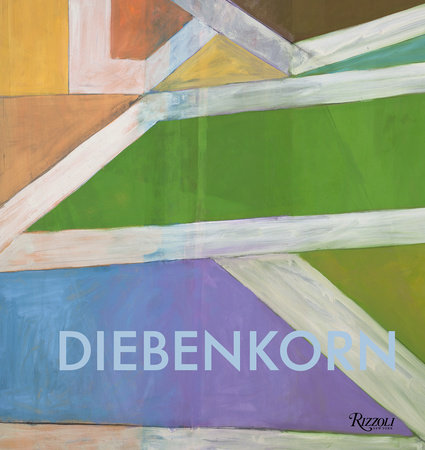

WITH ITS SOFT YET VIBRANT YELLOWS AND REDS in a floral-patterned wallpaper set against an array of angular blues, Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad, a 1965 painting by Richard Diebenkorn, evidences the profound influence of Matisse. Diebenkorn saw works by that artist in 1964 at the State Hermitage Museum and would come to share his strong geographic identification with a sunny locale, replacing the French Riviera with the state of California, his home for most of his creative life. Titled after the Santa Monica neighborhood where he kept a studio beginning in 1967, his widely acclaimed “Ocean Park” series is often thought to be inspired by aerial views of landscapes. Although rigorously geometric, these paintings suggest both a breezy languor and open space, qualities that at one time constituted the very definition of the Californian sensibility. Along with those near-iconic works, this retrospective volume presents less familiar material—still lifes, portraits, and landscapes—completed while Diebenkorn lived in Berkeley from the late ’50s to the mid-’60s. A darker palette and a penchant for shadows generate the brooding sense of life at the continent’s edge that suffuses these images. This effect owes only in part to the contrast between representation and abstraction; it’s easier to impute emotional states to portraits than to Color Field grids. Still, his blurred depictions—of ranch houses outside San Francisco and an Oakland vista in which heavy blue-gray clouds weigh upon rooftops—carry an unmistakable impression of interiority. The streets are unpeopled, with life going on indoors, and the landscapes evoke an atmosphere of vigilant apartness.

From this representational period, the most eloquent joining of West Coast sensuality to a contemplative inclination is found in the portraits. Frequently taking his wife, Phyllis, as his subject, the artist explored quiet, solitary moments in a manner reminiscent of Edward Hopper. Seated Figure with Hat, 1967 (above), initially strikes us as a study in color dynamics—the bold strokes of yellow energetically enclose the placidly rendered tones of her clothes. The richness of the chromatic interaction supports and enhances the figure’s subjectivity. She turns away from our gaze; her hat hides her face. Amid expansive, almost sentient light, she retreats within herself to regard something that lies off in the enveloping radiance. Diebenkorn’s control of composition, brushwork, and tonality complicate what otherwise might be read as merely an easeful pause in paradise. Instead, he offers his own version of the Californian moment—voluptuous pensiveness.