There’s a scene in André Aciman’s 2007 novel Call Me by Your Name in which a teenage boy ejaculates inside a peach. Later, his older lover, a family houseguest, finds the fruit and eats it in front of him, slowly, deliberately. They’re not even in flagrante delicto; it’s only barely a sex act. “He was still chewing. In the heat of passion it would have been one thing. But this was quite another. He was taking me away with him.”

You already know that Call Me by Your Name involves peach fucking, just as you know that Fatal Attraction involves bunny boiling; such is the power of cinema. In Luca Guadagnino’s adaptation of Aciman’s book, the older man, Oliver, simply licks the sodden fruit, while the younger, Elio, protests. That says all that need be said about the film. Restraint—a lick instead of a semen-filled bite—is the antithesis of what makes Aciman’s book so good. You can hear it in Elio’s words above; the book is about sex, as pleasure, as power, as consumption, both active and passive.

Here’s Elio, imagining seducing Oliver:

And right away I’d take off my pajama bottoms and slip into his bed. If he didn’t touch me, then I’d be the one to touch him, and if he didn’t respond, I’d let my mouth boldly go to places it’d never been before. The humor of the words themselves amused me. Intergalactic slop. My Star of David, his Star of David, our two necks like one, two cut Jewish men joined together from time immemorial.

The first half of the book is like this—fevered, adolescent, dirty, silly. Once the two tumble into bed, though, the story is time’s inevitable passage. Oliver returns to America, where a woman is waiting to be his bride, but this isn’t a story about gay and straight; it’s about sex and death, those old pals. Time pauses for orgasm, but it passes nonetheless. The book’s coda sees the lovers reunite fifteen and then twenty years later, at which point Elio’s beloved father, Sami, has died. It’s bittersweet and well done (if you only know the film you may know the bitter more than the sweet). Every story, even a love story, ends.

