In retrospect, the show was destined to be a hit. My Favorite Murder. It’s all right there in the title: the chatty familiarity, the dark humor, the self-conscious voyeurism. The true-crime comedy podcast, started by Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark on a lark in January 2016, was fortuitously timed to coincide with the podcast and true-crime booms.

My Favorite Murder has become something more than just a popular program; it is a full-blown, blood-spattered phenomenon. These days, MFM’s twice-weekly episodes reliably rank among the most popular on iTunes, drawing 19 million monthly listeners. The podcast has spawned its own extensive and occasionally infight-y subculture. Fans self-identify as “murderinos” and schedule regular gatherings (Murderinos and Mimosas in Brooklyn; Murderino Meetup & Bingo in Kansas City; a “crafterino” stitch ’n’ bitch in Richmond, Virginia). They get tattoos of the show’s main catchphrase (“Stay sexy and don’t get murdered,” sometimes abbreviated as SSDGM). At the podcast’s live shows, they scream with such abandon that one friend-of-a-friend said she felt as though she understood what being at a Beatles concert must’ve been like. Coming to the podcast as a new listener three years into its run felt a little like being the new girl at brunch with a tight-knit group of friends. There are extensive murderino in-jokes and murderino argot; I realized that several phraselets my friends had been using (sweet baby angel!) had not, in fact, sprung from their own bright minds, but were actually popularized by Kilgariff and Hardstark.

The podcast’s primarily female listeners tend to describe their true-crime “addiction” in terms that other people reserve for sugar, or opiates. They have “an unhealthy obsession” with macabre stories. They crave and binge and overdose. The fact that white women, in particular, are fascinated by crime these days seems like a direct reaction to another dominant strain of contemporary femininity, one that mandates a serene, glowy wellness. Amid all those grain bowls and all that yoga, who wouldn’t want to indulge in some darkness, terror, and rage?

There’s nothing particularly groundbreaking in MFM’s content, which consists of revisiting crimes already metabolized by Forensic Files and Dateline. What is new about the podcast is its tone. From the beginning, Kilgariff and Hardstark made it clear that they weren’t interested in solemn memorializing or hard-hitting investigation; instead, they banter about abductions and dismemberments as if they’re gabbing over cocktails. The loose and digressive episodes typically run over an hour, during which Kilgariff and Hardstark toggle between self-deprecation, earnest cheerleading, and confessional honesty. They giggle and make fun of themselves for being bad at math; they talk about their therapists; they turn up the volume on their vocal fry in a self-conscious parody of what some people hate about women’s voices. When they do turn to murder, Kilgariff and Hardstark make no bones about reading straight from Wikipedia. They get enough facts wrong that many episodes start with a “corrections corner.” For fans, the hosts’ cheery refusal to do their homework is part of the show’s charm.

Kilgariff and Hardstark have repeatedly made the point that My Favorite Murder’s real subject is not violent crime but rather things like mental health and misogyny. For the show’s fans, murder is a metaphor for what it feels like to be panicked or vulnerable or out of control; hoarding facts about serial killers is a hedge against anxiety. Accordingly, the show has a powerful undercurrent of feminist self-help; one woman’s murder serves as an excuse to talk about another woman’s people-pleasing or self-doubt—habits that can get women killed, the hosts insist. (Another MFM catchphrase: “Fuck politeness.”) As I was writing this very paragraph, a friend walked into the coffee shop wearing an SSDGM hoodie and necklace. She told me that listening to the show has helped her stand up for herself in uncomfortable situations. “It’s like a form of #MeToo,” she told me. “Women have strong instincts and we’re taught not to trust them.”

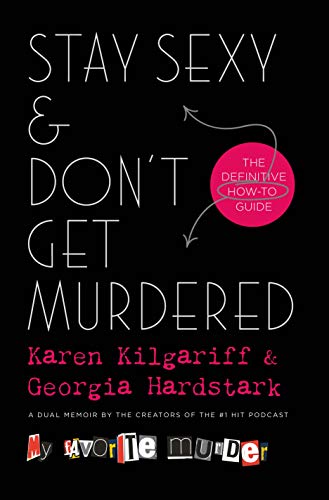

In the world of My Favorite Murder, confessing an “obsession” with true crime is an occasion for bonding, an entrée into a morbid sisterhood. So goes Kilgariff and Hardstark’s origin story, as described in their first book, Stay Sexy & Don’t Get Murdered: The Definitive How-To Guide (Forge, $25): They meet at a Halloween party, where they realize they’re both obsessed with the HBO show The Staircase. After talking for “hours and hours” at a lunch date, they decide to start a podcast.

