One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata.

Swanson was one of the highest-paid—and most dazzlingly famous—stars of the silent-film era, after signing with Cecil B. DeMille when she was only nineteen. If Mary Pickford was America’s Sweetheart, and Theda Bara its Goth Vamp Id, then Gloria Swanson was the Fashionable Cool Girl, gallivanting around Hollywood in peacock plumage and beaded tassels. She wore clothing from Paris and shoes from Italy and rarely appeared in public without being camera-ready, her saucer eyes rimmed with kohl. She was a proto-influencer, the kind of celebrity who could get thousands of women to buy a brand of soap simply by mentioning it in a sidebar in Photoplay.

She was also smart enough to know when her value had exceeded that of the men she was making money for. Somewhere, during her wandering Army-brat upbringing, Swanson had picked up an independent streak; she wanted to make the films she wanted to make, with financing she roped in herself. And she did, after joining United Artists, but it came with a liability: When her movies flopped, she was the one left holding the bag. With the exception of her one successful independent silent film, Sadie Thompson, the rest tanked. She tried to transition to talking pictures, and she proved that she could—The Trespasser, a drama in which Swanson played a poor woman who becomes entangled with two millionaires, was a hit—but by then her heart was no longer in it. She moved to New York City in the late 1930s, started a company that brought Jewish scientists to the United States during the war, hosted a series of political meetings out of an old theater, and shilled for beauty products and clothing lines. But mostly, she went out of style.

Flash forward to 1949, when Billy Wilder cast her in Sunset Boulevard as Norma Desmond, an aging screen siren and recluse who resides in a rococo mansion and has not made a film in decades. She lives in a fantasy world, one where she is still glamorous and relevant, ever teetering on the precipice of a comeback. Norma was a tricky role to cast—no one in town wanted to play a has-been. We now know how it ended—Swanson got an Oscar nomination, the film is no. 12 on the AFI’s 100 Greatest Movies list, and Norma is a camp icon for acerbic delusionals everywhere—but before the film debuted, nobody knew if it would work.

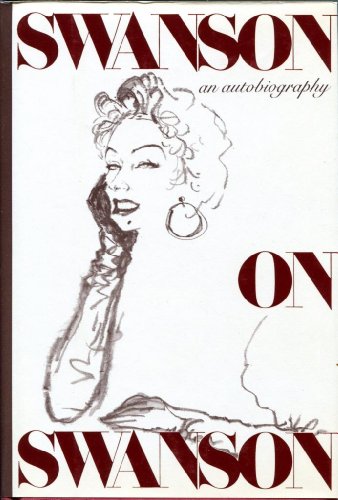

This is why Mayer’s dinner party was so crucial. The optics were good. Norma Desmond may have gone mad trying to claw her way back to her former glory, but Swanson still had favors left. Later that same night, Paramount screened the film for three hundred people on the studio lot. “These affairs are known for being morbidly restrained, devoid of the slightest overt reaction,” Swanson wrote in her best-selling memoir, Swanson on Swanson (1980). “But that night the whole audience stood up and cheered. . . . Barbara Stanwyck fell on her knees and kissed the hem of my skirt. I could read in all their eyes a single message of elation: If she can do it, why should we be terrified?”

It is impossible to know whether Stanwyck actually kissed Swanson’s dress that night. In all likelihood, it did not happen. (Stanwyck was not known for supplicating gestures, least of all toward other actresses.) But in Swanson’s mind, this was her Rudy moment, her epic flex. Personally, I live for this scene, which comes 484 pages into her autobiography, whether or not it is strictly true. Celebrity memoirs, at their best, read like opera: soaring, melodramatic, bathetic, false. But within this artifice there are moments of sublimity, full-throated arias that make you want to toss roses at the stage. Swanson’s memoir is jammed full of these moments. She was a woman who, throughout her life, had millions and millions of dollars, and champagne taste to match, and yet she makes you root for her as if she were a Dickensian changeling. You not only want to see her dripping in jewels, you also think the universe is misaligned if she is not. Swanson on Swanson, over the course of five hundred dense, looping pages, convinces you that Gloria Swanson was inevitable. She converts her life story into mythology, an ancient rime. And in doing so, she makes you want to turn the book over and start reading again. We know that Gloria May Josephine Swanson of Chicago, Illinois, grew up to be famous, marry six times, fall out of fame, and rise again, phoenixlike, for her second act. And yet we can’t get enough of hearing her explain exactly how she did it—and, more important, how it felt.

