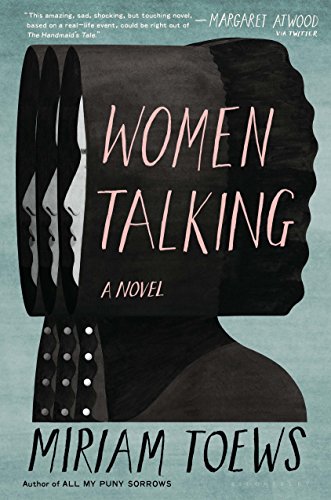

What we talk about when we talk about women talking: Gossip. Secrets. Men. Sex. Babies. Broken hearts. First dates. Messy divorces. The Bechdel Test. Men again. Still. Always?

In Miriam Toews’s new novel, Women Talking, the women are talking about men. Specifically, they are talking about the men who have repeatedly drugged and raped them in their remote Mennonite colony, knocking them out with an animal tranquilizer in the middle of the night before violating them in their own bedrooms. After years of being told that they were suffering from hysterical delusions, or else being punished by demons for their sins of impurity, the women “came to understand that they were collectively dreaming one dream, and that it wasn’t a dream at all.” Women Talking is based on actual rapes that occurred on a Mennonite settlement in Bolivia between 2005 and 2009. But the book is less an indignant manifesto about sexual trauma, or a speculative celebration of female empowerment, than it is a confession of violence as something stitched into the fabric of every community, and an exploration of what it means to claim communal thought—even disagreement itself—as an inalienable human right.

The book opens with three curious black-and-white images that look like miniature woodcuts: The first features puffy clouds hanging over a field, the second a man and woman thrusting knives at each other, and the third a horse gazing back over its shoulder. Six pages into the novel, we realize that this trio of images is a reproduction of the secret ballot distributed to the women of the colony, all illiterate, the day before the novel begins. With these ballots, the women could vote on how to respond to the rapes: They could do nothing (field with clouds), stay and fight (couple with knives), or pick up and leave (horse with backward glance).

Women Talking tells the story of eight women who voted against doing nothing. Over the course of two days, they conduct a secret conversation (hence the title) in the barn loft of a senile colony elder named Earnest. In its compression, the novel tracks a single discussion whose stakes couldn’t be higher: These women are debating not only their future—should they pack up their children and leave for good?—but the nature of evil itself, and the possibilities of justice.

To be blunt, I was worried that I’d find this book insufferable. I feared its premise would conscript its characters into the dull work of spouting rigid ideas about authority, gender inequality, or toxic masculinity. Nothing flattens consciousness like the obligations of color-by-numbers philosophical debate. It reduces characters to lifeless abstractions—what a person might be, or what a person would say—in service of a theory of personhood or an argument about justice, abandoning the messy vitality of how we actually are.

Thankfully, Women Talking crackles with the energy of consciousness on every page. Its attention is tender and funny, its characters utterly distinct and alive: There is Greta Loewen, a grandmother who wears a set of false teeth because her attackers knocked out her real ones when they raped her in the night, and who remains passionately committed to the fate of her elderly horses, Ruth and Cheryl. Her daughter Mejal is “a friendly chainsmoker with two yellow fingertips and . . . a secret life.” Mejal’s good friend Salome Friesen walked twelve miles to get her three-year-old daughter antibiotics after the girl contracted an STD, and then—in her fury at her daughter’s violation—attacked the alleged perpetrators with a scythe. Salome’s sister Ona, the group’s unassuming intellectual leader, is a single woman pregnant from her own attack, who frequently interrupts her own eloquent meditations on forgiveness to vomit in a nearby bucket.

These bursts of nausea are one of many examples of Toews’s attention to how profundity always sits alongside the mundane work of living in a particular body, in a particular place and time, in a particular community—whether that daily work involves tilling fields or paying rent, holding a crying child on your lap or carrying the unborn child of your rapist, pausing mid-sentence when morning sickness overtakes you. The novel is deeply aware of how this simultaneity—the weighty sitting shoulder to shoulder with the daily—is especially inescapable for women. It’s the women who have to take care of other people and one another even as they plot their revolution: Mariche, Greta’s daughter, dislodges a cherry pit from her young son’s nose by sucking it out like snake venom; Mejal takes senile Earnest to give him a hot bath, full of fresh mint leaves from the field, when he discovers the women in his barn; Ona lays a wet washcloth across her agitated mother’s forehead and helps her lift her swollen feet down the barn ladder. Even these women talking depends upon another woman’s labor. The whole time they are conversing in the barn, a woman named Nettie is watching their children. Nettie remains mute by day but falls into fits of screaming by night, haunted by losing a premature son conceived by rape, born “so tiny he fit into her shoe” and dead a few hours later. After he died, she smeared his blood across the walls of her bedroom and stopped speaking to anyone but children.

