The gold- and silver-colored crucifix that hung opposite my childhood bed was only one of many that adorned the walls of my home, my school, and, of course, the church I attended. On early-summer mornings the bright, filigreed metal caught the rays that leaked around a too-narrow window shade and the dying Christ glowed as if electrified. At age eight I understood the principle of reflected light but didn’t yet grasp the concept of an afterimage—the result of photoreceptors retaining an impression after the eye is closed or upon looking away from the object. After waking one morning, I allowed my gaze to linger awhile on the shiny thing, and when I rose I found I couldn’t rid my vision of its specter: A cross hovered just in front of me as I stood at the toilet, and it grew even more vibrant when I closed my eyes. Years of parochial school and a diet of religious movies about Bernadette of Lourdes and the children of Fátima had primed an acceptance of the miraculous. So, try as I might to blink away the apparition, I began to believe I’d been chosen for a visitation from the Lord.

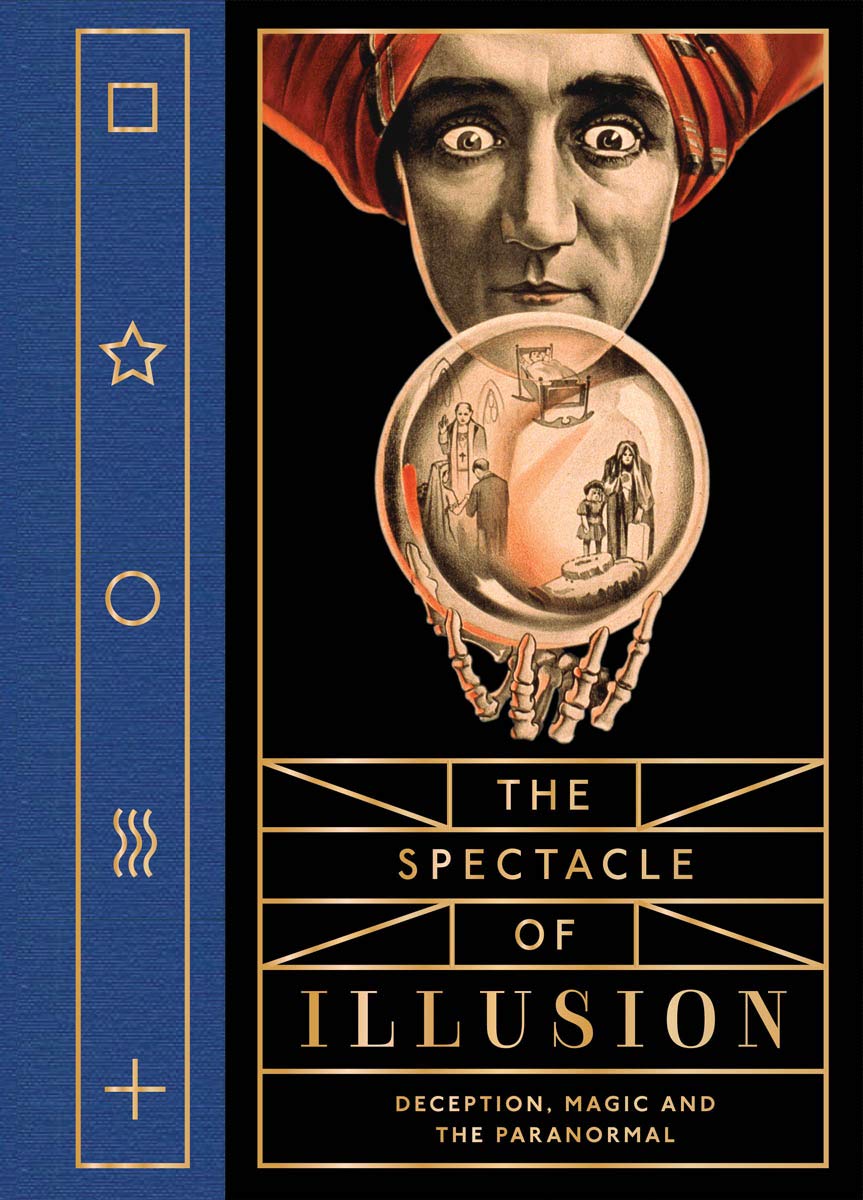

That this spark of faith flickered for even a few minutes before I dismissed the idea (and turned to training an errant cowlick in the mirror) always struck me, from my adult vantage, as a wondrous thing. While, in subsequent years, spirituality, the supernatural, and magic have failed to gain much purchase with me, that morning I did thrill to a sliver of the otherworldly. The prospect of departing from dreary material reality for airier, more malleable territories animates most spiritual beliefs and, of course, most art. Magic is one entertainment designed to ignite wonder and possibility—a deck of cards suddenly made all clubs speaks to the same human need for joy and transcendence as an appearance of the True Cross above the commode. For The Spectacle of Illusion, Matthew L. Tompkins has compiled a trove of posters, photos, and illustrations from magical, psychic, and spiritualist practices over the past two centuries that evidences both the strong lure of enchantments and the meticulousness of their deceptions. The assemblage also proves intriguing as it unintentionally suggests a kinship between some portion of twentieth-century art and magic and the occult. Their imagistic vocabulary, one that performs the fluidity of bodies and the transformational nature of objects, finds parallel expression in the work of artists from Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning to Louise Bourgeois and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

The twined phenomena of spiritualism and mesmerism thrived during a period—the mid-to-late nineteenth century—when photography might have been deployed to challenge practitioners’ claims of mind reading and communication with the dead. But almost immediately, magicians and fraudsters put the technology to use to promote and validate their shady arts.

