We name things to make them less fearful. It’s an expression of affection or conquest (isn’t that why Adam christened the animals?). I think of how my kids sometimes bark out “Alexa, play Mamma Mia!” even though we don’t own an Amazon device. I’ll never buy one of those things, but my resistance is futile: My children already inhabit a reality in which they’re on a first-name basis with the internet. It’s like no one remembers HAL!

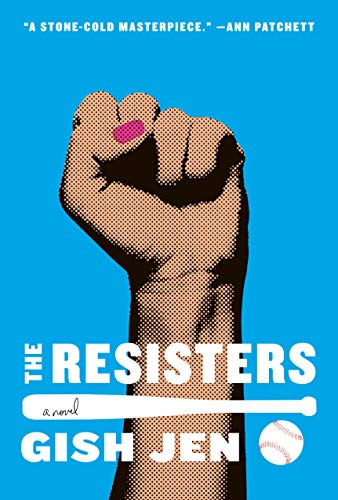

The Resisters, Gish Jen’s fifth novel, posits a future perhaps less distant than we think. Forget first names; the tech infrastructure that undergirds all of society, known as the Autonet, has been dubbed “Aunt Nettie.” The diminutive suffix and respectful title say it all; we’ve built the machine, so we feel we understand it and hope it might in turn feel some kinship with us. In her novel Future Home of the Living God, Louise Erdrich called the internet “Mother.” And as we well know, family can fuck you up.

Aunt Nettie is ever present. During an argument, she might chime in with pablum: “Life is hard. You never know who you can trust. Life is not fair. People are cruel because they don’t know how to be kind.” Imagine if, instead of your scrolling past inspirational memes, they were spoken to you by your living room. It’s a nightmare scenario. Readers understand dystopian fiction’s conventions enough to know from the outset that Aunt Nettie doesn’t really want to help.

In The Resisters’ horrific techno-future the United States is known as AutoAmerica, and global politics mirrors corporate consolidation: West Africa, Greater Cuba, ChinRussia, the Saudi Sphere, AustraliaZealand, and the European Union (the familiar lends some verisimilitude to the whole enterprise). The concept of nation has endured but borders are considered impassable, and AutoAmerica has repatriated some percentage of its populace under a policy called “Ship’EmBack.”

Those who remain fall into two classes—the Netted (an eloquent coinage for an elite nestled in the bosom of Aunt Nettie) and the Surplus, a category that encompasses the majority: “Factory workers, drivers, and customer service representatives, in the beginning—joined, as Aunt Nettie evolved from tool to aide to master by assorted doctors, lawyers, teachers, accountants. Professors. Programmers. Brokers. And, as Aunt Nettie assumed an ever greater role in government: Staffers. Poll workers. Selectmen. Auditors. Ombudsmen. Judges.” Surplus is an effective term as well; a civilization in which judges and educators are extraneous is no longer human.

So what’s the point of being alive? It’s hard to answer. The Surplus survive on a basic income (Jen never tells us the year, but presumably it’s after an Andrew Yang presidency). They earn “Living Points” by consuming the food and other products created by Aunt Nettie. But who’s in charge here: the Netted or the Net? One character reasons it out with us:

Like when Facebook became a utility and gave all that data to Aunt Nettie? That’s where all those DelectableElectables came from. Those perfect candidates they learned to design. . . . Candidates who sure enough got voted in and then approved expanding the Autonet. . . . It’s like the Autonet gets voters to vote for itself. And who knows if the Autonet’s taken everything over at this point or if there are even people behind it.

The dispossessed live adrift on the rising seas. Snow is almost unheard of. Frogs and honeybees have gone extinct. Does it matter who’s calling the shots?

Our narrator, never named, is a Surplus, a former professor. His wife is Eleanor, an attorney and outspoken critic of the government, or Aunt Nettie—one and the same, really. Their family lives in relative comfort (that is to say: on land) but under the ever-present threat that Eleanor’s activism might lead to their being Cast Off. It’s happened to their friends: “set to drift on the high seas, with every harbor closed against them.” At any moment, a government strongman (“Special Enforcer”) might come calling; there are vigilant drones overhead. Our narrator tinkers in his basement workshop to come up with devices to outsmart the bugs the house uses to listen to its inhabitants.

The couple have a daughter, Gwen—the narrator speaks of the nation’s “One Chance Policy,” an echo of contemporary China—who is a savant at baseball, a natural born pitcher, long-armed, strong, only a toddler when she starts hurling her plush animals from the crib. Gwen’s parents organize an informal league for some of the Surplus children. It’s covert, because it must be, but somehow thrives. Our narrator sees in this bit of luck, as in everything in life, the invisible hand of the state: “Maybe Aunt Nettie had realized that baseball—Unlawful Assembly or not—kept us out of trouble.”

