Readers in the distant future will surely note that a good number of books published in the late 2010s registered how dramatically the political landscape shifted while they were being written. Philosopher Susan Neiman’s Learning from the Germans is a case in point. The director of the Einstein Forum in Potsdam, Neiman decided to take a fellowship in Mississippi midway through Obama’s second term, not long after the murder of nine African American churchgoers in Charleston. In the shooting’s wake, Republican governors of South Carolina and Alabama got rid of the Confederate battle flags that had long flown over their capitols, and Walmart stopped selling the thing. The call to take down Confederate monuments of all stripes, once a fringe campaign, became a reality in several cities in the coming months. By the time Neiman had finished her fellowship, Donald Trump was in office, the monument campaign had reached the fateful stop of Charlottesville, and the president weighed in on the homicidally racist Unite the Right rally with his monumentally insipid “very fine people on both sides” hot take.

Two summers earlier, in 2015, in the full horror of the massacre, it was easier to feel that a time of reckoning had necessarily arrived, a feeling that informs Neiman’s book, which combines reporting from the Deep South and contemporary Germany and reflections on German memory culture and the long struggle to come to terms with the past. One of the more unflinching aspects of Learning from the Germans is her conviction that American and southern realities are more flexible, or at least less inflexible, than most would think. Neiman, who spent her childhood in Atlanta, reasons that the German process took a good five decades to turn the corner; if you take the Civil Rights Act rather than Appomattox as your year zero, the time frame is roughly comparable. “If even those raised in the heart of darkness needed time and trouble to see the light, why shouldn’t it take time and trouble to bring Americans—nurtured for years on messages of their own exceptional goodness—to come to terms with homegrown crimes?”

Neiman’s book comprises two parts. The first is dedicated to the historical underpinnings of the German reckoning with Nazism and the Holocaust beginning in the early ’60s, with television broadcasts of the Eichmann and Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which led a younger generation to ask, for seemingly the first time, about the complacency and complicity of teachers, politicians, and above all fathers. (“Being German in my generation,” the author Carolin Emcke, born in 1967, tells Neiman, “means distrusting yourself.”) Learning from the Germans narrates the subsequent political and cultural evolution, including Willy Brandt’s 1970 Kniefall in penance to the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Historians Debate of the 1980s, and the 2003–2005 construction of Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial, a site Neiman dislikes for the vagueness of its abstract form but whose gestation was admittedly long and difficult. Reunification posed a particular set of challenges to how Nazism and the Holocaust were publicly remembered; she contrasts the record of the former East Germany with that of West Germany and largely defends the avowed antifascist state from the charge that it failed to address the German past with anything comparable to Western efforts. Three decades after reunification, the extremist AfD party explicitly frames what it calls a “guilt cult” and threatens the success of the postwar project. Yet no other country (at least in Europe or North America) has made anything like the strides Germany has toward facing the legacy of national evils, whether colonialism in Britain and France or slavery and Jim Crow in America. Only in 2009 did the US Senate approve a resolution apologizing to black Americans for slavery.

The second part of Learning from the Germans is a survey of the new and old sites of public memory in Mississippi and neighboring states: places like the Delta town of Sumner, where a jury quickly acquitted two men of the murder of Emmett Till; Holly Springs, where an excavated slaves’ residence (which are quite rare, given the flimsy materials they were made of) sits in uncomfortable proximity to the town’s antebellum homes, their magnolia-and-moonlight tour guides, and unreconstructed Confederate reenactors; and Montgomery, home to the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the first site dedicated to marking the memory of thousands of victims of lynching. There is a particular focus on Oxford, the university town at the center of the civil rights movement. Like much of what Neiman surveys, reconciliation at Ole Miss is a mixed bag. Student groups are politically active, leading the charge that got the school to stop displaying the state flag (an especially irksome decision in the eyes of Mississippi Republicans, who, comically, like to talk about Oxford as the Berkeley of Dixie). Yet the “contextualization” efforts to address the Johnny Reb statue and to mark James Meredith’s integration of the school in 1962 have been less successful, and many Greeks and alums are indifferent at best when not hostile or volatile.

