Jenny Offill’s first novel, Last Things, was narrated by an eight-year-old girl named Grace. Grace’s mother, Anna, starts out a little crazy, the kind of intellectual eccentric whose home-school curriculum consists of a room painted black and a “cosmic calendar” marking out the origins of life, and then she gets a lot crazy—driving naked, insisting on picnicking inside a burned-down restaurant, that kind of thing. On Anna’s thirty-fifth birthday, mother and daughter bury a time capsule filled with photographs. “The box was made out of a special kind of metal that could survive any kind of disaster known to man,” Grace explains. “It could survive a terrible fire or an earthquake or another age of ice.” Anna has told Grace that whoever finds the photographs won’t understand them, because in the future, “no one will get married or swim in the ocean anymore. . . . We’ll all live in huge buildings connected to one another by tunnels.” Still, theirs is an unmistakable act of faith in posterity, the possibility of being found. “Someday, a thousand years from now, someone would dig it up and know that we were here.”

Last Things was published in 1999. Twenty years later, what seems crazy is not the suggestion that future people will eschew marriage or that the ocean will be an uninviting place for a dip—it’s the very idea of a time capsule itself. No one in Offill’s new novel, Weather, would dream of burying such a thing. It wouldn’t matter what kind of metal the box was made of, unless the metal was magic. We no longer feel confident that conscious creatures with opposable thumbs will be walking the earth in another thousand years. We’re not sure about the next hundred.

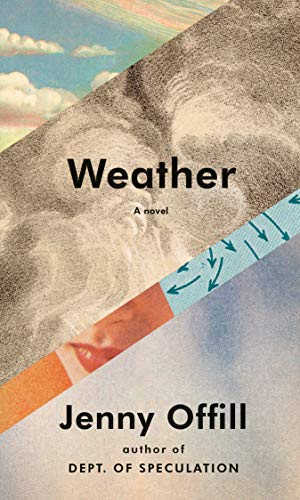

Weather brings together two disasters—the decades-long accumulation of environmental destruction that now has us careening toward “climate departure,” and the 2016 election. “There is a period after every disaster in which people wander around trying to figure out if it is truly a disaster,” Offill writes. “Disaster psychologists use the term ‘milling’ to describe most people’s default actions when they find themselves in a frightening new situation.” The idea of “milling” could also apply to the book’s shape. Like Offill’s last novel, Dept. of Speculation, which New Yorker critic James Wood described as “a stream of interruptions,” Weather unfolds, or stutters, as a series of fragments, some as long as a page and others as brief as a sentence; some are epigrams, some are jokes, some are fully conceived miniature scenes.

Lizzie is a librarian at the university where she failed to complete her dissertation on “The Domestication of Death: Cross-Cultural Mythologies.” She lives in Brooklyn with classicist husband Ben, who, after two bad years on the job market, became a designer of educational video games. Around the house he’s given to sardonic jokes: When Lizzie doesn’t unpack her suitcase after a trip, he asks, charmingly, “Are you trying to tell me something?” Ben is also the kind of guy who takes the long view of things, who uses history to fend off the disturbing present. “People always talk about email and phones and how they alienate us from one another, but these sorts of fears about technology have always been with us,” he says, accurately and unhelpfully, as if knowing that the fear has a history makes the technology less alienating.

Where Dept. of Speculation was condensed and quick, moving tensely like a projectile, Weather meanders, a bit panicky, around its situation. When Lizzie’s former dissertation adviser, who hosts a podcast about climate crisis called Hell and High Water, offers her a job responding to listener emails, Lizzie goes from anxious to obsessed with disaster preparedness. She’s also preoccupied with her brother Henry, a recovering addict. During the course of Weather Henry marries and fathers a child with an advertising executive; after a relapse, the marriage falls apart and he moves in with Lizzie. Henry’s a worrier. He worries that he will not be able to travel thirty-four miles with his daughter on his back, like a refugee in the news did. Then he worries that his failures to protect will be more overt—that he will leave the baby in a hot car where she will suffocate, that kind of thing. Lizzie takes him to see her meditation teacher. The teacher asks Henry to write out what he has been thinking about. “It’s unbearable,” Henry says of the assignment. “It’s barely bearable,” the teacher corrects him. Whereas in Dept. of Speculation the marriage was threatened by a cheating husband, in Weather it’s Lizzie whose eye wanders, to a handsome war correspondent she meets on a bus. It’s easy to understand the attraction. He at least gets the feeling of impending collapse.