Some of the liveliest writing in The Resisters is about baseball:

That first inning, the Jets’ first baseman did still hit a line drive into left field for a base hit; their catcher hopped a ball right past our shortstop, too, putting a second runner on base. And after them came the Jets’ shaggy second and third basemen, Gunnar and Bill Apple—identical twins who had been normal-sized kindergarteners back when they were classmates of Gwen’s, but had since grown to be big as bison. They looked as though they belonged on a prairie, not a field.

Jen writes electric, entertaining sentences. I can hear the author having fun here and throughout the book. It’s baseball that gives The Resisters its shape, and this is effective even if you, as I, hate baseball. In sport, Jen finds a metaphor for what it is to be human: Gwen’s is a natural ability in a world of artifice and technological enhancement. Sports are unpredictable as well as pointless. We are not alive if we only consume and earn. To be a person is to play.

Works that posit an alternate world have to expend some energy on establishing that reality’s texture. Jen relishes world building maybe too much. People stay in touch via FriendGrams and 3-D HoloPix; they get around via SkyCar; they use GenetImprovement to gain superhuman powers, or PermaDerm to drain the pigment from their skin. These branded coinages pile up, then begin to grate. Authors possess authority, and Jen squanders hers on set dressing when she might simply establish the world’s contours and let the reader do the rest.

There’s some telling critique in Jen’s language. The Netted are “flaxenflair,” and you can hear beneath that euphony the menace of white power. The Surplus, by contrast, are “coppertoned,” a flourish that cleverly recalls the familiar consumer product. The narrator and his wife are black and Asian, respectively, but in a way this felt beside the point. The society is inhumane; of course it’s also racist.

I fidgeted during this exposition, ready for the story. The unnamed narrator is tasked with all this authorial explaining, and it makes him a tiresome companion. He is our Sherpa, but ends up feeling like a know-it-all. And while maybe it makes sense that the introductory pages would need to tell us how to read the book, the third of the book’s four sections lays bare the flaw in the overall design.

The all-seeing Aunt Nettie inevitably discovers that Gwen is a gifted athlete, and she’s recruited to Net U, the finishing school for the elite. There’s a process called Crossing Over by which the Surplus can shed their outsider status, and by proving herself at Net U and joining the AutoAmerica Olympic team, Gwen might be able to change who she is and ensure her entire family’s salvation.

When Gwen accepts the invitation to Net U, her father cannot tag along. To keep him a viable narrator, Jen has father and daughter communicate via messenger pigeon—an analog workaround to Aunt Nettie’s prying eyes. Perhaps predictably, the epistolary mode is not as effective as the direct storytelling. Even beyond the matter of their awkward written communiqués, it makes little sense that Gwen is our hero but only ever seen through her father’s eyes.

Gwen faces a moral choice: play the game she loves for a country that hates her, or renounce the comforts of being Netted to underscore how arbitrarily those are awarded to a fortunate few. This is the heart of the book, but it is relayed to the reader almost as a play-by-play and feels more distant than it should. We cannot truly see our hero, our view always through a father’s loving eyes.

This third section seems to promise a confrontation between Gwen and her new, Netted peers: the clashing of these two worlds. I was disappointed to see the story devolve into a hackneyed and uninteresting romance when Gwen takes up with her baseball coach. I wondered whether, having spent all that imagination on the book’s setup, the author wasn’t sure what to do.

The novel builds to (what else?) a big game. We’re engaged by what’s happening on the field, even if we’re aware that it’s also mostly a metaphor. The Resisters’ final section shows that Jen is a canny architect, the story more carefully crafted than it might seem. Details from the novel’s early pages become newly resonant in this last inning—perhaps my fault, but I had trouble recalling them, and never felt the epiphany the author was reaching for.

Does any reader still have the desire—let alone the wherewithal—for the novel of dystopia? Right this very moment, Venice is washing away and madmen run even our democracies. These are times beyond satire; aren’t we all just waiting for the Trump administration to propose eating Irish children? Dystopian fiction wants us to peer into a kaleidoscope that gradually reveals itself to be a mirror. Lovely as Jen’s writing is, I never felt indicted or even discomfited by the book. Maybe I’ve just lost my ability to feel shocked. A story of the haves and the have-nots? Tell me something I don’t know.

Rumaan Alam is the author of Rich and Pretty (2016) and That Kind of Mother (2018; both Ecco). His new novel will be published in October.