GENIUS IS GENIUS in part because it defies narrative. Tall tales are spun to make sense of it, but a soul has never really been sold at the crossroads, and not every apple that falls on a head inspires cosmic revelations. For the couturier Charles James (1906–1978), his garments, the near-mythic exotica that he conjured, tell his story. “My seams are sentences,” he once wrote. “They all have meaning.” He referred to his designs as “theses,” expressions of ideas, arguments that he crafted with obsessive rigor and precision on behalf of beauty, glamour, sexuality. His gowns, suits, jackets, skirts, trousseaux, and trousers didn’t merely drape and fall, flatter and fit: They elevated a body, announcing it as a site for sculpting defiantly new forms. He preferred the verb shape to design, thinking the former evoked the personal, hands-on nature of couture, while the latter gave off the bland whiff of commercialism. James’s creations, like the man himself, were as outrageous and overblown as they were mesmerizing and astonishing, at times equally exquisite and insufferable, and always without care for the dulling opinions of others.

As one of twentieth-century fashion’s great innovators, James kept good company. Paul Poiret, his mentor, had liberated women from their corsets, allowing them to breathe. Colleague Coco Chanel’s pared-down femininity encouraged a sporting confidence in her clientele, while his friend Elsa Schiaparelli drew on surrealism to infuse her designs with sharp wit. Yet James was the most universally lauded among his peers and competitors. Mainbocher claimed that after James moved to New York from France to set up shop in 1939, “Paris—as a fashion center—was dead.” Cristóbal Balenciaga declared him “the greatest couturier in the world.” Virginia Woolf, a sometime contributor to British Vogue, declared him “a genius” for the way he cut and shaped a new hat for her right on top of her head.

For James, praise was fact, and no one crowed as loudly, or fought as ferociously, on behalf of his brilliance as he did. When Christian Dior showed his first collection in February 1947, launching what Harper’s Bazaar editor Carmel Snow would quickly crown the “New Look,” it was widely believed, and later admitted by Dior himself, that the French designer’s blooming silhouettes and haute sexuality owed a deep debt to James. If his voluminous ego expected to have such influence, and reveled in it too, it also demanded the acknowledgment thereof. “What people have been going mad for,” he said the following year in an interview published alongside illustrations that proved the primacy of his designs, “is nothing more than the summation of ten years of dressmaking development.” Hear that nothing more as a cheeky slap from a man who, in 1974, wrote a personal essay titled, with no detectable sarcasm, “A Portrait of a Genius by a Genius.” Still, in a single decade, the House of Dior produced twenty-two collections, transforming the designer into a household name the world over, while in his lifetime, James created only an estimated 250 to 300 designs, failed to expand his studio into a commercial empire, and spent his final years living in near squalor.

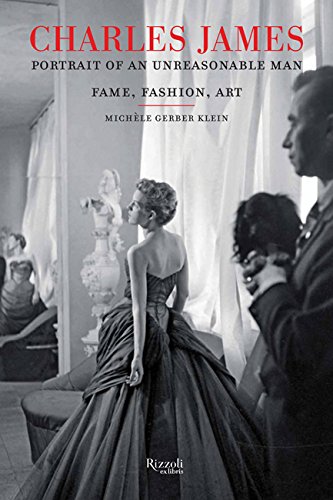

Two recent books weave new threads into James’s colorful story. Michèle Gerber Klein’s 2018 page-turner, Charles James: Portrait of an Unreasonable Man, follows the arc of the couturier’s life across his relationships with the women who were nearest to him: Schiaparelli, makeup mogul Elizabeth Arden, wealthy clients such as Millicent Rogers and Austine Hearst, and, finally, his wife, the midwestern heiress Nancy James (née Gregory). This year, in collaboration with designer/scholar Dorothea Mink, Homer Layne, James’s last assistant and the keeper of his archives until they were gifted to the Costume Institute in 2013, put together Charles James: The Couture Secrets of Shape, which in part realizes James’s own ambition to publish a book elucidating his practices so that younger generations may learn at his feet. Putting his notes, musings, and instructions together with patterns, illustrations, and photographs, The Couture Secrets of Shape presents a second portrait of the self-proclaimed “sartorial structural architect,” who seems more otherworldly than ever, though far less mysterious for what we now know of his life and work.

