“I do not believe in serendipity,” says Percy, the narrator of Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s The Exhibition of Persephone Q. “I don’t think there are moments, of which so many people speak, in which a life irrevocably and neatly forks, like a line in your palm. I believe instead that the past returns to you in waves, crashing onto the shore, so that the ground on which you stand is always shifting, like a beach, imperceptibly renewed.” I found myself returning to this passage throughout my reading, and for some days afterward, trying to decide whether I believed it, either as a general proposition or with regard to this story in particular. I’m still not sure, and what’s more, I’m not sure that she’s sure. But such uncertainty feels appropriate for a novel whose central subjects are ambivalence, mystery, memory, and absence; a novel that makes for propulsive reading despite having relatively little forward motion, its plot tending less to arc than—pace critic Jane Alison—to meander and spiral, then explode.

When we first meet her, Percy is in bed watching her husband sleep. (Percy, by the way, is short for Persephone, itself a pseudonym borrowed from an art show, about which more in a bit.) As though under the spell of some entry-level imp of the perverse, she briefly pinches his nose closed. Alarmed by her own action, she begins to take nightly walks whose nominal purpose—to prevent her from potentially suffocating her husband—is clearly superseded by their narrative function, which is to give Percy time to fill us in on her circumstances and to allow Stevens to delay the novel’s actual inciting incident for nearly forty pages.

It’s the winter after 9/11, and Manhattan is still wary and fragile. “I was suspicious of anyone who still claimed a stake in normal,” Percy says, recalling how in October “trees released poisoned leaves to the green, a light northward breeze perfumed the air with drywall dust and soot.” Also, she is pregnant and has not told her husband, though she knows he’ll be happy about it and she has every intention of keeping the baby, never mind her concerns about impending motherhood. This is the novel’s meandering part, but Stevens’s vivid, swerving sentences stage bracing dramas of their own.

I remember one morning, in late July, I watched a woman spill a drop of coffee on her cream-colored blouse. She looked down at the modest stain, the light changed. She pulled the silk away from her body and poured the remainder down the ruffled bib. Later, I looked into the air shaft outside our window and found a deposit of paper cranes; they gathered against the brick like bright and fallen leaves and were soon pulverized by rain.

For some writers, a terrorist attack and an unplanned pregnancy would be enough narrative fodder for a spare, lyrical novel composed largely of interiority. Not for Stevens, who packs in a crash course in art history; asides about the early internet’s false promises of freedom and anonymity; a New York coming-of-age story; and a supporting cast that includes a self-help author, a psychic, and a neighbor who disappears. Unsurprisingly, keeping all these people occupied leads to a couple of cul-de-sac subplots and some surfeits of quirk. But I admire that Stevens is willing to take risks, and—crucially—all her highest-stakes gambles pay off. I am therefore as disinclined to dwell on this sly and beguiling novel’s minor flaws as I am to give away too much about how its simmer finally comes to boil.

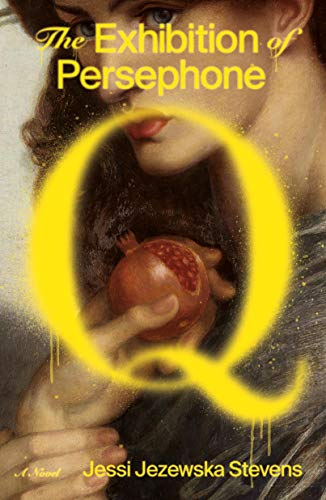

But about that inciting incident. Percy receives a package containing the catalogue for an art show called “The Exhibition of Persephone Q,” which features a series of digitally manipulated versions of the same photograph of a nude woman asleep in her bedroom, her body exposed but her face turned away from the camera. The manipulations are of the Manhattan skyline visible through the woman’s outer-borough window. “In these photographs,” the catalogue explains, “the disappearance of major landmarks, including the Chrysler and Empire State buildings, and, most notably, the towers, challenges received ideas about America’s most recognizable skyline.”

The skyline isn’t all Percy recognizes. The photographer is an ex from a decade ago, when she was in her early twenties (he was older), and the bedroom and the nude woman evince an eerie, icky familiarity. She sets out to prove herself right—and wronged. She emails the ex, who denies that it’s her in the photo. Her friends are sympathetic but unable to confirm what Percy suspects she sees. They want to believe her, but the bedroom is relatively indistinct and so is the body: white, conventionally attractive, unblemished, faceless. “I tried to greet it as a stranger might,” Percy says at one point. “This could be any woman on the bed, in any woman’s room. She was a site of exegesis, as anonymous as ruins.” And yet, “I was not crazy. I was certain. Though I suppose self-assurance was no defense. In fact, it strengthened the charge.” But if Percy’s immediate concern is confirming her presence in the photograph, there’s a deeper question lurking about her relationship to the person—to the body—on the gallery wall.

Documentation took on new meaning for me. My breasts were strange. My ankles swelled. . . . Soon I’d stretch around four, six, nine months of life, and then I really wouldn’t be the same. . . . This fate unfurled itself like a red carpet through the center aisle of my mind. I felt as though I might as well insist on my existential imprint while I still could.

A question about who you will become is always a question about who you have been, and any given present-tense “self” is little more than the narrow bridge connecting the past and future: a contingent truth suspended between two fictions. The Exhibition of Persephone Q is a resonant and uncanny novel, a moving meditation on “how casually one version of reality detaches from the truth; it peels away naturally, like damp wallpaper in a neglected room.” Jessi Jezewska Stevens is a promising, persuasive new writer, and I will be surprised if this doesn’t turn out to be one of the strongest debut novels of 2020.

Justin Taylor’s memoir Riding with the Ghost will be published by Random House in July.