While the earnest theatricality that characterizes depictions of séances and hypnotized subjects now registers as camp, nineteenth-century viewers were likely less jaded about the portrayal of strong emotion, as well as the presumed authenticity of photographic images. A pair of photos from 1866 portray German magician Jacoby-Harms contemplating floating objects—a violin, tambourine, and drum, in one; a skull, in the other. In both, a disembodied hand gestures reassuringly. The conjurer has fallen to the floor in response to the hovering instruments (and their accompanying sheet-covered ghost); in contrast, he regards the skull matter-of-factly. These images doubtless served to excite as well as soothe: The spirit world might not be subject to known physical laws, but its emissaries meant no harm. In the nineteenth century, there would have been few reference points for such gravity-less domains, yet a few decades later they would become common visual tropes in, say, the work of Chagall and Dalí, as evocations of intense inwardness and dreams, both elements on a continuum with the mystical.

By trafficking in a common longing for connection to something larger than the self (and fear of mortality), illusionists probed the psychological undercurrents of their audiences—and those audiences, in turn, responded to the proposition that they possessed a deeper inner life than they were aware of, one capable of communion with a shared yet unseen realm. No doubt this is why Freud employed hypnosis early in his career as a means of accessing the unconscious. Had he discovered the all too tangible evidence of psychosexual stages demonstrated by a photo from the turn-of-the-century manual Practical Lessons in Hypnotism, he might not have abandoned the practice. In this image, a hypnotist stands behind a pair of beguiled children, a boy reclining in a girl’s lap, and places his hands as if in benediction over their heads. The caption reads, “The young gentleman believes himself to be once again a nursing infant while the young lady thinks she is a nurse in a foundling asylum.” Hypnotists claimed to offer previously unimagined views of primal states, and manuals promised “methods for curing your own ailments without either drugs, doctors, expense or exposure,” as well as a means of transferring a healing “magnetic fluid” from practitioner to patient. One photo, of a man unbothered by a needle piercing his tongue, testifies to the power to transcend pain itself.

One of the odder phenomena documented in The Spectacle of Illusion is the supposed “ejaculation” of ectoplasm—a fluidlike substance that hardened as it poured from the nose or mouth of a medium during a séance. Photos of these emanations were posited as proof of spiritual energies acting on the body. Mediums were typically shown unconscious, head thrown back and face covered in a ragged mass of cheesecloth or gauze that they had hidden on their person before the ceremony. Harry Price, a paranormal investigator, discovered that one famous medium active in the 1930s and ’40s, Helen Duncan, was able to ingest the cloth before the séance and regurgitate it, to dramatic effect. Duncan also concealed the material in a “variety of her bodily orifices.” One photo shows a voluminous rope of ectoplasm flowing from her mouth to the floor, which leads one to wonder about the capacity of those hiding spots. In many images of mediums—most of whom were women—there is a strong sexual implication; the unruly body is revealed as being subject to forces greater than its ability to control. Such imagery could never have been cast as explicitly erotic, yet to audiences then the intimation would have been undeniable, though disguised as a quasi-religious manifestation. In a series of photos taken of medium Mina Crandon, this sexual undertone advances to what could be construed as a representation of childbirth. Crandon reclines motionless as a disembodied hand appears to emerge from between her legs (retrieved by her husband, who was always at her side during this demonstration). The scene’s provocativeness remains undiminished by the likelihood that the “hand” was actually a lump of animal liver. However fraudulent these performances, they nevertheless show the female body as vulnerable and disruptively corporeal in ways that anticipate the work of Carolee Schneemann (think Interior Scroll), Marina Abramović, and Ana Mendieta.

Throughout this volume, bodies in thrall to magicians or the supernatural are often asleep or almost comically passive, given the dire circumstances. In a full-color German poster from 1923, the tuxedo-clad magician holds a vividly serrated saw while his assistant, a woman wearing only a slip, lies peacefully on a table. In the smaller inset image, the saw cuts deep into her stomach, yet she retains an implausible equanimity. A poster advertising the magician Harry Kellar’s most famous trick depicts the levitation of a supine “Hindu princess” who also appears to be lost among blissful dreams. The psychosexual import of these images—male mastery over acquiescent women—is not dissimilar from the power dynamic between artist and model, in which the artist has complete control over the model’s representation. The radical reconfiguration of female figures by painters like Picasso and de Kooning might be compared to the effects achieved by the popular “Zig-Zag Girl” illusion. A “lovely assistant” is placed in a vertical cabinet with only her head and left foot visible; the middle of the cabinet—her torso, according to the schematic body painted on the exterior—is pulled away to reveal a gap. Where has everything but her head, shoulders, and legs gone? Variations on the trick feature sections of the cabinet (and the assistant’s body) being rearranged like Legos. The plasticity of the body, of the self, isn’t restricted to women: Posters show Kellar decapitating himself—his halo-ringed head rising from his starched collar. And stills from an 1898 Georges Méliès short film titled “The Four Troublesome Heads” make use of trick photography to show the director performing the same self-separation three times and then placing the heads on a table to sing along as he strums a guitar.

The French filmmaker’s humorous nonchalance contrasts markedly with the serious countenances worn by most of the supernatural world’s ministers and acolytes. The mediums and mesmerists, magicians and crystal-gazers all appear burdened by their visions and powers. And perhaps they should be. The desire to believe in something more than what’s visible and tangible is undeniably tenacious, and these would-be wizards and conjurers are teasing that desire as much as any artist or cleric. A trick that allows the dead to speak—or a painting like Tanning’s Fish Out of Water, in which a woman communes with a trout—entices us with the possible comprehension of the unknown. That cross that hung before my eyes can be readily explained; less so the excitement I felt when I believed I was seeing what shouldn’t be seen.

Albert Mobilio’s most recent book is Games and Stunts (Black Square Editions, 2017).