Charles Wilson Brega James was born the middle of three children to a wealthy, sophisticated American heiress and an aristocratic British captain. James was a glitteringly precocious boy—assertive, artistic, demanding—spoiled by his mother, scorned by his father. In 1920, he was sent to the Harrow School in London, where he befriended fellow student Cecil Beaton, a kindred spirit with whom he would remain in close cahoots until the two had a falling-out, as James so often did with his creative cohorts. While at school, he proudly declared himself homosexual. In 1923, disapproving of his adolescent son’s libertinism, his father ripped him from Harrow mid-term and, in a horrific turn, had his son raped by one of his officers, “so as to make a man of me,” as James later recounted.

Though exceptionally intelligent and artistic, James had little desire for higher education. Instead of attending university, he was sent to his mother’s hometown of Chicago, where he worked for Samuel Insull, a family friend, in the architectural department of Commonwealth Edison. There James learned the rudiments of design, though he didn’t stay long enough to learn them well. With a modest inheritance from his godfather, he opened up a millinery shop, first in town, then later in London, where he promoted himself by bedecking the heads, and then the bodies, of only the most graceful and connected society swans. Whatever James had in panache and vision, he sorely lacked in business acumen, a failing that would hamper his career, though he always handled his defeats with aplomb. The first time he declared bankruptcy, in 1931, not even a year after he’d set up his London shop, he celebrated by throwing a party for his nearest and dearest while selling off the last of his hats. Throughout his life he would shake off the humiliations of repossession, once by receiving creditors while lounging in bed, nude save for the furs he wrapped around himself, explaining to his unwanted guests that, regrettably, he had no money for pajamas.

James then hopped to Paris, where he cavorted with the likes of Poiret, Chanel, Schiaparelli, Jean Cocteau, Pavel Tchelitchew, and Salvador Dalí, breathing in the gale forces of the European avant-garde, casually studying the art of couture, and focusing his attention on developing what he would dub the “false profile,” by displacing the darts and seams of his garments in order to more accurately, engagingly, fit a body. His first triumph was the “Taxi” dress, 1931–32, which simply wrapped around a figure. It was, in the words of one of its earliest champions, Mary Hutchinson, “symmetrical, diabolical, and geometrically perfect.” Why “Taxi”? Because James wanted a dress that could easily be slipped off, then on again, in the back seat of a cab.

Although James had long identified as gay, he balked at the notion that libido should be hemmed in according to party lines: “You’re either sexual or you’re not,” he said, and while his clothes were largely envisioned for and commissioned by female clients, he was very happy to see them on any, and every, body. (In a photograph taken by Bill Cunningham in James’s studio in the ’60s, the great fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez is captured wearing James’s iconic eiderdown jacket, which Lopez reportedly wore to go dancing at clubs.) To James, one of the grand tasks of a couturier was to balance desire and delicacy, thereby charging a wearer’s aura with, in his words, the “erotical it.” He also understood that glamour is material only in part; the rest was the effect of a person’s character. Not everyone could pull off a Charles James, and he could be downright horrible to prospective clients who, in his estimation, had no business trying. One woman who came to visit his atelier was denounced by James as a “frump,” and was refused his services. Poet/translator Richard Howard recalled how artist Lee Krasner approached the designer to create outfits for her to wear to a British exhibition of her personal collection of Jackson Pollock paintings. James asked her how she wanted to present herself: “Do you expect to charm them? To astonish them? Do you want to take the room? I can make you look any way you want.” When Krasner told him that she wished to be invisible, he replied, “That, Mrs. Pollock, is one thing I cannot do for you.” In the end, Krasner opted to wear James, who rewired her desire to go unnoticed, instead making her look and feel, according to Howard, “invulnerable.”

The boldest of his designs were brazen articulations of the female form. In one 1948 creation, the skirt of a peach-hued silk faille ball gown was cut and draped to resemble parted labia, through which protrude clitoris-like swags of orange taffeta. The silhouette of his black-velvet and -satin “Lampshade Evening Dress” of 1955 appears like the hoop of a skirt that has fallen down around the ankles of its wearer; from other angles, its formfitting bodice and wildly domed hem look, ironically, like a penis and testicles. (Unfortunately, the names of his gowns were never as vivid as their shapes.) In 1948, James art-directed an advertisement for Modess sanitary napkins, working alongside his old school chum Beaton, who’d by then become a highly sought-after fashion photographer. In one of his most radical, empowering, and eccentric designs, James constructed a dress in silvery blue charmeuse, the skirt of which was decked with oversize rippling V shapes to recall a woman’s flow. “The spice of the campaign,” James explained, “is that every woman, at a ‘difficult time,’ can imagine herself a duchess.”

