Across several decades of her career, Helen Frankenthaler painted an intimate, interior sense of landscape. She achieved this, in part, with a technique called “soak stain,” which she invented while creating her earliest masterwork, Mountains and Sea, 1952. Frankenthaler would pour paint diluted with turpentine onto unprimed canvas, creating watercolor-like effects. The softened hues and diffuse shapes captured the subjective experience of the natural world. While watercolors are typically small, Frankenthaler preferred large canvases, sometimes as wide as twelve feet. The scale and the method harked back to J. M. W. Turner’s gauzy Venetian skies and waterways.

Frankenthaler’s rendering of landscape as a palpably involving experience is on ample display in these two catalogues from recent exhibitions at the Venice Biennale and in Rome. Pittura / Panorama features several lush, immersive works like Riverhead, 1963, in which a great swath of variegated blue washes over earthen bands of green and brown. The areas of color seem to move both within themselves and against one another and give the volatile impression of chemical reactions. Painted nearly thirty years later, in 1990, Frankenthaler’s Snow Basin presents a geometrically organized yet paradoxically free-flowing scene—chaotic brushstrokes constitute a block of white that appears to spill its turbulent contents across the canvas. Pale horizontal bands of blue, orange, pink, and gray undergird the heavily textured blizzard bursting from that angular source. The contesting forces meet in a pink-encircled swirl of white near the painting’s center—the eye of the storm.

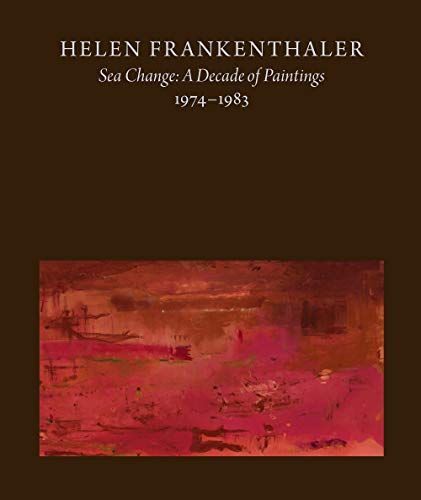

Sea Change: A Decade of Paintings also showcases Frankenthaler’s ability to charge color with momentum and infuse landscape with emotional reverberation. Despite its title, Eastern Light, 1982, stints on illumination. Several bright but meager squalls of white paint erupt amid the shadowy depths. Draped around the perimeter of a vibrant maroon field—one animated with what could be approaching daybreak—are gloomy sheets of black. The morning’s first light must press past these barriers; the thickly brushed splatters of white are harbingers of that coming hour. From that same year, Tumbleweed offers respite from such ominous moods—dashes of blue, black, and red paint skitter across a lustrous green background, creating a playful commotion. Accompanying the nearly audible wind moving through the grass is the mild alarm the viewer feels as the splashes of color hurtle past. Frankenthaler’s landscapes register inwardly, even as their energy envelops the viewer.