The book takes a form—part memoir, part self-help manual, with the writer inhabiting the role of your warm but no-nonsense BFF—that’s been popular of late (see, for instance, Girl, Wash Your Face). Kilgariff and Hardstark offer up self-parodying stories and hard-won wisdom, seasoned with enough straight talk to ward off accusations of sentimentality. There are extended set pieces about childhood antics, enumerated regrets from their teens and twenties, and epiphanies from therapy. The memoir portions of the book offer a zippy tour through the hosts’ various substance issues, food issues, subpar boyfriends, minimum-wage jobs, and distracted mothers. One repeated theme is how different things were back in the mid-’70s to the mid-’90s, when Kilgariff and Hardstark were coming of age: “I think kids are way too sheltered these days . . . that said, there’s some shit I saw as a kid, both fictional and non-, that greatly contributed to my pretty significant anxiety disorder,” Hardstark writes. “So yeah, maybe don’t let your kid watch Robocop at eight years old (I’m side-eyeing you, Mom).”

The advice largely consists of reiterating key points made on the show: Have people in your life who will call you on your bullshit; “self-sufficiency is your first form of self-defense.” Like the podcast, the book is casual and episodic, written in a style that heavily favors all-caps emphasis and exuberant punctuation: “Ugh. People who claim to have all the answers NEVER have ANY answers”; “Who the hell listens to bagpipe music?? With kids???” (I suspect that Stay Sexy & Don’t Get Murdered is one of those rare books that is more appealing to listen to than to read.)

Kilgariff and Hardstark allude to a few victims of the kinds of murders they and their audiences tend to gravitate toward—that is, white women and girls killed by strangers from that same mid-’70s to mid-’90s period. But one striking thing about Stay Sexy & Don’t Get Murdered is how little murder there is in it. Perhaps that’s because mixing true crime and advice can get awkward. Kilgariff writes about learning this lesson early in the show’s history: “We thought if we identified [a murder victim’s] ‘big mistake’ and then pointed it out, a preventative measure could be taken. . . . The solutions were practical, organic, and most importantly, effective: use the buddy system, get a large dog, generally mistrust all strangers, stay out of the forest.” But to some fans, this framing sounded like blaming the victim. Kilgariff and Hardstark listened to their listeners’ concerns and modulated their language accordingly. For similar reasons, they stopped saying “prostitute” and began using “sex worker” instead.

Even with the more sensitive terminology, though, the show’s approach is limited. By framing murder stories around self-empowerment and personal choice—in claiming that “Being ‘Polite’ Often Gets Women Killed,” as a BuzzFeed headline about the show proclaimed—MFM starts to seem like a macabre version of lean-in feminism. The show delves into the tawdry details and pop psychology of particular crimes, implying that murder is a function of aberrant, atomized individuals—evil monsters, as MFM’s hosts are quick to say—who prey on “sweet baby angels.” This closes off angles of discussion that might provide a broader cultural critique. True crime could be a springboard to talk about housing insecurity or discrimination against sex workers; it rarely is. You could argue, of course, that those topics are too serious for a show that’s explicitly comedic. But then again, isn’t murder?

Kilgariff and Hardstark sometimes offer critiques of mainstream true crime—namely, its judgment of women’s sexuality and its dismissal of women’s fears. Too often, though, they replicate the genre’s biases and blind spots, its implicit assumptions that some lives matter more than others. An MFM binge may leave listeners with mistaken beliefs about who’s really vulnerable. The podcast favors stories in which a male perpetrator kills a female victim, even though these crimes make up only a quarter of all homicides; in reality, most murder victims are young black men. This distorted sense of risk is exacerbated by the show’s rehashing of crimes from decades ago. The murder rate now is half what it was then, though you wouldn’t know that from MFM. On the podcast, Kilgariff and Hardstark have occasionally wrestled with the true-crime convention of focusing on dead white women. Their book, though, mentions race only once, and in passing. This is a fraught omission, particularly considering how stories of imperiled white women have long been mobilized to serve politically repressive ends.

I can imagine the murderinos coming for me now: I’m taking this all too seriously, piling too much responsibility on two nice ladies who just want to make some jokes. It’s clear that MFM provides some vital nutrient that many women are craving nowadays. After these past few years, no one could be blamed for feeling like the world is a precarious, unsafe place; perhaps banter about murder is an adaptive response to our extreme times. But a casual approach to stories of violent death becomes unsettling when it brushes up against the realities of violent death: In the three years the podcast has existed, at least two avid listeners have been murdered—one by her roommate, another by her husband—a subject that isn’t addressed in the book.

Ultimately, murder is only “fun” when regarded from a certain distance. “Baltimore has a higher murder rate than Chicago,” Kilgariff said at a recent live show in Baltimore. A portion of the audience erupted in boisterous hoots and applause. Kilgariff started over—this clearly wasn’t supposed to be a celebratory line—but the women in the audience cheered again, undaunted.

Rachel Monroe’s Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime and Obsession will be published by Scribner in August.