Few artists have proved as agile in mining American visual culture as Jess. Born Burgess Franklin Collins in Long Beach, California, in 1923, the former chemist reconfigured media clippings, mail-order catalogues, and comic strips into complex, beguiling little universes, omnivorous and imaginative, displaying a formidable literacy of both written word and image. His paste-ups (as he preferred to term them) suggested amalgams of almanacs, the backs of cereal boxes, and pages from Life magazine, by way of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, James Joyce, the chronicles of Oz, and the stoop-front scrapbooks of the artist’s great-aunt Ivy.

Modern-art historians tend to conflate twentieth-century image appropriation and collage with a critique of advertising and commodity culture. But as curator Michael Duncan astutely observes, “Jess’s visual onslaught results in no clear victims or villains.” In his work, “the phony deceptions of advertising and politics can cause a kind of impatient despair, but one that is mitigated by humor and an indefatigable love for play.” If contemporaneous collagists like Eduardo Paolozzi or Richard Hamilton embraced the slick surfaces and Technicolor Pop! of the immediate present, Jess willfully styled his works as monochrome anachronisms, reviving the parlor-room theatrics of late-nineteenth-century photo-collage or the Victoriana-tinged “collage novels” of Max Ernst. Unlike Ernst, who kept his images relatively uncluttered (and thus all the more talismanic), Jess gleefully populated each picture with myriad visual references and one-liners. To complement his dense and dizzying masterwork, Narkissos, 1976–91, Jess created a meticulously annotated two-hundred-page compendium of all his resources, partially modeled after the collective skeleton keys that sought to decipher Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. And yet, even with the artist’s own legend in hand, the image never fully gives itself away. Every fragment may offer another clue, but the mystery itself remains in flux: not just unresolved, but irresolvable.

The artist’s reordering of the world around him extended to the syntax of the text within his compositions. Jess delighted in playing language against expectation. In his Maxims for Minions, 1954, the artist forgoes imagery altogether, using only wordplay to nudge the familiar just over the lip of the nonsensical: “Honesty is the best fallacy. / Depravity is the shoal of wit.”

Love cankers all.

Burn your breeches behind you.

Honour thy feather and martyr.

Dont put all your aches in one blasphemy.

With these wobbly proverbs, Jess slips just under the skin of the vernacular. “Slipperiness” might capture the character of Jess’s semiotics, but it’s impossible to apply this word to his paste-ups, which, while maddeningly dense, have a bone-dry precision, aided in part by the artist’s adherence to the aesthetics of Victorian-era etching and its pseudo-didactic timbre. Jess’s paintings, on the other hand, lie thick on the canvas, with the kind of decadent impasto that calls to mind Wayne Thiebaud’s teacakes. Jess’s foremost series, “Translations” (1959–76), applied this technique to found images, ranging from a man in a bowler hat, alone and clutching a giant pumpkin (A Field of Pumpkins Grown for Seed: Translation #11, 1965), to the Beatles wading in thigh-high waters (Far and Few . . . : Translation #15, 1965), to a portrait of the poet Robert Duncan, surrounded by the elaborate trappings of the house he shared with Jess (The Enamord Mage: Translation #6, 1965). For “Salvages,” a later nine-painting cycle, the artist inserted amendments, echoes, and interventions into his own older canvases, as well as pictures gleaned from thrift stores. As Duncan said of Jess, “What he has achieved is totally his, but in every detail derivative.”

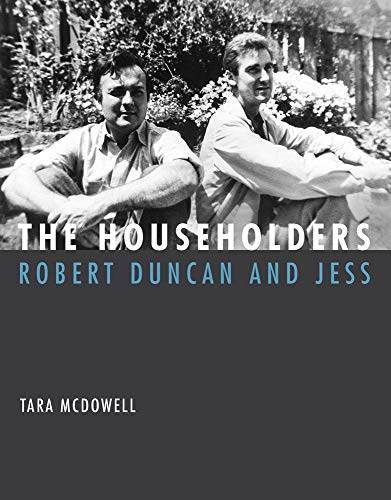

“Derivative” was not intended as a slight. Like Jess, Duncan prioritized appropriation and quotation in his own works. Their relationship, both as lovers and creative fellow travelers, was an echo chamber of ideas, in which they lived with their sources as a kind of surrogate family, condensed in Duncan’s term “the household.” In The Householders: Robert Duncan and Jess, Tara McDowell examines the artistic implications of this arrangement. Both men maintained separate practices, even as those practices occasionally followed parallel trajectories. As Duncan proudly put it, “We have had the medium of a life together.”

Duncan and Jess met in 1949 at a poetry reading in Berkeley. Two years later, they exchanged wedding vows. The import of their same-sex union in midcentury America shouldn’t be undervalued, though the men exhibited a bold casualness about their relationship, a nonchalance that itself was, as McDowell notes, an act of political defiance. Their union would span nearly four decades, almost all of it—excepting only a year spent in Majorca, followed by a brief stint at Black Mountain College—in California, where they existed among the ranks of Bay Area staples like Wallace Berman, Jay DeFeo, George Herms, and Bruce Conner.

If both Duncan and Jess remain regrettably too little known in their respective spheres, The Householders does not attempt to rectify this wrong. Instead, McDowell focuses on the function of the household as it figured within their creative output, as both the site of production and a protective harbor for personal mythologies. She dedicates the first chapter to surveying the couple’s various habitats, including a house on Baker Street, where they lived from 1952 until their departure for Europe in 1955. Here, the pair maintained something of a salon, with Jess serving as the discerning (if not outright catty) gatekeeper. (Allen Ginsberg—whose “Howl” was first read in the gallery Duncan and Jess helped establish—was not permitted into a later home because, Jess alleged, he “wouldn’t understand a chair.”) Their housewarming featured an exhibition by the artist Lyn Brown Brockway; Stan Brakhage lived in their basement. Artworks from friends filled the rooms, which Jess strategically coated in hues of tangerine and “Bermuda blue” to maximize the effect of the daylight as it filtered through the windows. In 1967, the duo took over an old four-story Victorian on Twentieth Street in San Francisco’s Mission District, where Duncan and Jess would reside until their deaths in 1988 and 2004, respectively. As Duncan penned in one of his notebooks, using his trademark phonetics:

The Life we at once lead and follow, that has recognized itself in and realized itseld in, illustrated itself, furnisht itself with chairs, tables, dressers, bedsteads, books, paintings, objects, mementos, dishes, utensils, and the tools and materials of our arts in life, expands now into terms of a house. A house to be “ours” or rather to be us, where the very floors and walls will be terms of our entering life.

McDowell is careful not to read their houses as Wunderkammer. The household, as the two men conceived it, was never a fixed entity or display object, but rather a living organism, with its own will and logic, something that had to be cared for, tended, and even governed. This required an active commitment, a daily affirmation of one’s vows to the household and what it represented. Each man set up his own relationship to that responsibility; Duncan appointed himself as the “guardian,” while Jess—ever one for wordplay—preferred the winsome role of “housewaif.”

Though they cohabited for nearly four decades, commingling their muses and materials, Duncan and Jess kept a careful distance from each other’s work. There is only one recorded instance of a sustained collaboration: Caesar’s Gate, a selection of Duncan’s poems accompanied by Jess’s illustrations, published by Divers Press in Palma, on Majorca, in 1955. McDowell dedicates an entire chapter to this ill-fated endeavor, surmising that “In some real, perhaps unforeseen sense the couple’s intimacy and knowledge of one another emerged as at odds with their mutual need for meaning to remain open and in flux.”

But if Duncan and Jess did not directly collaborate on canvas or page, they were partners in a self-fashioned mythology, a conscious assemblage of their own lineage, rooted in Victoriana and nineteenth-century romanticism. Chief among their self-appointed ancestors was Gertrude Stein, whose portrait with her partner Alice B. Toklas was printed on a pull-down window shade in one of the seven libraries they maintained in the house on Twentieth Street. (In one interview, Duncan lauded Stein as “a hotter Victorian.”) “I had found my life in poetry through the agency of certain women,” Duncan wrote in his own would-be magnum opus, The H. D. Book, a sprawling tome on the avant-garde Imagist poet Hilda Doolittle, who published as “H. D.” In 1959, the same year Duncan embarked on the book, Jess would start the first sketches for his Narkissos. The two men would subsequently dedicate decades of their lives to these portraits. While neither project was ever declared finished, both offered the men vehicles to transcribe, however indirectly, their own autobiographies—or rather, the biographies of the characters they had created for themselves under the aegis of the household.

Later in life, Jess resisted critical readings of his paste-ups that overemphasized his history pre-Duncan and the nearly two years he spent as a chemist monitoring the production of plutonium at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as part of the Manhattan Project. McDowell saves her treatment of the men’s personal histories for the penultimate chapter, “If All the World Were Paper: Salvage and Witnessing in the Atomic Age.” Here, the author’s emphasis is not on combination, but rather dissolution. In the shadow of the mushroom cloud, Duncan and Jess had watched the world they thought they knew fall apart; The Householders shows Duncan and Jess striving to put back together the small corner they occupied. After all, the collage aesthetic that permeated both men’s creative output only holds when it has a solid foundation. McDowell reads their domestic life together—the household—as both this base and the glue.

Kate Sutton is a writer based in Zagreb and an international reviews editor at Artforum.