Toews doesn’t just allow the trivial to live alongside the weighty, she insists on it. These pages are full of pranks and crushes and grudges and tiny strokes of tenderness; women sweating and breathing and scratching their insect-bitten ankles, remarking on the way trauma has affected their children’s toilet training, sharing quick glances of understanding and boredom, flashes of irritation and intuition. By refusing to segregate the mundane from the consequential, Toews implicitly argues that what we call trivial often isn’t trivial at all—that just as much truth lives inside those small moments of care and grace as in our grand philosophizing about authority and justice—and allows her characters to come to life as more than helpless victims or walking thesis statements.

Women Talking resists false binaries at every turn. Profundity and banality are entangled. People are consistently inconsistent in their desires. Evil can’t be neatly jailed, or easily fled. The villains in this story are also family. The men who have terrorized these women are also the ones they have built their lives with. As Ona puts it, “The people we love are people we also fear.” In other words, the call is coming from inside the house. Even this public conversation is happening in a private barn.

Just as violence follows no reliable arithmetic in its origins, trauma follows no predictable blueprint for the damage it will leave behind. You might try to kill a man. You might try to kill yourself. You might speak out. You might stop speaking entirely. These women embody a set of lively alternatives to the literary archetypes of the Sad Woman, passive and picturesque in her woundedness, and the Angry Woman, fierce and feral in her rage. These women are something else: They are practical. They haven’t had the luxury of devoting their lives to sadness. They’ve been too busy getting things done. During a conversation about the implications of leaving behind their adult husbands and brothers and sons, some start crying, and others offer comfort, until one elderly matriarch gently interrupts the proceedings to say: “Let’s talk about our sadness after we have nailed down our plan.”

Women Talking is narrated by a man named August Epp, an outsider in the colony whose backstory we catch in glimpses between swaths of transcription: His parents were excommunicated when he was twelve and he grew up in England, where he eventually joined an anarchist collective and spent time in prison for stealing a horse. Now he’s once again living in the colony, but his position is precarious. The men regard him with suspicion. These women have asked him to transcribe their conversation because they are not literate themselves.

What does it mean to have a man narrating a novel about women talking? On the surface, it inverts a familiar power dynamic. The women have the ideas, while the man is just their secretary. His hopeless crush on Ona Friesen is woven like a glimmering thread through the whole book, making him foolish and self-conscious, clumsy with longing. He measures every one of her glances for clues about whether she loves him back; this question is one of the simmering, tenderly compelling tensions of the book.

Like a character in the comedic subplot of a Shakespearean tragedy, August plays the part of bumbling lovelorn scribe. But he cannot shake the privileges embedded in his gender, and his narration forces us to recognize that structures of inequality shape even the conversations that are rebelling against them. August is only able to transcribe this conversation—at one point, using an old cheese wrapper—because he has profited from the same patriarchal inequalities that have left the women illiterate. His presence as a male narrator calls us back from the barn dream of total female autonomy, just as the fact that this novel is based on real-life events calls us back from the dream of fiction itself—not only the fantasy that these characters will end up “OK,” whatever that would mean, but the deeper fantasy that even if things turned out well for these fictional characters, it would somehow solve or even mitigate the violence upon which their plight was based.

The core struggle of the book, of course, is precisely this wrestling with the question of what can possibly ameliorate the effects of violence. How much can conversation solve? How much can fleeing remedy? Where does hope live?

At one point, August interrupts the women to suggest that hope might dwell in the very fact of their persistence. He tells them about a “mysterious river that scientists believe can sustain life in the bottom part of the Black Sea,” because fossils show imprints of soft tissue suggesting that—inexplicably, against all odds—these dark anoxic waters have not killed everything. Though August offers this metaphor with earnest intentions, wanting to “somehow convey that life and the preservation of life is a possibility even when circumstances appear to be hopeless,” the women range from insulted to skeptical in their reactions. Mariche wants to know if August is comparing the women to the “lower layers” of water, suggesting that they should stay despite the life-draining pressure of the men. Ona wants to know, “What is soft tissue, exactly?” She wonders: Are the women the soft tissue? Salome disagrees with her: The women are the deep waters!

As with so much of the novel, the exchange works on several levels at once: The content of the metaphor explores the possibility of survival under difficult conditions, but it’s the nature of the discussion—the back-and-forth, the disagreement, the misunderstanding and the desire to be understood—that illuminates what this survival might look like in practice. August seeks consolation in the resonance of comparison, but it’s the way his metaphor doesn’t land that illustrates the unwieldy innards of communal thought. The truth of the metaphor doesn’t dwell in its content so much as in the messy arc of its response, the awkward confusion about tenor and vehicle: Are we the soft parts? The dark water? The river? The fossils? The oxygen itself? The metaphor itself is simple in the same way I feared the novel would be disappointing—it’s a color-by-numbers allegory of survival—but the churn and tug of the debate it inspires becomes something far more compelling. The right to dispute the river, and to argue about its meaning—these rights are the oxygen and current, the elements that make survival possible.

