Peter McGough met David McDermott in a Manhattan theater at the end of the 1970s and the rest is history.

McDermott was famous downtown for having odd manners and donning outdated formalwear, including detachable collars, cummerbunds, top hats, and tails. A Fashion Institute of Technology dropout, McGough wasn’t famous yet; he was employed selling drink tickets at Danceteria, wearing less memorable getups. A courtship developed as David kept Peter company during early-morning club hours just before sunrise.

They eventually joined artistic forces, forming the alliance still known today as McDermott & McGough. After their early years together, spent in bohemian poverty, their art began selling extremely well. Over the course of their wild ascent to success in the art world, which took them on QE2 rides around the globe through the postmodern 1980s and ’90s, their collaborative output took shape as a proliferation of paintings, drawings, photographs, and interiors. They also thought of their everyday lives as another kind of art: In what they called “time experiments,” they would carry on as if in a dream of the premodern past, a place without electricity, telecommunication, air travel, convenience plumbing, or refrigeration. The eccentric duo was lauded, feted, misunderstood, and eventually derided. They were paid handsomely and spent lavishly, until they lost it all.

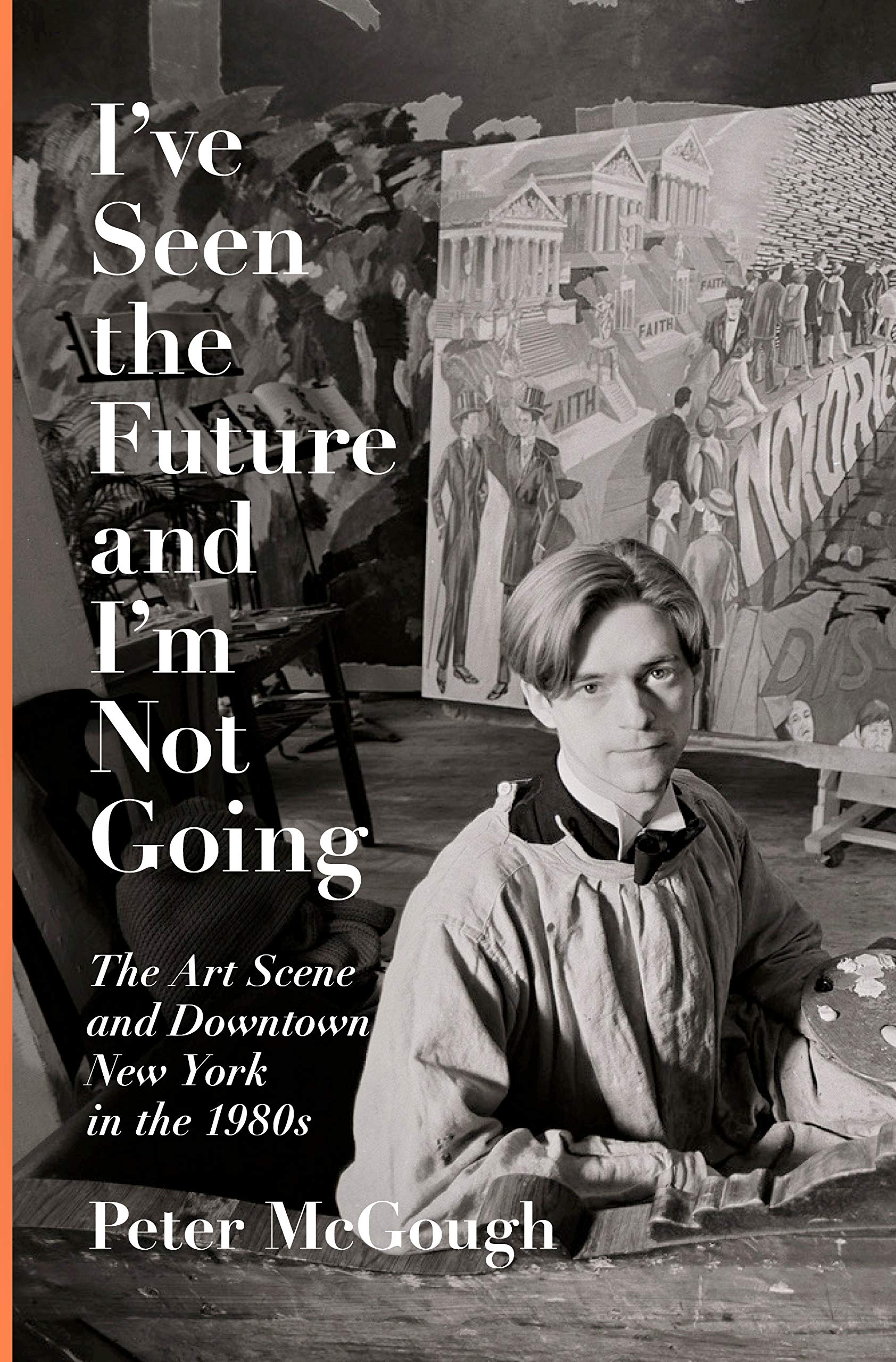

In his new memoir, I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going, McGough provides a warm and witty account of his exploits with McDermott, recalling a conspiratorial atmosphere of profligate recklessness:

One day David saw a 1930s convertible coupe for sale in the paper. Calling from Massimo’s gallery phone . . . he made an appointment with the seller on Long Island. A day or two later we were on the train.

“Where are we going to get the money to buy it, David?”

“Oh, will you please stop! It’s only a few thousand, and we can put a deposit down.”

“That’s for the rent!”

