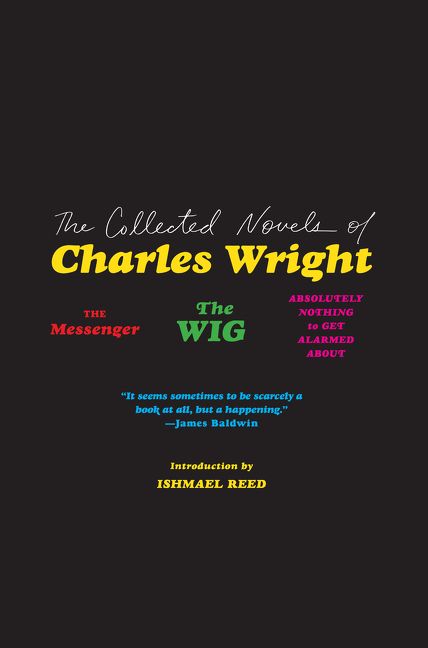

The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s been enough. Through the dedication and (even) fervor of his steadfast readers, Wright’s sardonic, lyrical depictions of a young black intellectual’s odyssey through the lower depths of mid-twentieth-century New York City have somehow materialized in another century, much as Wright once imagined himself to move through time and space: “like an uncertain ghost through the white world.”

It’s tempting to think of Wright’s unnamed alter ego in these mostly autobiographical novels as Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, emerging tentatively from the city’s underbelly at the dawn of the 1960s, just as the civil rights movement was gaining momentum, but still condemned to occupy the “lower frequencies” of a forbidding metropolis, in a state of what the biracial Beat poet Bob Kaufman characterized as “solitudes crowded with loneliness.” As with Ellison’s hero, Wright’s protagonists are often mistaken in these novels by people on varied social levels for being anything other than their true selves.

The point is marked harshly, if almost haphazardly, as far back as The Messenger. One of the protagonist’s delivery assignments takes him beyond Manhattan to the “serene, green world of Manhasset, Long Island,” where a small boy with a space helmet and Davy Crockett T-shirt aims a water pistol at him and shouts, “Hey you! Chinese Boy!” This disagreeable interlude prompts a comparably unpleasant reverie of a Missouri childhood during which the narrator was both affronted and cold-shouldered by whites for being black while withstanding insults from black friends for being “yellow” or “shit-colored.” In sustaining the bruises from these bigotries (“They called me dago as a child, before my curls turned to kinks”), Wright’s narrator also recognizes that they forged the foundation of his lifelong status as an outsider, someone who carries his understanding of who he is through mood-swinging tumult and the hand-to-mouth uncertainties of his life among the prostitutes, drug addicts, and dealers. These were his neighbors and, at times, friends in the city’s grubbier precincts and side streets during the Kennedy New Frontier years.

Wright’s hard-boiled protagonist is also a street hustler, augmenting his scant income as a messenger with whatever he picks up from being picked up for sex by women and men. Not all the trysts are consummated. One Saturday morning finds him reading Hemingway short stories on a park bench in the East Fifties when a “middle-aged man” with a “whiskey-ad face” asks him to survey the first editions in his apartment. The narrator gets off on the books, but declines his host’s advances.

There are other such encounters in The Messenger: sadder, funnier, and darker. But one mentions this occurrence—and Wright’s plots are mosaics of occurrence—to bring up the author’s affinity for Hemingway, whose stories also buck Wright up in Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About. Other influences come up in these books—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Nathanael West, and Langston Hughes—and they all contribute to the bone-dry fatalism and bruised romanticism that Wright’s protagonist carries around like weapons. Such attributes don’t always protect him from pain, embarrassment, or the loneliness of walking barren streets “saddled with a numb, self-centered despair.” But they do afford the narrator enough cool composure to tell an overbearing police sergeant to stop intruding on his personal space.

When the reader gets to the second of these novels, 1966’s The Wig, it feels as though the flamboyant astral boogie of George Clinton’s Funkadelic stormed into the middle of a bop quartet’s lovesick ballad. The mean-streets milieu is roughly the same, this time centered mostly in Harlem, where we meet Lester Jefferson, a rambunctiously outgoing and terminally callow variation on Wright’s urban-loner persona. Lester is determined to capitalize on the transformative potential of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society with some bold transformations of his own. These begin with the vigorous application of something called Silky Smooth Hair Relaxer (“with the Built-in Sweat-proof Base”), thus bringing to life the eponymous “wig”: a lustrously silken hairdo that so boosts his self-esteem (“I hadn’t felt so good since discovering last year that I actually disliked watermelon”) that he believes nothing less than the American Dream is within reach. Helping him along is one Little Jimmie Wishbone, a shady personage who once was so celebrated a movie star that he was serenaded in the White House Blue Room by a congressional chorus singing “He’s a Jolly Good Nigger.”