The scene about the secret river is also quite funny—which is part of its purpose, too. This is a funny book. But its humor always takes us deeper into consciousness, into the nuances of how people ache and want, rather than deflecting us away from the white-hot core of human hurt and yearning that flows like a secret river—or not!—beneath the novel’s fluid conversational layers. Toews grants emotion room to be contradictory and double-edged: Not just sadness but the need to make a plan. Not just sadness but the need to make a joke. If Toews is asking how we can respond to trauma, she is asking not just about the grand philosophical business of vengeance, but also about the granular questions of what it means to bear sadness alongside the need to make dinner, the need to get a cherry pit out of a little boy’s nose, the need to make sure there’s enough hard bread in the wagons for a long journey on the road.

While the horrors in Women Talking are drawn straight from the world, its hope is entirely imagined. On the Manitoba Colony in Bolivia, the women were not only denied the right to talk to therapists, there was no community-wide conversation about the rapes. So Toews’s choice to frame the entire novel around a conversation gives its characters precisely what their real-life counterparts were denied. And the novel’s closing pages find these women setting off into an unknown future—possibly about to run into the colony’s men returning from town, possibly walking straight into a wildfire, possibly headed to freedom. Even this unstable horizon of possibility is much more than what awaited the women on the Manitoba Colony; as Jean Friedman-Rudovsky reported for Vice in 2013, the rapes were still happening long after the original perpetrators were imprisoned. This novel knows that truth: Violence is something more systemic than a few rapists; more like a wildfire than a small burn contained to a few toxic bodies you can lock away for good.

In a brief preface, Toews describes her novel as “a reaction through fiction to these true-life events, and an act of female imagination.” But it’s an act of imagination that also forces us to confront the limits of imagination, and of conversation itself. In the ongoing aftermath of the #MeToo movement, it’s become clear that “speaking out” is both necessary and insufficient. Gendered violence and abiding inequality are too deeply baked into our power structures and our social order. The ones we love are also the ones we fear. Women talking helps, but it’s not enough. At the end of this book, I rooted for Ona and Mariche and Salome with every bone in my body—rooted for them to make it to a new future, to walk away from the fire, or through it—but it was hard to know what, exactly, I was rooting for if I followed these ideas back into reality. What would it mean to get on the back of a horse and leave the world behind?

The absence of a takeaway is not a failure of this novel, but one of the core truths it recognizes. It’s not an allegory with a moral. It’s hard and messy and ultimately unresolved. Before the women set off, Agata, Ona’s mother, says it’s pointless to speculate about the future: “Let’s not waste time by dwelling on the unknown,” she says. Ona replies, “But that’s what thinking is.”

In the final few pages, August writes a list of “good things” because one of the grandmothers has requested it. This list includes stars, pails, birth, beams, flies, manure, wind. Even futility. If a solution is impossible, then the making of this list in the face of that impossibility might be closer to the point—the desire to leave behind an artifact of reckoning. The catalogue offers a surge of possibility in its luminous particulars, an affirmation of the world alongside an acknowledgment of its trauma. But I also detected a clear-eyed sense of impotence lurking in its margins. If the list had been allowed to occupy the very last pages of the novel, it might have felt precious or deluded: a false note of sentimental hope, as if systemic gendered violence could be solved by warm dusk light on the fields, or the sudden glow of a firefly. But the novel actually closes with August standing watch over two teenage boys who have been knocked unconscious with the same tranquilizer used on the women for years—to keep these boys quiet, so they won’t give away that the women have fled. We land on this uneasy plot twist—violence used to fight violence—rather than the gorgeous list of affirmations that precedes it.

I felt implicated by loving the list as much as I did. I wanted to stay inside it forever, surrounded by the smells of fresh bread and clean laundry, consoled by the primal bond between a mother and her unborn child. “I already love this child more than anything,” Ona says of hers, but also, a few pages later, “I don’t believe in the security that you say love brings.” August’s list insists upon “good things,” but these good things don’t dissolve anyone’s pain. They just sit alongside it. And the brilliance of the novel is that it lets them: Stars. Birth. Wind. Women. It holds the persistence of their grace while refusing to make false promises about the redemption or vindication waiting for them beyond its final page.

Leslie Jamison’s Make It Scream, Make It Burn will be published in September by Little, Brown.