Berger suggests that you sit and spend time with a subject, it is a deeply literal instruction. Berger’s first collaborative photo-essay, A Fortunate Man (1967), told the story of a country doctor in the west of England, John Eskell. With his friend Jean Mohr, Berger documented six weeks of Eskell caring for members of his small rural community. The resulting book is as gentle as his Booker speech was barbed, and this kind of tonal range was Berger’s strength. (Sperling points out that in less than twenty years, Berger had managed to do an axial turn in affect, moving from finicky Communist to loopy horn-dog of the vale. “At the start of his career Berger was condemned for proposing a vision of art that sucked the mystery out of the artwork, that reduced it to a political tool,” Sperling writes. “With G. he was accused of mystification.”)

In 2005, the British Journal of General Practice called A Fortunate Man the “most important book ever written about the field.” The photo-essay that seems most ripe for revival, though, is A Seventh Man (1975), which documents the experience of migrant workers in Europe. Calling it ahead of its time is slightly insufficient, as the issues of statehood and citizenship are simply the issues of now. A Seventh Man helped start a discussion that is nowhere near finished. At the Oscars, when chef José Andrés saluted the “invisible people” who hold the world together, his words were part of the same continuum.

“If A Fortunate Man grew out of the neo-realist tradition and its extension into the documentary,” Sperling writes, “A Seventh Man was built on the newly rediscovered tradition of montage: the Marxist modernism of the left-wing film essay.” But the tendencies of the moment, as critical theory went, weighed against Berger’s attempt to channel his politics through the idea of lived experience. His colleagues on the left were not immediately convinced that this was the way to make a thorough case. Anthony Barnett, a friend of Berger’s, wrote in the New Left Review that experience “may be ‘a valid check on theory,’ but ‘the laws of motion of capitalism as a global system,’ he said, could only be grasped through ‘arguments of the abstract kind.’” Whether or not being out of sync with the Left was ultimately decisive, A Seventh Man was, as Sperling describes it, a “commercial failure.” Not, though, a failure for Berger, who consistently cited it as his favorite.

Sperling nails one of the trickiest parts of Berger’s early career, a moment of change and redirection that provides a map for the rest of his work. Initially committed to the idea of a realist painting style that combined accessibility with an explicit politics—his model for years was the Italian painter Renato Guttuso, who reads as a Continental Diego Rivera now, and less interesting—Berger eventually realized his writing was critically advanced in a way that representative oil painting of the 1950s was not. He didn’t waste time bemoaning the horse he’d bet on and, instead, revisited Cubism in the 1960s and pulled a rabbit out of a rhombus. Sperling writes:

Properly primed, cubism—though Berger himself eschewed drugs—could be like an acid trip or an awakening: a journey to a molten layer of truth. It helped not only to disperse the ego but to de-reify the visual world. It was the only art, Berger said, to have touched totalities, to have revealed this deeper substratum of perception. The flattening and fracturing of space, the discontinuity of planes within the picture, the apparent two-dimensionality of the canvas, the montage of spatial perspectives. In all this we recognize the madeness of the image (what most critics have focused on), but we also enter into a visual field that exists in a state of perpetual arrival, objects forever emerging and renewing themselves, before our perceptual faculties of organization have been able to snap everything back into solid place. “But reality is not,” Lukács said, “it becomes.” Or, as Berger wrote: “Rather than ask of a cubist picture: Is it true? or: Is it sincere? one should ask: Does it continue?”

Here is Berger’s love of the gerund, his dedication to the idea of “seeing” rather than “sight.” Perception, for Berger, is a constitutive act, and Sperling is right to find that principle in Berger’s reassessment of Cubism. “‘Seeing comes before words,’ he says at the start of [Ways of Seeing]. ‘It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it.’ Berger’s thought in this regard is spatial. Language approaches experience, but it can never replicate it or take its place. There is in each of us a vocabulary of what we have lived that can never be fully expressed. Therein lies not only frustration, but wonder.”

Berger’s later years are harder to track because he avoided large writing projects. (His undertaking was living itself, which he did in the French village of Quincy, pitching in to work the land with his neighbors as a matter of both principle and pleasure.) “Unlike so many aggressive male writers, who curdle into old curmudgeons with age, Berger grew softer,” Sperling writes. “Love took the place of sex as the site and origin of resistance: no longer revolution, but resistance.” I’d take some small issue with the idea that he soft-ened entirely, maybe as a way of agreeing that resistance remained important to Berger. He didn’t pick many fights, certainly not high-profile ones, and he worked steadily as a voice of endorsement and amplification for younger writers. But his objections were as fierce as ever, and well chosen. In “One Message Leading to Another,” published by the Massachusetts Review in 2011, Berger writes epigrammatically about the spreading familiarity of the prison condition.

The alarming pressure of high-grade working conditions has recently obliged the courts in Japan to recognize and define a new coroner’s category of “Death by Overwork.”

No other system, the gainfully employed are told, is feasible. There is no alternative. Take the elevator. The elevator is as small as a cell.

As he aged, he seemed like an English counterpart to James Baldwin, who wrote long-hand to encourage “shorter declarative sentences.” Both tended to the prophetic and blunt and each one modified a national archetype. Baldwin took the Christian pulpit from his abusive father and created a secular kind of preaching, a form of concentrated witness that refused to cool. Berger became the teacher he’d never found in “the ‘totally barbaric’ culture of the English boarding schools.” Berger knew Death with its cart would come, though it stayed in the wings and gave him more time than most. In the meantime, there was much to do—so much seeing, so much talking.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer living in the East Village.