There are a handful of novels in the English literary canon that directly concern domestic abuse. Most of them are light on direct testimony from victims, instead sublimating the violence of the marriage plot into the heroine’s surroundings. In classics like Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, or Rebecca, the reader will notice something wrong with the house long before they see the flaws in the lover.

It makes perfect sense to dramatize the marital home in a novel about intimate torture, because that is where the wife is trapped. Then as now, a spouse who wants to control a woman will limit the sphere of her actions, isolating her psychologically—and physically. The home-as-prison has become a multivalent literary symbol for the bind facing women characters who marry. Gaining the right to occupy the husband’s property has traditionally been one of the purposes of the matrimonial enterprise, but moving in can be the misstep that dooms a bride to misery.

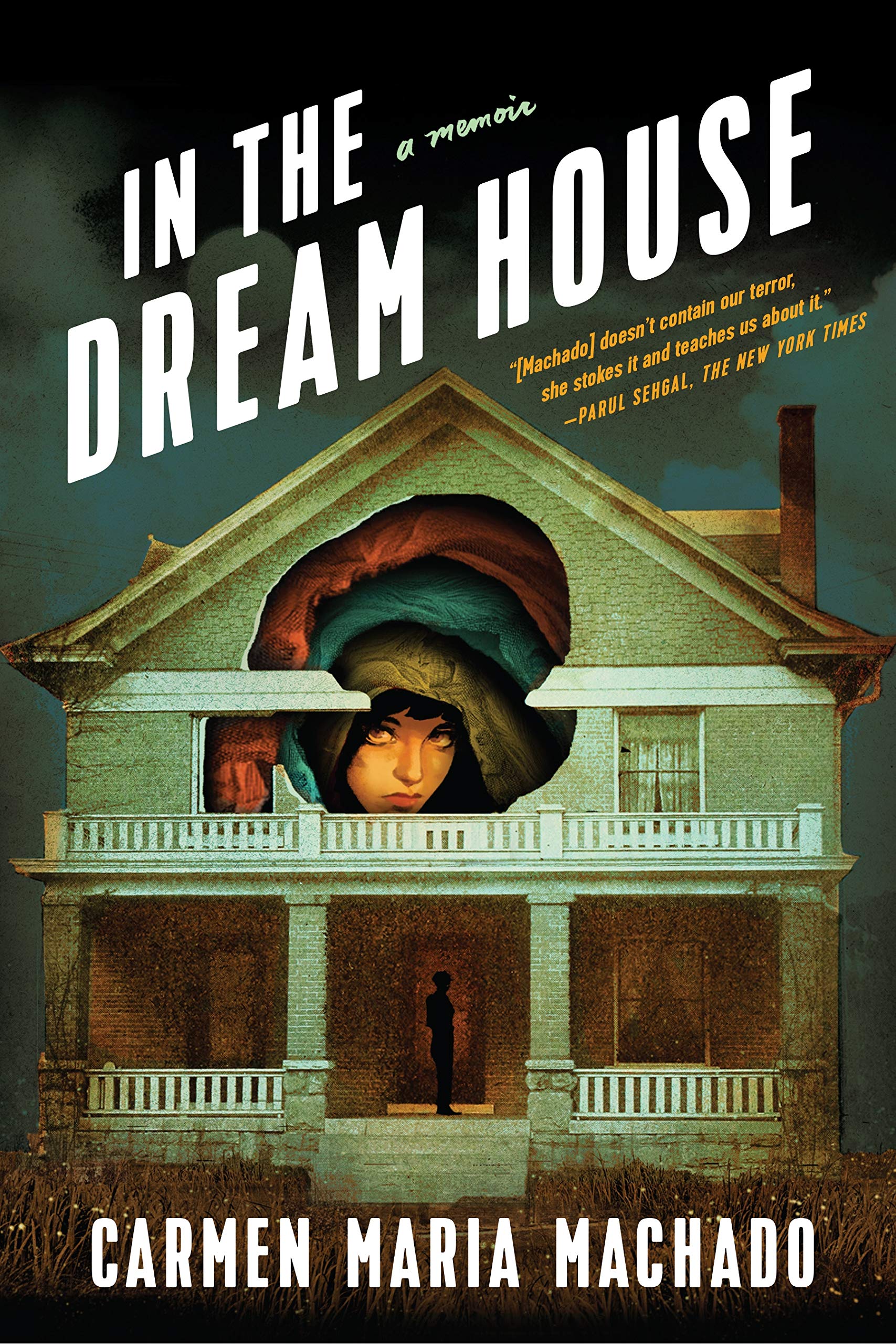

Carmen Maria Machado’s new memoir, In the Dream House, refashions the gothic heterosexual house of horrors into a place where the queer, abused woman can speak in many voices, including her own. Machado has been acclaimed for the ways her genre-bending fiction creates elbow room for queer intimacy; her first story collection, Her Body and Other Parties (2017), won a Shirley Jackson Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award. Her new book tells the story of sleepwalking through a relationship with a violent, controlling, and perpetually enraged woman, whom she stayed with for far too long. They met at a dinner, where Machado noticed the woman’s “dazzling smile” and “raspy voice,” which sounded “like a wheelbarrow being dragged over stones.” Soon after their first meeting, Machado’s new girlfriend was driving recklessly and refusing to give up the wheel; screaming at a cowering Machado then pretending nothing had happened; gripping her arm with bruising fingers, weakly apologizing, and moving on.

Machado is not a Victorian waif in a nightgown or a straight woman; she wasn’t forced to stay in the home she shared with the ex. On the face of it, the story’s queerness makes Machado’s use of a haunted-house motif a counterintuitive choice. But that very paradox is the subject of In the Dream House: A prison can have unlocked doors. It’s a maddeningly complex proposition, although, like all paradoxes, it seems simple