“We can pay that later. Why are you always causing problems, Peter? . . . We need this for our image and to enrich our lives. Can’t you imagine how great it will be driving around in this car?”

“We don’t know how to drive!” I yelled.

“We’ll get a chauffeur, then!” he barked.

It goes on like this, McGough relaying and reveling in the fabulousness of his life with McDermott, their shared iconoclasm and near-total lack of impulse control. McD (as McGough calls him) shines as a real piece of work—and a star. His persona is completely exasperating, and yet there are moments when you can’t help but fall for his charms:

Whenever we bought groceries, McD would remove all the plastic and Styrofoam they were packed in and empty the contents into cookie jars or a fruit bowl and take the plastic to a recycling center. . . . After taking the modern labels off the canned food, we had a hard time figuring out what was in which can. In the morning, he’d pull the elastic thread from his socks and wear garters to hold them up. . . . In some ways our slum tenement home on Avenue A was comforting and transporting . . . a place out of time.

By the time I entered art school in the mid-2000s, McDermott & McGough’s reputation had diminished significantly. Even so, my classmates and I were aware of the time experiments—costly, bizarre, and obsessive historical reenactments intended as a semi-satirical rebuke to the hypocritical moral panic of contemporary times. They routinely tore out the heating and electrical from whatever apartments they rented, preferring candlelight, icebox, and fireplace. They always dressed in perfect period attire, appearing in public as nineteenth-century dandies. They were even known to commute over the Williamsburg Bridge in a horsedrawn buggy from time to time. After I met Peter at an art opening some years ago, I became convinced that those stunts were more than just a gimmicky penchant for old-timey styles. I am more certain now, having read the memoir, that the experiments, along with the paintings, drawings, and photographs, were impressive artistic achievements, executed without nostalgia or cynicism. Indeed, McGough’s anticynical nature comes through just as well in his writing. Unlike in many memoirs by well-known artists, there is no self-aggrandizement here, no unattractive score settling, no claims laid to misbegotten legacies, no tedium. McGough is somewhat self-deprecating and good-humored overall, a delightful raconteur. His conversational style translates real life into literature effortlessly. Crack open the tome and let Peter regale you:

We didn’t have a television or radio and we hardly ever looked at newspapers, since McD liked to get his news from hearsay and gossip. I knew of [the stock market] crash, but I didn’t think it would affect the art world or us. . . . We had never saved a penny, however. In addition to the Model T we had bought a 1925 Model A truck that didn’t work and a pile of antiques. We had a big staff—as many as fourteen people which included a chef preparing lunches at one point. There were also three horses, handmade saddles, boots, wagons, three properties, three automobiles, fancy restaurants like the Odeon, Bar Pitti, and Il Cantinori, and parties and many bills that we didn’t pay.

Halfway through the book, McGough interrupts himself to insert a startling observation. After beginning a paragraph with two sentences about the death of an art-world acquaintance in 1984, McGough writes, “It’s almost impossible to convey to a young person today what it was like then, when so little was known about AIDS.” The aside marks a change in the narrative’s mission and focus. At regular intervals in the book’s second half, McGough clocks the sudden deaths of many friends and acquaintances. No longer a book solely about an interesting art career, the memoir shifts gears as McGough dwells on the unlikelihood of surviving the epidemic that was killing his community.

“I’ve seen the future and I’m not going” is a quote from cheeky McDermott, intended to announce the artist’s repudiation of all things disposable, accelerated, and consumerist, a pseudoprophetic declaration of the philosophy supporting the pair’s entire undertaking. For McGough, who tested positive for HIV in 1997, the epigram takes on a second meaning, intoning a grimmer reality. With tens of thousands of people dying without meaningful explanation or hope of a cure, McGough couldn’t help but see his own future and realize he wasn’t going, far too aware of the fast-approaching day when he would most likely also disappear from AIDS.

This is not a spoiler, since we know that McGough lives to tell about it, but his harrowing battle with AIDS is indeed a close call; he very nearly departed. When McDermott abandons his partner for a new life of tax evasion in Ireland, our storyteller struggles to cobble a life for himself, all alone, with no money, and in rapidly declining health, with fewer and fewer options for survival. If it is almost impossible to convey to a young person today what the experience of AIDS was like in the ’80s and ’90s, chapter nineteen succeeds verily. McGough, weighing less than a hundred pounds and covered head to toe in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions, tries everything from raw-food cults to the latest medical science (abandoning it in favor of an alternative healing method found somewhere in New Jersey), all while climbing up five flights of stairs every night to his hovel above a seedy erotic-massage parlor in Times Square. The conveyance is stupefying, terrifying, and exhausting.

Somehow McGough makes a full recovery, as if by miracle. He reunites with McDermott for another art show. That’s when the reader starts to get a fuller picture of what makes I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going special. McGough reminds us that friendship, frivolity, and romance are magical, transporting, and lifesaving endeavors—even if, at the same time, they can drive you crazy or make you go broke. Meeting anyone at all is miraculous, but what I still have trouble believing, even though I’ve just read all about how it happened, is that these two visionaries met in a theater and decided to devote the long haul of their lives to a wildly unique and total experience of difficult art, even as they and their friends lay dying in sickbeds.

AIDS is the only truly evil villain in the book, making the rest of the cast of shallows appear only disappointing or confused in comparison, mere inconveniences in an otherwise beautifully complex life story. AIDS bankrupted multiple generations on the art scene, and even more on a global scale, depriving us of millions of individuals with countless unknown deposits of talent and creativity. I’m grateful we still have Peter—and, though I’ve not yet had the pleasure of meeting him, David too.

Sam McKinniss is an artist living in New York.