The “weather” of the title, of course, is this climate of feeling, a pervasive, barely bearable anxiety that moves inside and outside the family and gives the novel a diffuse quality. The title notwithstanding, Dept. of Speculation was about the intrusion of reality: a new baby, an affair. Weather is a more slippery book because it’s about fantasies: fantasies of destruction and romance and salvation. Lizzie does not experience a flood or fire. She isn’t a refugee; she reads about them on the internet. Of course she flirts with the war correspondent and doesn’t sleep with him. Of course her brother worries about committing an act of violence and never does. The book is about thinking and feeling rather than doing, about inaction and the fear of action. Like Dept. of Speculation, it valorizes what is known over what is new. But its temporality is impending. The only big thing Lizzie manages to do is go to the dentist. Even that is a half action: She comes home with a night guard, and then doesn’t wear it.

If that sounds like a criticism, it isn’t; Weather captures something essential about a contemporary mood, a kind of pre-traumatic stress caused by the threat of what we know and don’t do anything about. Other things Lizzie knows: how to make a fire out of a tin of tuna fish. How to catch a fish in your shirt. That you should always carry chewing gum (“it suppresses the appetite and you can supposedly fish with it, but only if it is a bright color and has sugar”), and that red ants have “a lemony taste.” As a novelist, Offill has always been drawn to fun facts—Last Things contained information on birds and the cosmos, and Dept. of Speculation used space exploration as a way to talk about loneliness—though the facts in Weather have a less playful edge to them. It is worth noting that this is Offill’s first novel that does not use outer space as a motif. What good is outer space to us now?

Weather occasionally overrelies on zingers, and there’s a silly running gag about an unreliable car service run by someone named Mr. Jimmy. But Lizzie’s ongoing drama with other parents and the neighbors, especially the unpleasant Mrs. Kovinski, is apt. We think of climate dystopia as being the province of science fiction, but it can and should be rendered in a recognizable milieu. Living through ecological meltdown will also be just living—hating the neighbors, having awkward interactions with the other parents at school.

In another book, the character of Henry would be an obvious metaphor for the environment, careening toward ruin as Lizzie tries to “stabilize” him, but in Weather he’s simply one of a number of ambivalent attachments. No matter how the world ends, we will continue to be human beings until we are dead.

The knowledge that Lizzie amasses is of limited value. “Then one day I have to run to catch a bus. I am so out of breath when I get there that I know in a flash all my preparations for the apocalypse are doomed. I will die early and ignobly.” Lines like these come off a bit like someone bombing at a comedy club, but they are also plausibly in character. Ben returns from the “glamping” trip he has taken their son on, and in the intervening time has “done the math” on the crisis. He hangs something new above his desk, a quote from Epictetus: “You are not some disinterested bystander / Exert yourself.” He helps Lizzie make a list of “requirements for our doomstead: arable land, a water source, access to a train line, high on a hill.” This collaborative imagining is the most romantic gesture of the novel.

There is something unsatisfying about Weather. It looks at the scariest things, but as if with one eye only. Offill’s mordancy is a kind of shield, as is the truncated form of the narrative fragments, which sometimes tie up feelings rather than allowing them to accumulate or overwhelm. It’s like the book itself can only barely bear its subject. Yet why should we ask one book to do what none of us can? It’s a novel for today, as novels today must be. To the list of everything that climate crisis has taken and will take away we can add the very notion of posterity. Whatever we do now—whatever we write, make, or build—has to mean something now, to the people who are here. Weather begins with a quote from a town meeting in Milford, Connecticut, in 1640: “Voted, that the earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof; voted, that the earth is given to the Saints; voted, that we are the Saints.” The Puritans not only believed that they were acting to ensure an eternal reward in Heaven. They believed they could create a Heaven on Earth, feel the presence of God in this life. Those of us who believe that we can salvage at least some habitable community out of the hellish destruction around us would do well to work quickly and together and with as much attention to the present as to the future. Or as Lizzie puts it: “The core delusion is that I am here and you are there.”

Christine Smallwood’s debut novel will be published by Hogarth.