Neiman acknowledges both the limits and possibilities inherent in her comparative endeavor: “Seen in one light, the differences between German and American racist histories are glaring. Seen in another, what’s clear is what the similarities can teach us about guilt and atonement, memory and oblivion, and the presence of the past in preparing for the future.” Most of her interlocutors here and abroad remain skeptical or find the analogies invidious. “Nearly every German I know,” she writes, “from public intellectual to pop star, laughed out loud when they heard I was writing a book with this title.” In the South, she finds people who are interested in the German reconciliation process and incredulous that generations immediately after the war excused themselves as victims rather than perpetrators: “‘But surely . . . ’ said a sweet-tempered sixtyish man in Mississippi after I’d explained that the first generation of postwar Germans sounded like nothing so much as the defenders of the Lost Cause version of Confederate history, ‘Surely they knew—at the latest when they opened the camps—that what they’d done was pure evil?’”

Neiman’s interviews are extensive, and she allows the voices of those involved in thinking about how to address public memory to animate her pages. In a chapter surveying a pair of Emmett Till memorials in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, the range is fascinating, from the white Delta planter and president of the National Cotton Council to the African American mayor of the tiny town where Till’s body was found to the gun-nut son of the killers’ lawyer: Neiman’s firmly focused questions of guilt, reparations, and how to memorialize Till’s murder reveal a variety of motives and dispositions. “In the end it is not motives but deeds that matter, as Arendt showed in Eichmann in Jerusalem. It doesn’t matter what moves you: it’s what you do, and leave behind, that counts.”

The future of Confederate monuments, most constructed a half century after the Civil War, lingers over Learning from the Germans. Neiman hails New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu’s 2017 speech concerning the removal of several statues “for its clarity and eloquence.” But she notes too that not long after his speech, Alabama joined Mississippi in banning the “disturbance” of monuments, memorial streets, and buildings “located on public property for more than forty years.”

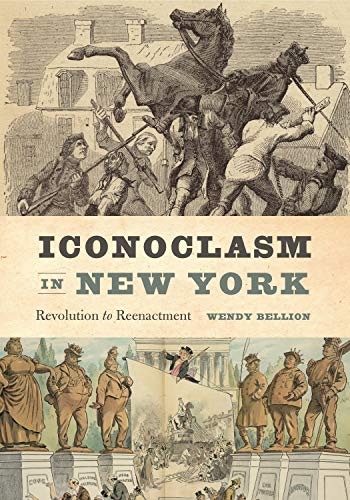

Robert Musil once noted that the thing about monuments is that one does not notice them. “There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument.” Until, of course, they can’t be unnoticed any longer, when the claims that monuments make on collective memory intersect with political action. Art historian Wendy Bellion’s book Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment traces the curious legacy of a monument celebrated historically for its destruction: the massive gilded equestrian statue of King George III, erected in New York in 1770 and hacked to pieces in 1776. Melted down for bullets—one source gives the incredibly precise number of 42,088—the statue, or better, its demise, has become mythologized as a national primal scene. Yet it’s a story wreathed in obscurities, beginning with the fate of the sculpture’s decapitated head, which loyalists somehow secreted back to England before its eventual disappearance.

No less obscure is the painter whose canvas Pulling Down the Statue of King George III, 1852–53, most fixed in public memory the moment horse and king tumbled down: Johannes Adam Simon Oertel, an émigré from Bavaria displaced like so many others by the tumult of 1848. “It was executed,” Bellion notes, “by a newly arrived German immigrant unfamiliar with American history; it was an outlier in the artist’s oeuvre (Oertel later specialized in animal and religious paintings); and it was neither exhibited nor purchased at the time of its creation. There is little in the painting’s early history to explain the renown it would subsequently command.” Oertel painted at a moment when a German-born immigrant artist like Emanuel Leutze could create the work most powerfully associated with the War of Independence, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), and when revolutionary allegories found an enthusiastic reception among New York’s German-speaking exiles. (The German–New York nexus included Karl Marx, employed as a European correspondent for Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune.) Oertel’s canvas showed black and American Indian onlookers; in prints made for mass consumption in the years to follow, these figures were edited out, creating an image as white as the purveyors of the Colonial Revival movement, which repurposed the context of Oertel’s gesture. The fate of the royal equestrian statue and of the Bavarian immigrant’s painting reminds us again that the history of public monuments is never set in stone. Yet another thing learned from the Germans.

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU.