Even when a photograph of a wounded or suffering child becomes familiar, it retains the power to unsettle. The smudged face of a sharecropper’s daughter, children arrayed behind barbed wire at Auschwitz, a starving Biafran child, a nine-year-old girl seared by napalm in Vietnam—these images still disturb viewers and prompt strong responses. Yet, as Susan Sontag argued in On Photography, it’s difficult to measure their ultimate utility: “The knowledge gained through still photographs,” she wrote, “will always be some kind of sentimentalism, whether cynical or humanist.” That propensity for sentimentality—and its necessary appropriation of others’ pain—is routinely manipulated toward political ends.

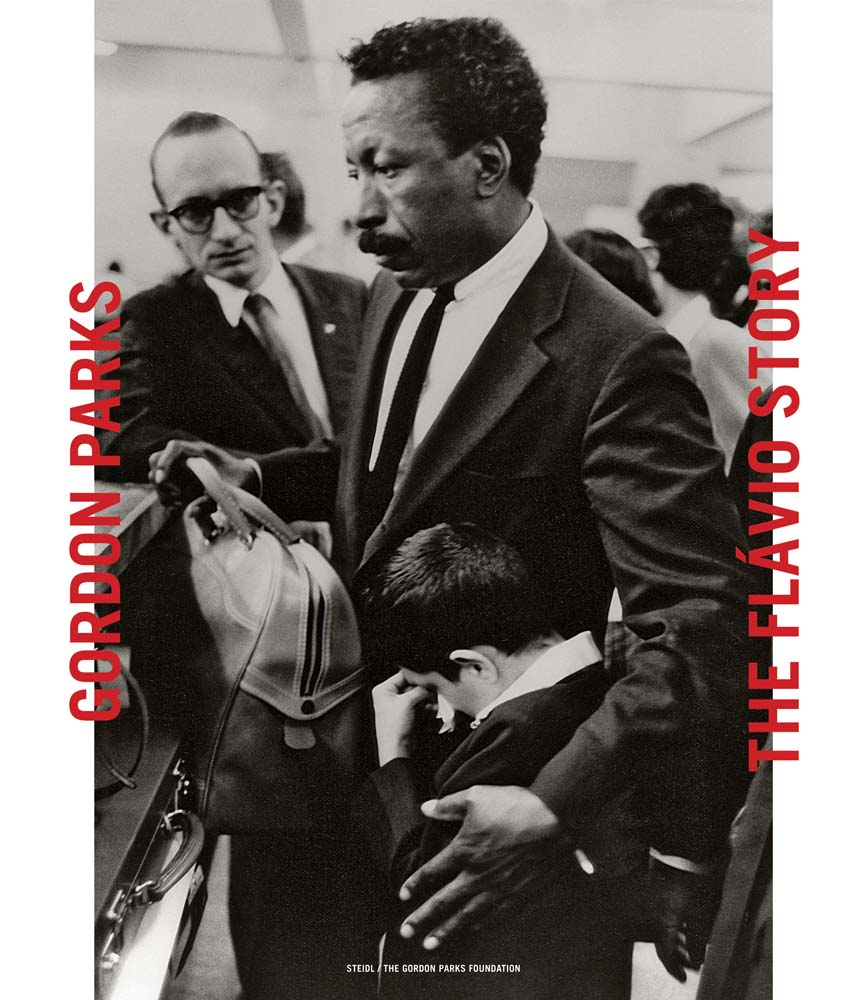

And those ends can be entirely contradictory. In 2016, a photo of a bleeding, dust-covered Syrian boy whose home had been bombed by government forces fueled worldwide calls to end the war; months later Syrian state television aired video of the boy—healthy and seemingly happy—as his father decried the use of the photo and voiced support for the regime. Something similar occurred in 1961 with Gordon Parks’s images of an impoverished child in Rio de Janeiro. In the spring of that year, Life magazine sent the acclaimed African American photographer to Brazil to document poverty in the hillside communities known as favelas. A recent show at the Getty Center in Los Angeles and its accompanying volume, Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story, reveal how images meant to serve as political propaganda sparked a genuine outpouring of support for one poor boy and his family yet left uncertain consequences in their wake.

Throughout the 1940s and ’50s, Parks had chronicled the effects of economic and social segregation on black Americans. As an artist with an activist impulse (“I use my camera as a weapon,” he once declared), he was an apt choice for Life editors working to advance Kennedy’s Cold War agenda. Launched just after the president’s inauguration, a series of special features—“Crisis in Latin America”—emphasized the threat posed by Fidel Castro and aimed to substantiate an urgent need for economic intervention. While combating poverty was a goal shared by Parks, it’s unclear how aware he was of these behind-the-scenes machinations.

When Parks arrived in Rio he teamed up with José Gallo, a local Time Inc. employee who would serve as a translator and guide. They ventured into a notorious favela, Catacumba—the catacomb—and met the da Silva family. Parks’s editor had instructed him to document the life of a destitute family—and the Silvas certainly were that. The parents, José and Nair, had eight children, and they all lived in a single room with a corrugated metal roof, a single bed, one crib, and wooden boxes for furniture. Raw sewage ran nearby; stray dogs roamed free. Twelve-year-old Flávio, the eldest child, appeared to be responsible for the care of his siblings and the household in general. Parks decided to focus on the boy’s daily life, intrigued by his maturity amid burdensome circumstances. In Flavio, his 1978 memoir of the experience, he recalled encountering the boy hauling water up the favela’s steep slope: “He was horribly thin, naked but for his ragged pants. His legs looked like sticks covered with skin and screwed into two dirty feet. He stopped for breath, coughing, his chest heaving as the water slopped over his shoulders and distended belly. . . . Death was all over him, in his sunken eyes and cheeks, in his jaundiced coloring and aged walk.” In subsequent days, Parks witnessed Flávio overtaken by recurrent bouts of asthma; after a visit to a local health facility he learned the boy would likely die within two years. In the magazine, Parks portrays the household’s deprivation and Flávio’s caretaking with a sense of impending doom. In the most striking image, Flávio lies in bed half covered by a ragged blanket, his swollen chest exposed, anguish on his face. The foreshortened perspective and partial exposure of the body explicitly recall Mantegna’s Dead Christ, as does the caption, in which the child-as-father worries about his family: “I am not afraid of death. . . . But what will they do after?” The effect was to imbue the sick, malnourished child’s suffering with meaning far beyond the sociological.

Titled “Freedom’s Fearful Foe: Poverty,” the photo-essay (along with Parks’s diary entries) appeared in Life on June 16, 1961, beginning with a two-page spread showing Isabel da Silva as a toddler crying in what the caption describes as her “shadowy slum world.” The section concluded with another dramatic spread—the ailing, Christlike Flávio paired with a neighbor child, also shot from a foreshortened angle, wrapped in a winding-sheet, surrounded by candles, awaiting burial. The compositional echoes between the two images all but declared the twelve-year-old’s imminent fate.

Guilt and empathy combined to motivate readers: Letters and money poured in to the magazine, organizations sent food and donations directly to Brazil, and an asthma hospital in Denver offered to treat the boy for two years free of charge. By the end of the summer, the “Flávio fund” had collected over $24,000 and he was living in Denver with a Portuguese family while receiving top-notch medical care. In its July 21, 1961, issue, the magazine touted the transformation with a color cover depicting the scrubbed and smiling boy hugging a stuffed animal. A self-congratulatory cover line, “Flávio’s Rescue: Americans bring him from Rio slum to be cured,” introduced images surely calculated to reward readers—Flávio making friends, trying out new shoes, and warily regarding a baseball bat. The dire shot of the sick boy that previously ran juxtaposed with a child’s corpse was now run next to an image of a gleeful Flávio on a playground swing. If this salvation narrative didn’t fully soothe the disquieting sentiments provoked just weeks before, there were also photos of the Silva family in their new “modern” home.

That this apparent triumph of American goodwill illustrated a micro version of what Kennedy planned to do to halt the spread of communism in Latin America—use foreign aid to gain influence throughout the region—wasn’t lost on Brazilians. When the Life articles appeared, the country was in the midst of political upheaval sparked in part by Cold War tensions. O Cruzeiro, a magazine devoted to photojournalism, assigned one of its premier photographers to travel to New York to expose its “shadowy slum world.” Like Parks, Henri Ballot had spent decades documenting victims of economic and racial oppression, particularly the indigenous peoples of Brazil. And, like Parks, when he arrived in the city he sought out a poor family—in this case Felix and Esther Gonzalez and their six children, Puerto Rican residents of the Lower East Side. Ballot’s images mirror those of Parks. Indeed, the American’s photos were included in O Cruzeiro as insets to demonstrate the parallels. The provocation hit home: The photo of nine-year-old Ely-Samuel asleep on a torn and filthy mattress, cockroaches crawling over his body, was later reproduced along with the photo of Flávio in bed in Time, Life’s sister publication. The article, titled “Carioca’s Revenge,” accused Ballot of manipulating his images, perhaps even placing the insects on the boy.

Despite both photographers’ strong sense of social mission, their images served goals they didn’t fully apprehend. The same can be said for their subjects, who were marshaled as proxies in a larger geopolitical duel. Flávio initially benefited from Parks’s and Life’s intervention; his asthma cured, he became quite accustomed to middle-class suburban life. When his treatment was completed after two years, arrangements were made for him to return to Rio. But he asked Parks to adopt him so he could remain in the United States. “I would rather stay here with you,” the boy pleaded. “Don’t you want me?” His return home touched a nerve, prompting a nationalist response from Brazilian newspapers that claimed Flávio now had “airs of superiority.” As might be expected, there was a personal toll. Time Inc.’s Rio bureau chief, who monitored the homecoming, reported that Flávio was “close to traumatic shock.” Over the course of subsequent years, he struggled to assimilate the disruption he had experienced—he was expelled from the private school Life arranged for him to attend—but eventually settled back into his new, old life.

Parks and Flávio reunited in Rio in 1976 when the photographer was working on his memoir. In the foreword to Flavio, he confessed doubt about stories he’d done that altered people’s lives, wondering “if it might not have been wiser to have those lives untouched, to have let them grind out their time as fate intended.” Having found the Silvas’ once-new home in distressing shape, Parks registered the difficulty of redeeming an entire family, if not a vast social ill, in one fell swoop. A photo taken during that visit catches a contemplative Flávio studying a collection of Parks’s images from the 1961 shoot. A twenty-seven-year-old night watchman with a family of his own, Flávio gazes at a picture of his younger brother Mario crying after being bitten by a dog. Although he had come so far from what had seemed a hopeless future, Flávio was discontented; before Parks left, he again asked for help returning to the United States. When he saw this depiction of a suffering child, or the now-iconic image of him as a boy in bed struggling to breathe, what was his reaction after all those years? The pain of that time had been memorialized and mobilized by forces outside his control. Was he conscious of his role in distant political strategies? No one, it seems, thought to ask him.

Now seventy, Flávio attended the opening of the show at the Getty Center. Standing in the galleries, he surely took note of how profoundly the photos in Life had changed his life and how, in their ongoing evocation of both his pain and his joy, they were changing him still.

Albert Mobilio’s most recent book is Games and Stunts (Black Square Editions, 2017).