enough from the outside. Machado dismantles the quandary in more than a hundred short chapters, each named for a different facet of the house’s emotional architecture: “Dream House as Inciting Incident”; “Dream House as Time Travel”; “Dream House as Famous Last Words.” As the house falls apart under her memory’s scrutiny, Machado works like a kind of forensic carpenter, sifting through the wreckage for what went wrong.

Machado’s premise is an absence. Specifically, she wants to describe the “topography” of holes in the historical and literary record of human relationships—in other words, in “the archive.” In “Dream House as Ambiguity,” she writes in a direct and scholarly style, explaining how abuse between same-sex lovers has gone totally unrecorded. She cites an 1811 legal judgment by Lord Meadowbank, who ruled that women’s genitals “were not so formed as to penetrate each other, and without penetration the venereal orgasm could not possibly follow.” Machado reads the opinion as a kind of social axiom of lesbian nonexistence. And who could conceive of violence between people who don’t exist?

In her own time, Machado writes, queers have had their own reasons for suppressing news of violence within the home camp. In “Dream House as Sniffs from the Ink of Women” (a reference to one of Norman Mailer’s nastier pronouncements), Machado recalls that she “came of age in a culture where gay marriage went from comic impossibility to foregone conclusion to law of the land.” But the fear of queer life being misrepresented by straights has not disappeared along with the prohibition on marriage. Admitting to queer-on-queer abuse can feel tantamount to endorsing the “specter of the lunatic lesbian,” as Machado puts it. Homophobia always casts queer women as mentally deviant, and it has been in lesbians’ interest to show the world otherwise. If she could say anything to her ex-girlfriend now, she writes, it would be, “For fuck’s sake, stop making us look bad.”

As she writes deeper into her own past, Machado’s voice shifts. She opens the book in the first person, speaking like a lecturer describing the knot of problems she’s about to attack, but later begins to address her former self as “you.” Gone is the academic musing on the archive, and with it, the reader’s sense of direction. There’s no index to explain which sections treat the Dream House literally or figuratively—Machado leads us into a thicket of mixed, and conflicting, metaphors.