The imagery and the circumstances swing hard and wild in this surreal vision of a 1960s New York populated with such exotic characters as Sunflower Ashley-Smithe, a “thoroughbred American Negro” record producer; Sandra Hanover, née Alvin Brown, “a male-femme in sundown antelope costume and matching boots” along with a five-o’clock shadow; and the mysterious Mr. Fishback, a necrophiliac funeral director. Despite his attention-getting locks, Lester has trouble finding work until he scores a gig requiring him to dress up in a chicken suit to promote a fast-food franchise (“$90 for five and a half days, plus all the chicken you could eat on your day off”).

In drastic contrast to its more ruminative predecessor, The Wig reads as though it could have been airlifted from the present day. Back when Jim Crow was still reeling from the blows it took from civil rights legislation, Wright’s heedless, insolent appropriation of degrading stereotypes to challenge status-quo racial presumptions was tonic for young black writers seeking escape from the naturalism white critics like Irving Howe generally expected from them. The Wig anticipates the work of Fran Ross, Paul Beatty, Darius James, and Ishmael Reed, who in his introduction to this collection regards the novel as a landmark in African American fiction and elsewhere calls it “Richard Pryor on paper.” The Wig feels as though it was talked up in torrential bursts rather than written down, balancing its honest rage with narrative vigor.

If The Wig’s rococo audacity evokes the dizzying convergence of upheaval and possibility marking the go-go ’60s, then Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About comes across like the bleak morning-after of the Nixon era. Assembled largely from columns Wright wrote for the Village Voice, his final novel represents a drastic shift back to the blue-tinged melancholy of The Messenger and to that book’s protagonist, who, despite having gained some renown as a writer, is still struggling to find steady work and hold on to a place to live. Absolutely Nothing’s beginning finds him in the Salvation Army Bowery Memorial Hotel, fighting off insomnia and “arrogant cockroaches” as he drinks his way to something resembling consciousness. Even through an alcoholic haze, his boldness, resilience, and facility with language remain intact as he reminds the reader who he is and what he’s there for:

Solitary watchman. Lantern held high. Peering out at friends, strangers. Desperately trying to get a reassuring bird’s-eye view of America. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s sunny philosophy had always appealed to me. I believed in the future of the country. At fourteen, I had written: “I am the future.” Twenty-six years later—all I want to do is excrete the past and share with you a few Black Studies.

And so he does, conducting a tour of a New York City enervated by a free-falling economy and imploding desires. As with the most interesting American writing of its era, Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About wanders comfortably between journalism and fiction, blending the narrator’s deepening spiral into alcoholism and depression with compassionate and persuasively rendered set pieces about others in his social circle who experience similar travails along the precipice of urban squalor: cat lovers and dognappers, drug addicts and winos, lovers and haters. “Like an addicted entomologist, I am drawn to people. Let them flutter, bask, rest, feed on my tree. Then fly, fly. Fly away. Goddammit.” His sense of humor remains intact, but just barely, and at times you want to avert your eyes from the scenes he depicts, e.g., a “fat, laughing Chinese girl about three years old” falling to the ground on a pile of dog excrement.

And still Wright manages to inspire, even when he’s staring at you from the bottom of an empty bottle. When I first read Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, in my relatively secure twenties, I imagined how living along the sawtooth edges of New York City in those economically stressed mid-1970s would, for any young black writer, be enthralling and disheartening all at once. Even at his most marginalized, Wright wrote with a sense of style and intensity of vision that allowed me to believe I could live, grow, and strain for enlightenment within the isolation the book evokes. That’s why, I suppose, Wright’s meager literary output won’t go away: As much as his Fitzgeraldian dreams were atomized by life, he never stopped taking it all down, turning it into art, and being true to his calling.

Maybe one should look not to Fitzgerald but to Pryor for the most apt comparison. In a routine about a trip to Africa, Pryor describes a wildlife tour where he caught several animals in the act of being their predatory or preyed-upon selves. Among the latter was a giraffe that had extracted itself from pursuing lions. “Half his ass,” Pryor recalled, “was eaten off. Just hangin’ there like that. But the mothafucka had an attitude like, Fuck it! I’m alive!”

Gene Seymour is a writer living in Brooklyn.