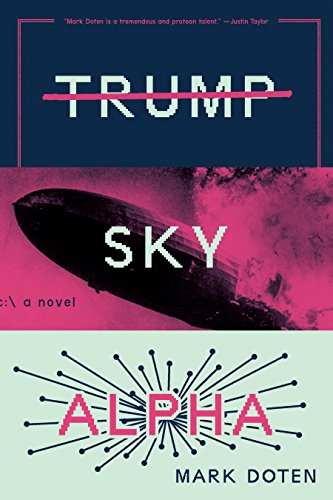

It begins with a nuclear holocaust unleashed by a former reality-TV star aboard an extravagantly self-branded zeppelin; it ends with a tech journalist running blindly into the graveyard once known as Prospect Park. Mark Doten’s Trump Sky Alpha is a bizarre chimera that cobbles together adventure story, torture porn, cautionary manifesto, sociopolitical satire, magazine interview, and metafiction.

I began reading the novel during a very strange week, although they’re all strange weeks. The president of the United States had invited the Clemson Tigers football team to dine at the White House in the midst of a prolonged government shutdown. As a result, he personally paid for a fast-food orgy, mugging over pizza, Filet-O-Fish sandwiches, and hundreds of hamburgers. “It’s all-American stuff,” he said, “but it’s good stuff . . . all of our favorite foods.”

Around the same time, an Instagram image of a plain, unadorned egg became the platform’s most liked post of all time. It was a triumph of sheer meaninglessness and virality. These two events harmonized unevenly, struggling to sing something about—what? The normalization of buffoonery, all the way to the big league? The ability of the internet to harness armies of strangers in the service of the good, the bad, the stupid?

Trump Sky Alpha pursues these tendencies to their absurd but not unbelievable extremes. A massive hack kneecaps the internet for around four days; during that total blackout, a number of nuclear events occur. The system comes back online, but only briefly. What follows is more carnage, an American president launching attacks from the command center of Trump Sky Alpha, his “Crystal Palace” in the air. An estimated 90 percent of the world’s population is exterminated. Survivors huddle together, policed by a virulently authoritarian government. Their eyes glow an unnerving gold; they’re allowed to open their curtains for only one hour each day.

Our protagonist, Rachel, is one of those survivors. A tech reporter, she’s holed up in Minneapolis’s “Twin Cities Metro Containment Zone.” Old habits die hard: She’s still hustling, pitching stories to the newly reformed New York Times Magazine, a shell of its former self, now headquartered in Modesto, California. Rachel wants to pursue an investigative piece that gets to the bottom of the hacks (she also wants to obtain permission to visit the Brooklyn graves of her wife and child). Her editor, Tom Galloway, wants a puffier look at “Internet humor at the end of the world.” They’re both constrained by the new Office of Communication Oversight, which preaches that “the truth is really whatever helps the system.”

Rachel is granted the rare ability to examine what remains of the internet, now housed in a secure, guarded facility. Her research leads her to a cult writer, Sebastian de Rosales, whose novel The Subversive provided the fictional model for the hack, perpetrated by a shadowy group known as the Aviary. It soon becomes clear that the government is using Rachel to find out the identity of the hackers. With this information, the government hopes to rewrite and regain control of the story.

Trump Sky Alpha succeeds more in the realm of the pre-, rather than the post-, apocalyptic. The opening section—in which we find a lonely, delusional Trump floating between Washington, New York, and Mar-a-Lago—is a thing of breathless, run-on beauty. (Trump returns later in the book, in the form of a transcription of his final monologue-from-blimp. Doten does an admirable job of replicating the president’s nonsense-patter, while realizing that a truly accurate rendering of his speech patterns would be unreadable.)

But the bulk of the novel is more like an autopsy, as Rachel struggles to diagnose the ills of a world that’s now mostly wreckage. Doten does his best to eke drama out of chapters that describe little more than someone sitting at a computer looking stuff up, which can at times reach comedic proportions: “I felt the mouse, its cheapness and lack of heft, the hollow feel of the plastic my body held.” Trump Sky Alpha is very much a part of the digital culture it satirizes. It may be a novel about the demise of the internet, but its digressions (on Linux, Jon Postel, BIND backdoors, zero-day attacks, the plot of The Matrix Reloaded, the history of the Philippines, and root authority tests) will have most readers rushing to Google. This heavily researched and referential approach can deliver polymathic thrills; other passages read like gussied-up Wikipedia entries.

Doten’s debut, The Infernal, was wilder than this: polyphonic, maddening, always on the verge of exploding its own seams. Ostensibly about the Iraq war, it ventriloquized its cast—Mark Zuckerberg, Roger Ailes, L. Paul Bremer, Osama bin Laden, and the author himself—to create a textual nightmare more experienced than read. That novel’s themes rose up, woozy and half-glimpsed, from a swamp of ecstatic language. Trump Sky Alpha, on the other hand, can seem straightforward and subdued, despite its experimental flourishes. The Infernal felt like an aggressive challenge, a dare to make sense of its garbled prophecies. Trump Sky Alpha is smaller—more like an extended essay with excursions into violence and intrigue, subplots involving child abuse, maniac billionaires, and trepanning.

The best parts of Doten’s book evince his talent for perverse, imaginative flights of fancy—the twenty-first century as a horrifying cartoon, one in which “destroyers were in charge, floor-shitters and fascists, failsons and large adult sons deconstructing the administrative state.” But Trump Sky Alpha’s momentum keeps getting stymied by digressions into hacker culture and noodling theories about how the rise of the internet paved the road to hell, some of which read like the world’s driest bumper stickers: “We remember the glorious subtweets of the deep state.”

Our contemporary America, this galling nadir, deserves something more unhinged, a wild yawp of anguish and disbelief rather than a tangled thesis. In the end, Doten leaves the simplest, sharpest verdict to Rachel: “This world was beautiful,” she observes. “Good but . . . it was really dumb.”

Scott Indrisek is a writer living in New York.