Every summer, when all I want to do is park myself in front of my air conditioner and read, I start to crave celebrity memoirs. I have a whole shelf of favorites: Shelley Winters’s Shelley: Also Known as Shirley, Anita Loos’s Kiss Hollywood Goodbye, Lauren Bacall’s By Myself and Then Some, Eartha Kitt’s I’m Still Here: Confessions of a Sex Kitten, Frank Langella’s Dropped Names. But I am not really discerning. My ideal activity on a summer day is to duck into the Strand and select a random memoir from the Film & Television section, then spend the rest of the day with it while melting ice on the back of my neck. These memoirs are, for the most part, full of lies. Most books are not fact-checked (still!), but stars get an extra pass; the fabulous tend to get away with being fabulists. The memoir is a dispatch from the highly constructed world of fame, a guide to understanding its languages and customs. It doesn’t need to be true. What it needs to be is consistent with the fantasy.

Swanson on Swanson was an immediate hit when it came out in 1980, but it was not Swanson’s idea. The concept for the book came from a man named Brian Degas, a mid-level screenwriter and, later, art gallerist, who looked around Hollywood in the late 1970s and realized it was missing a grande dame. Swanson had more or less disappeared from movie stardom again after Sunset Boulevard, choosing to focus on theater, television cameos, sculpting, and promoting her obsessive macrobiotic diet. Degas decided that he was the person to orchestrate another comeback and, in 1979, shopped the book to publishers without consulting her first. He delivered a forty-five-minute pitch about Swanson’s life to executives at Random House, saying that he had her participation in hand (he did not), and walked away with a contract.

In her younger years, when Swanson would turn down millions in order to preserve her autonomy, she might have been horrified. But at eighty years old, she recognized that she needed someone young to push her back into the spotlight. Swanson and Degas worked on the memoir in her Fifth Avenue apartment; I imagine what happened during those months was feverish and frenetic and full of long monologues we will never hear. All Swanson would say about the process was that Degas was a “very persuasive young man.”

What the two made, huddled together on the top floor of her building, was an American allegory. It divulges secrets—such as Swanson’s version of her long-running love affair with Joseph Kennedy—some of which must be true. But what it really exposes is the way Swanson felt about herself, and how we should read her. She opens the book with a scene in Passy, France, in 1925, when she has just married her third husband, Henri de La Falaise, a marquis. That morning, she writes (or “writes,” as Degas probably massaged her sentences), “lifted me to the very pinnacle of joy, but at the same time it led me to the edge of the most terrifying abyss that I had ever known.” This morning is her Mrs. Dalloway day, a single radiant moment that stands in for her entire life. She wants us to know she has experienced life as a series of colossal extremes. The length of the book—a door-stopper in red canvas—is just another example of this grandiosity. The book had to be long; and even then, it feels like it is struggling to contain her.

Reading star memoirs feels more like bingeing a reality series, only about twenty times more satisfying, as books tend to be soaked in details that the celebrity would never openly reveal on camera. It’s all performance, of course. No star has ever divulged a secret in her book that she was not willing to part with. But it’s communal performance. A book requires more hours of engagement than a film, more time spent ingesting and unraveling an aesthetic laid out for you by another person (maybe two people, if you count the ghostwriter). It’s less immediate than theater, but more intimate than the screen, which tosses up a scrim between the viewer and the viewed. At last, the diva invites us into her drawing room.

Rachel Syme lives in New York City. She writes the “On and Off the Avenue” fashion column for the New Yorker.