The most directly descriptive section is “Dream House as Set Design.” It is “a nondescript house in a neighborhood on the outskirts of Bloomington, Indiana, a few years after the close of the aughts.” Everywhere, greasy cardboard boxes totter, evidence of her girlfriend’s aristocratic indifference. It reminds Machado of the palace from Angela Carter’s story “The Tiger’s Bride,” which appeared “dismantled, as if its owner were about to move house or had never properly moved in; The Beast had chosen to live in an uninhabited place.”

This casual reference acts as a triangulation point, linking Machado’s personal memories to her memories of literature, fraying the distinction between the real and the imagined. Other Dream Houses overlay the set design: In “Dream House as Memory Palace,” Machado draws a map to her own past as a sexual being. Now the driveway is lined by “all the boys who liked you as a girl,” the Colins and Seths and Adams of yesteryear. Boyfriends live in the office, the bathroom. The cardboard boxes give way to a wisp of memory about a guy named Paul with a “downy ass” and a kind heart.

With each chapter, Machado splinters her topic—a house where one woman hurt another—into constituent parts. Sometimes she reaches for works of cultural criticism that ought to have helped her understand what was happening. These sections are often a page long or less, and named for literary genres or conventions: “Dream House as Comedy of Errors” and “Dream House as Chekhov’s Trigger.” A section on Machado’s childhood (“Dream House as Bildungsroman”) lingers on her teenage crush on a pastor with boundary issues, before the next (“Dream House as Folktale Taxonomy”) takes us through a crash course in doomed mermaids and princesses.

Machado’s strategy disorients the reader, but that feels like an intentional choice. After all, a person always feels disoriented within their own biography: Nothing quite makes sufficient narrative sense at the time it is happening, but the fragments layer upon one another to form the story of a life. A sense of I should have known better hovers over the text, as if Machado, being so well read and smart, ought to have been able to think her way out of the abusive relationship. Of course, critical analysis only works in retrospect. By blending her own critiques (of the movie Gaslight, of the lesbian pulp romance) with memories of terrible mistakes in love, Machado shows how ill-suited literary scholarship is to the task of seeing one’s own predicament clearly.

There are hundreds of ways to be haunted, In the Dream House shows, but not all of them have been written: Via a delicate polyphony of storytelling and criticism, Machado lays out how the literary tradition of domestic abuse has both expressed and muffled the experiences of women in danger in their own homes.

“You pile up associations the way you pile up bricks,” reads a quote by Louise Bourgeois, one of the book’s epigraphs. “Memory itself is a form of architecture.”

In his 1930 work Civilization and Its Discontents, Sigmund Freud compared human memory to the multilayered architecture of Rome, where ruins from the ancient past (and later restorations of those ruins) appear simultaneously mixed up with the “jumble of a great metropolis which has grown up in the last few centuries since the Renaissance.” Walking down the palimpsestic streets of Rome, ordinary chronological time melts away, and the past and present merge. In the same way, every moment of our lives carries every other experience we’ve ever had. The mind does not run on chronological rails—it is an infinitely reactive machine for cross-referencing memory.

Though Machado doesn’t cite Freud, her construction of the Dream House as a place of infinite rebuilding and overlayering does take her to the same conclusion. She builds the house as a pathological memory organ, where her gaslighted former self is cut off from the rest of the world in a vortex of abuse. Her fear seeps back into her physical surroundings, creating a cycle of repressed emotion that only exacerbates her terror.

By taking a gothic idea and exploding it outward through different modes of interpretation, Machado transforms the “holes” in the archive. They are no longer absences, but spaces for the queer, abused woman to reckon with her memory to its fullest extent. In doing so, Machado also expands the narrative of victimhood, and opens up a new door in the house: It leads to self-knowledge, and escape.

Jo Livingstone is a writer based in New York, currently at work on a book about medieval women’s mysticism.