THE LONDON ART WORLD IN THE 1980S was “hedonistic, greedy, self-serving, go-getting opportunistic mayhem,” Lubaina Himid remembered in 2001. “Everyone who shook or moved in artistic semicircles or political whirlpools was a deserving dartboard. I took aim and threw.”

Born in 1954 in Zanzibar, Tanzania, Himid emerged in the ’80s as a leading figure in Britain’s Black Arts Movement, exposing the wages of empire and affirming black diasporic experience through many media, most prominently painting. Her celebrated 1986 tableau A Fashionable Marriage pastiches the eighteenth-century painter William Hogarth’s satirical series “Marriage A-la-Mode” in a delicious pillory of contemporary England’s reactionary ruling class and its art-world courtiers. Himid cast Margaret Thatcher in the role of the dissipated countess, Ronald Reagan as her suitor, and an unnamed white male art critic as the corpulent, sycophantic castrato. She interpolated herself in the role of the black servant, a move that spatially centered a black woman artist while also suggesting the asymmetrical power relations that conditioned her selective inclusion in the mainstream art world.

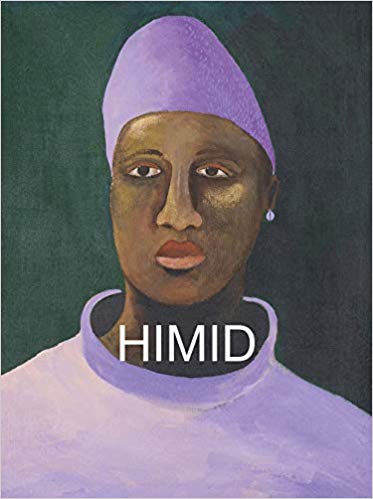

Work from Underneath is the catalogue for a fairly low-key exhibition of Himid’s work at the New Museum, which comprises a selection of works made this year rather than a broad overview of her achievement. Its title comes from her “Metal Handkerchief” series, a suite of small pictures pairing bright, flatly painted images of screws, saws, pulleys, and other hardware with phrases from safety manuals. Redeployed by Himid, these utilitarian advisories—KEEP MOVING PARTS LUBRICATED; GIVE WARNING OF UNDUE STRAINS—become “strategies for survival,” working in an emendatory mode different from the burlesque satire of A Fashionable Marriage.

With colorplates of works dating from 1999 to the present, and brief contributions from curator Natalie Bell and art historian Jessica Bell Brown deftly touching on various stages of Himid’s career, the book covers a greater temporal span than the show but feels similarly abbreviated in proportion to the scope and significance of its subject’s three-decade career. Its overall effect is to leave the artist teasingly underexplained. Whether this is generative or limiting depends, of course, on the reader. “What it is to perceive depth,” theorist Fred Moten states in his contribution, “is not the same as what it is to feel it.”

Moten’s text is a dense and dazzling, sometimes exasperatingly difficult, ekphrastic essay on Himid’s 1999 diptych The Glare of the Sun (Plan B). For Moten, the interior represented in the painting—an unpeopled meeting room scattered with austere slat-back chairs—evokes myriad spaces of diasporic political organization and sociality, “filled with underhabitation’s sighs and the asignifying marks they leave.” Moten’s poetics, thick with his characteristic refusals and excesses, seem strategically calibrated to work against the discourse of cultural visibility that has both amplified and delimited Himid’s work. This is fitting: Reflecting on A Fashionable Marriage, Himid voiced skepticism about triumphant narratives of arrival. “I believed that we as black women artists held the centre,” she wrote. “In fact, we rented rooms there.”