Last Witnesses was the second book by Svetlana Alexievich, originally published in 1985, the same year as her first, The Unwomanly Face of War. Both of them, like the three major works that followed—Zinky Boys (1990), Voices from Chernobyl (1997), and Secondhand Time (2013)—could be briefly and superficially described as oral histories. They indeed consist of testimony, recorded and transcribed, by witnesses to major events and periods in the history of the former Soviet Union.

Oral history is an important research tool, but it has not often been treated as literature. Although it obviously harks back to the oldest means of transmission, its publishing history is for the most part recent. Many of these published accounts consist of lengthy, unstructured, often repetitive monologues; they seldom make for good reading. In her books, Alexievich transforms the genre, turning it into literature through her editing and orchestration. That word is not idly chosen; there is a distinctly musical flow to the way she groups speakers and subjects. In Voices from Chernobyl, among multipage individual stories, she composes “choruses” of single-paragraph accounts by multiple people who underwent similar experiences. In Secondhand Time she assembles two chapters, both called “Snatches of Street Noise and Kitchen Conversations,” that replicate the experience of ambient talk and circulating notions; the speakers are distinguished from one another only by punctuation and sometimes speak only one line.

Alexievich’s impetus is of course more than literary. As a Belarusian born in Ukraine and writing in Russian—heir to the conjoined fates of the three countries—she has been on an urgent mission to collect memories before they disappear, to fill the immense gaps left by the constant rewriting of history by propaganda, both Soviet and post-Soviet. But a reliable account of objective history is not her quarry. As her 2015 Nobel citation says, she writes “a history of emotions, a history of the soul.” She does not provide recapitulations of events or much else by way of editorial matter (her foreign publishers sometimes do). If we do not already know the story in our bones, we can look it up. Her sequencing decisions often follow a broad chronological current that constantly doubles back on itself, but are otherwise undirected by factual demand. Her speakers echo one another’s experiences at points, although they sharply split off at others, and their personalities can emerge with startling clarity. As generally excellent as her translators have been, the reader deficient in Russian can only imagine the idioms, slang terms, bits of dialect, and particular rhythms that must color the original and bring those individual distinctions into even greater relief.

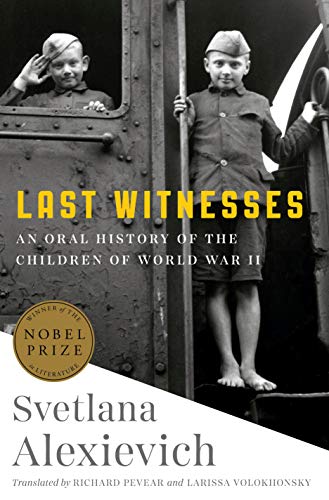

Her first two books cover what was known in the USSR as the Great Patriotic War, 1941–45. The Unwomanly Face of War gathered the memories of female military veterans of the war; Last Witnesses, which has just been translated into English, records children’s memories. Because the book was composed in the early ’80s, it of course collects the memories of older people who were children during the war, but those recollections are so deeply etched that they appear uncorrupted by passing time; in them their protagonists are forever children. Following Alexievich’s habit, the speakers are identified skeletally: name, age at the start of the war, current profession. Many of the speakers appear to be Belarusian—there are frequent references to Minsk and Vitebsk—which is to say that in 1941 they lived in the first line of attack by the Germans, coming over the border from Poland. Accounts of Alexievich’s methods note that she typically interviews three or four times the number of witnesses she ends up using, interviewing some subjects again and again and making them the thematic supports of the book. Here, 101 subjects are simply accorded a chapter apiece, and these run in a straight line, without topical subdivisions or breaks. The original Russian title translates as “A Hundred Unchildlike Lullabies.”

In 1941 these witnesses ranged in age from zero to fifteen; most lived in villages. There are more women than men. Some can remember the impossibly idyllic world before the war: “I remember songs. The women return from the fields singing songs. The sun is setting over the horizon, and from behind the hill, drawn-out singing reaches us.” But clear memories of the war can go back as far as age three, and they are nightmare images. A four-year-old boy remembers that chicks had just hatched when the bombing started. He was frantically trying to account for all the chicks, then started counting the bombs. “That’s how I learned to count.” In a column of refugees, a seven-year-old girl loses her mother, then loses her name. She can only remember the name a random unknown woman called her once, and does not learn her real name until twenty-five years later—and then doesn’t recognize it. Others don’t remember their parents’ faces or anything about them. They do remember being shot and left for dead, watching the murders of their mothers and fathers and siblings and grandparents, witnessing every kind of atrocity, walking long distances barefoot and barely clothed, starving for extended periods.

