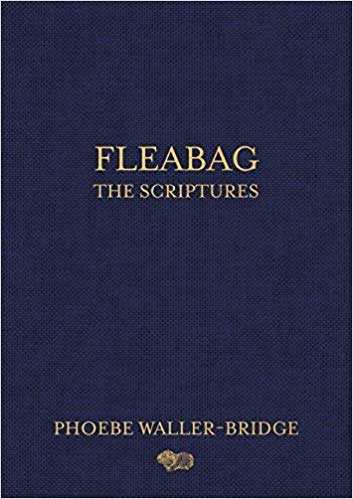

The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold serif letters like a Gideon Bible—have become a new kind of religious text, albeit one that preaches primarily to secular women living in major metropolitan areas. And there is some truth to this visual provocation: If anyone had a truly blessed year, it was Phoebe Waller-Bridge. A picture of her lounging at the Chateau Marmont after she swept the Emmy Awards in September, with a vodka gimlet in one manicured hand and a cigarette in the other, went viral overnight. Women set it as their phone lock screens and desktop backgrounds; they meditated on it like a rosary. It’s so victorious, so insouciant. Here was a woman not ground to a pulp by anger at the news cycle, but wringing the juice out of life. She appears to be luxuriating, a hard-earned repose after several years of grinding out scripts. And on the seventh day, Phoebe Waller-Bridge rested.

Her rapid rise, as idiosyncratic as it is, has already become mythologized. Her story of writing and starring in her own best material gives faith to the faithless scribblers, hope to the hopeless actors: If you are witty enough, brash enough, unbridled enough, canny enough with a pen, you too might be able to convert your anxieties into a scrappy one-woman play that premieres at a fringe festival and then becomes a global phenomenon. But Waller-Bridge’s blazing path is less of an it-could-happen-to-you fairy tale than a very specific and singular chain of events. To begin with, there is the matter of Waller-Bridge’s upbringing, in Ealing, London, where her father launched a high-tech stock-trading platform and enabled his three children to pursue lives in the arts (Phoebe’s brother, Jasper, is a creative director; her sister, Isobel, is a composer who wrote the scores for Fleabag, an episode of Black Mirror, and an upcoming film adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma). Waller-Bridge attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, the storied training ground of Ralph Fiennes, Kenneth Branagh, Glenda Jackson, Alan Rickman, Ian McShane, and Diana Rigg. The school takes fewer than thirty students in any given year. To note this polished pedigree is not to downplay Waller-Bridge’s accomplishments. It is simply worth saying that Waller-Bridge’s many talents were honed, and that she was entrepreneurial about honing them. Somewhere along the way, she seems to have developed an astute gauge for whatever thing will launch her into the next—bigger—thing. Fleabag, the character, is totally hapless, but Waller-Bridge is canonically capable.

After graduating from drama school in 2006, she writes in the afterword to The Scriptures, she had “no job and little confidence,” so she and a friend (the director and dramaturge Vicky Jones) started their own theater company, DryWrite, where they would challenge each other to write monologues to perform at a monthly gathering at an East London pub. She spent half a decade taking small parts on British television (she’s in Bad Education and Broadchurch) and developing her own material. And then something hit: In 2012, Waller-Bridge performed one of her monologues—the seed that would grow into Fleabag—at the London Storytelling Festival at the Leicester Square Theatre, and it got such a rousing response that a producer immediately booked her into her own space at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Waller-Bridge raised four thousand pounds on Kickstarter for the Fringe—mostly to pay for design and staging, as she was the only cast member—and it immediately paid off. The expanded version sold out and became a critical darling, and suddenly every television executive in town (and some overseas) wanted a piece of it. While Waller-Bridge worked on an adaptation for the BBC, she also wrote six episodes of a comedy called Crashing, about a group of twentysomethings living in an abandoned hospital, sold it to Channel 4, and played the lead role herself. The show debuted in January of 2016, and Fleabag aired later that same year. Waller-Bridge was thirty-one years old.

Waller-Bridge broke out precisely because she was no longer an ingenue. From the first moments of Fleabag, when we see Fleabag (the only name her character ever gets) standing inside her front door, her makeup smeared and her hair askew, preparing to receive a gentleman caller at two in the morning, we get the sense that this is a woman who has been places, who has done things, who has earned her nihilistic sublimation into snogging and sardonicism. By the end of the first season we learn that she’s not just a reckless person, she might be a bad person, or at least a person in so much pain that it radiates into the lives of those around her. This darkness was part of the instant appeal of Fleabag—Waller-Bridge was not just exploring an antiheroine, she was exploring how far she could push a character into cruelty and self-destruction and still find, if not redemption, then peace. Her technique of speaking directly to the camera in the middle of a scene is familiar, but also frantic—Fleabag is practically pleading with the audience, begging us to witness her ghastliness. She’s simultaneously asking for absolution and for someone to smite her, which is why it is appropriate that the second season was all about God.

My guess is that many people who buy The Scriptures will turn immediately to the scene on pages 338 to 340, in which Fleabag visits the Hot Priest (or Priest, as he is known in the script) at his parish and sits inside a confessional. She starts to tally up her sins: “There’s been much masturbation. A bit of violence and then of course the endless fucking blasphemy.”

But the heart of the scene comes when the priest asks her to describe what she wants, even if it is wicked. She replies:

I want someone to tell me what to wear every morning . . . I want someone to tell me what to eat, what to like, what to hate, what to rage about, what to listen to, what band to like, what to buy tickets for, what to joke about, what not to joke about. I want someone to tell me what to believe in, who to vote for, who to love and how to . . . tell them. I just think I want someone to tell me how to live my life, Father, because so far, I think I’ve been getting it wrong.

The priest then tells her to kneel—it’s more erotic than ecclesiastical—and kisses her. As Waller-Bridge writes of this moment in the script, “It’s a gentle, loving kiss. It’s nothing short of fucking beautiful.”

This scene contains all the elements that make Fleabag work—the tension between holiness and horniness, the unrequitable love between two lonely human beings that serves as a metaphor for the unbridgeable distances between all people, for the millennial angst that comes with navigating an increasingly baffling world without even knowing what band to like. But it also works because of Waller-Bridge’s delivery; her steeliness slips, for a moment, and she’s exposed. Waller-Bridge performs brokenness in Fleabag, which is notable not only because she fully sells it on screen, but also because, upon reading The Scriptures, you see just how finely calibrated her writing really is. The pleasure in reading The Scriptures, beyond the delight of seeing how a script comes together, is in realizing that Waller-Bridge’s literary ambitions are grand. The scenes unfold like chapters of a novel. Symbolism stretches over several pages; totems (like a voluptuous statue that Fleabag keeps stealing from her monstrous stepmother) disappear and reappear. Jokes land in the middle of monologues with a satisfying fizz. She sets up surprises that she titrates out slowly over several episodes, until the reveal is as devastating as possible.

Waller-Bridge is not like you or me—she has been gunning for this moment for a decade, chugging headlong toward it—and that is what makes her glamorous and a bit ethereal. She’s working so hard and never disguises the effort. But she also cuts such a sleek profile that you almost forget the hustle. In the Fleabag finale, Fleabag says goodbye to the priest, then disappears into the London night, leaving the camera’s gaze behind her. Where she is going, no one else can follow. She leaves the viewer unsatisfied, searching for meaning in the darkness. In The Scriptures, Waller-Bridge offers a few answers, but she still keeps much to herself. It’s a bit maddening, a bit mystical. But it just might make you a believer.

Rachel Syme is a writer in New York and a frequent contributor to Bookforum.