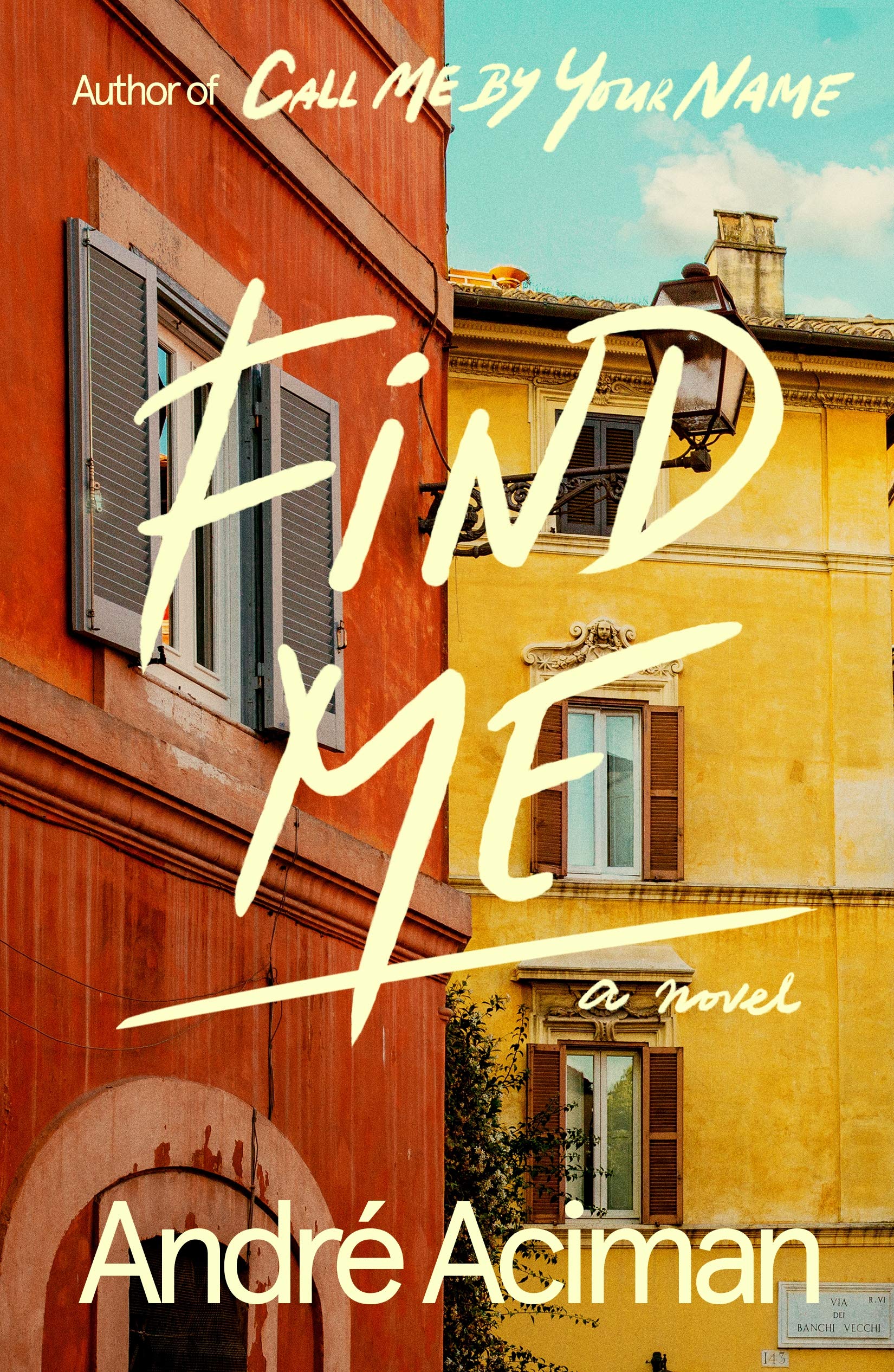

Or maybe it doesn’t. In his fifth novel, Find Me (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27), Aciman returns to the characters Guadagnino made famous and the milieu at which the author is so adept: educated people knocking around Europe. Name is set in the 1980s, though it has no firm location in time. Find Me jumps ahead to the mid-2000s, though the only evidence of this is the characters’ cell phones. Aciman is more interested in the intimacies of lovers than in the world at large.

Perhaps understanding that he faces a significant hurdle—I defy you not to picture bland stud Armie Hammer and emo twink Timothée Chalamet as you read—Aciman focuses on Sami, Elio’s father. As the book opens, the man, now quite amicably divorced from Elio’s mother, is on a train bound for Rome, fretting over whether to flirt with Miranda, a much younger woman sharing his compartment. He does, and the two have the kind of unreal conversation people have in independent films. Sami’s off to see his son, but when Elio cancels, Miranda insists he join her and her elderly father for lunch.

Aciman is skillful at cataloguing the sensual pleasures of a bourgeois existence: artistically inclined people moving through flawlessly appointed villas. In his world, food, music, art, poetry, sightseeing, and conversation are a matter of seduction: “She split open the branzini she had broiled in a cast-iron frying pan, removed their bones, and on a different plate came the spinach and old puntarelle, over which, once we were seated, she sprinkled oil and freshly grated parmesan.”

After lunch, Sami pulls some strings so that he and Miranda might visit a private museum. “You fed me fish and walnuts, and you love statues, so I’ll show you the most beautiful bas-relief you’ll see in your life. It’s of Antinoüs, Emperor Hadrian’s lover. Then I’ll show you my favorite—a statue of Apollo killing a lizard, attributed to Praxiteles, possibly the greatest sculptor of all time.” You’ll be forgiven if this bit of dialogue makes you lose your puntarelle.

They spend that night together, and it’s not unsexy. But an older man falling for a younger woman is a familiar tune. I don’t think gay sex is more inherently transgressive, but it is more surprising when treated as poetic yet still frank, as it was in Call Me by Your Name. Still, if you think it’s hot when people talk about Cavafy, or Dostoyevsky, or Haydn, or Brassaï, you’ll be undone by Find Me.

Elio is given almost as many pages of the book as his father, but he feels like a more minor character in this novel than its predecessor—more vague and also more milquetoast. Now a professional pianist, Elio meets Michel, whose charms eluded me, during the intermission of a chamber music concert. We get another slow pas de deux: expensive meals, sips of calvados, heady conversation. As the two shower together, Elio thinks, “I felt like a toddler being washed and dried by his parent, which also took me back to my very earliest childhood when my father would shower with me in his arms.” (Gross.)

Michel is older than Elio; Sami is older than Miranda. Aciman clearly wants us to make something of this, but what, I have no idea. Call Me by Your Name has a kind of infectious horniness its sequel lacks. By the time Miranda’s confessed her incestuous desire for her brother—“I wanted him to make love to me, not just fuck me, because it would have been the most natural thing between us, and perhaps this is what lovemaking is”—I was ready to take a lifelong vow of chastity.

A work of art remains static. We’re the ones who change. I can understand why an artist might return to his most successful work, but you can’t go home again—even if that home happens to be a flawlessly appointed villa.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novels Rich and Pretty (2016) and That Kind of Mother (2018; both Ecco).