They all assimilated the logic of war, most of them quickly. Innocents were scarred into maturity overnight—just as, in the course of the book, two people’s hair is described as having turned white in a day. The witnesses are a select group, survivors of a vast carnage; they have come to terms with their experiences over forty years, and they know that they also speak for the dead. They are matter-of-fact in their accounts of terrible things—a nine-year-old girl remembers how after two families of partisans were hanged in the depths of winter, their frozen bodies “tinkled” as they swung in the wind; a twelve-year-old boy remembers using frozen German corpses as sleds. But they are hardly dispassionate. They remember and relive every emotion; the scenes they inhabited have inhabited them in turn.

The inhuman savagery of the Germans is a constant. The laughter of the soldiers as they carry out atrocities is nearly as monstrous as the crimes themselves. There are multiple references to the German belief that transfusions of the blood of children under five—preferably blond children—help soldiers recover quickly from their wounds; Russian children are bled to death for the cause. All of Belarus (along with Lithuania, Moldova, much of Ukraine, and parts of Latvia and Poland) fell within the Pale of Settlement, to which the Russian Empire exiled its Jewish population. Consequently, not a few Jewish people pass through these pages, sometimes as protagonists, sometimes as murder victims, sometimes as children concealed by others. Jewish children are identified by their hair, and yanked away by the Germans. The Holocaust does not loom especially large because, of course, it left fewer survivors, and many of those in the Soviet Union later emigrated.

There are multiple reminiscences concerning the finer points of starvation—eating wild plants, eating leather coats and whips, enduring unimaginable stretches of time with no food at all. A survivor of the siege of Leningrad enumerates the different grades of edible dirt, dug from the marketplace:

Dirt with sunflower oil spilled on it was particularly valued, or dirt soaked in burned jam. Those two were expensive. Our mama could only afford the cheapest dirt, which barrels of herring had stood on. The dirt only smelled of salt, but didn’t contain any salt. Only the smell of herring.

Decisions made regarding beloved animals are invariably wrenching. A nine-year-old boy stops soldiers about to shoot a cow with a broken leg so that he can first relieve its swollen udders: “The cow gratefully licked my shoulder. ‘Well.’ I stood up. ‘Now shoot.’ But I ran off so as not to see it.” A ten-year-old girl recalls her family and neighbors eating one another’s pets during the siege, since no one could bear to eat their own. She remembers as an authentic miracle a dog that followed her home at some point deep into the nine-hundred-day siege and saved her family from almost certain death. She has been asking the dog’s forgiveness ever since.

There are indeed occasional miracles—a twelve-year-old girl, separated from her mother and sister during the bombing of Minsk, knocks at a random door, and inside sees her mother’s wedding photo on the wall; she is in the house of a great-uncle she has never met. But the horror and misery seldom let up. The memories, often recounted in fastidious detail, are wildly sad one by one and emotionally overwhelming in aggregate. The book is guaranteed to leave any reader a sodden mess. If the most nightmarish recollections do not summon tears, those will be brought forth by the instances of kindness. “I want everybody to know the name of the woman who saved me,” says a Jewish girl. “Olympia Pozharitskaya, from the village of Genevichi, in the Volozhinsk district.” Somehow that specificity is the punctum.

It is extraordinary that any of these people could have survived, and that they went on to become plasterers and mechanical engineers and locksmiths and professors. But every account cites or implies the deaths of others, sometimes incredible numbers of them, and every account is the unveiling of an indelible scar. “I never married,” says a woman who was fourteen at the start of the war. “Never knew love. I was afraid: what if I give birth to a boy.” Because it was boys who shot her brother and father and forced her to smile as she and her mother buried them in the mud. But then a woman who was six at the time says, “What do I have left from the war? I don’t understand what strangers are, because my brother and I grew up among strangers. Strangers saved us. . . . All people are one’s own.”

Lucy Sante’s most recent book is The Other Paris (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015). She teaches at Bard College.