At the height of his career, James was dressing women of terrific wealth, power, and position—philanthropist and oil heiress Dominique de Menil, soprano Lily Pons, jewelry designer Elsa Peretti—but his studio was eternally on the brink of financial collapse. His unlawful business practices included a tax scheme he concocted for Millicent Rogers: He sold her a dress at an inflated price, which she then donated to a museum for a tax deduction. James thereafter gifted her a second dress. He was also known to borrow a garment back, claiming he wished to alter it, and then turn around and customize the same design for someone else. Hutchinson once noted that the duties of James’s clientele were “not so much ordering clothes as patronizing the arts.” His creations would sometimes be delivered at the last minute, or completely miss the occasion for which they had been commissioned. Pons legendarily held up an ocean liner until the dolman coat James designed for her arrived to meet her at the dock, while Krasner reportedly stopped off at his studio to be sewn into a suit on her way to the airport. Still other dresses took years to complete.

James’s delinquencies were blamed on his perfectionism; it was also rumored that he had become addicted to amphetamines. (Scholar Douglas Crimp, who briefly worked for James in the late 1960s, recalls the couturier dosing his assistant’s morning coffee with speed.) But James apprehended time and its demands differently. He had developed the concept of “metamorphology,” which insisted that endless designs could be wrought from a single garment by reshaping and rethinking its constituent parts. He followed his needle as one would a divining rod: patiently, determined. “I have sometimes spent twelve hours working on one seam; utterly entranced and not hungry or tired till finally it had as if of its own will found the precise place where it should be placed.” One of his most notorious achievements was the set-in sleeve, constructed to allow a woman to move her arms more freely without raising her jacket’s waistline or causing the shoulders to bunch at the collar. The project took him three years to research and develop, and cost nearly $20,000. The IRS would shut his business down for good in 1958.

Like their Svengali, some of James’s creations were ill-fated. “Inherent vice” is the phrase conservators use to label a garment that is self-destructing due to unstable elements or a flawed design. The couturier wasn’t thinking of longevity while he was realizing his visions; he was primarily interested in seeing his ideas take shape in the moment. Several of his pieces are now disintegrating and cannot be preserved. What’s more, the grandiosity of his garments could get them into trouble. His “Butterfly” gown of 1955 weighed eighteen pounds, with a paroxysm of tulle serving as its bustle. Wearers of his dresses were advised to carefully negotiate a room so that a hem wouldn’t be trampled on. (Invariably, it would be.) One client confessed that her dinner companion sat politely sideways at the table to make room for her dress. (There is, it must be said, eloquence, integrity, to designing a dress so that the world, at least at one party for one evening, would have to revolve around a woman.)

In the final decade of his life, James would rail against the “tyranny of amateurism,” scoffing at “the tacky, fag-hag-drag which has been passed off as fashion.” Though always self-aggrandizing, he was disdainful of the time younger designers wasted promoting themselves when they could have been mastering their craft. He taught a little, designed more, and tried, with help from Layne, to organize his archives. Thanks in largest part to Layne, The Couture Secrets of Shape proves how ahead—still ahead—James was of the times. Just as important as imparting and promoting his technical innovations is the book’s underlying lesson from the couturier: that an artist should stop at nothing to create what others believe is impossible. In her biography, Klein describes watching James in videotaped interviews from this time, noting that his hair was too black, like shoe polish, and that he had wrapped a rubber band around his head to give himself a face-lift. Although he lived surrounded by devotees comprising the chic and the gifted, he died on September 23, 1978, practically penniless. To see his life as a tragedy would be a failure of the imagination, of a certain ingenuity. A story, like beauty, is plastic, the product of perception. Or, as James once said, “art steps in where nature fails.”

Jennifer Krasinski is a senior editor of Artforum.